Greenbackism in Alabama

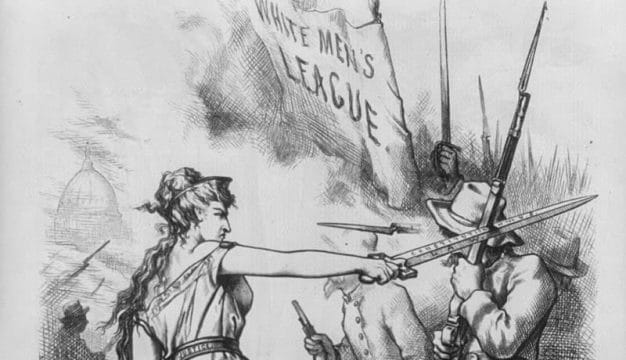

The Greenback movement, also referred to as Greenbackism, was a short-lived coalition of farmers and laborers that arose in the mid-1870s to protest a variety of federal monetary policies. The movement made allies with organized labor and died out in the early 1880s but managed to influence the Populist movement later in the nineteenth century. In Alabama, the Greenback movement foreshadowed the efforts of the Populists at building a biracial coalition of farmers and industrial workers.

The movement took its name from its support for the continued minting of paper money. The national Greenback-Labor Party (GLP) platform of 1878 demanded that the federal government issue an adequate supply of paper money at a time when the currency supply was failing to keep up with population growth. Many southerners believed that federal monetary policies were particularly detrimental to their region, which suffered more than others from a lack of currency and credit, and overly advantageous to the Northeast, which was then the nation’s center of industry and finance.

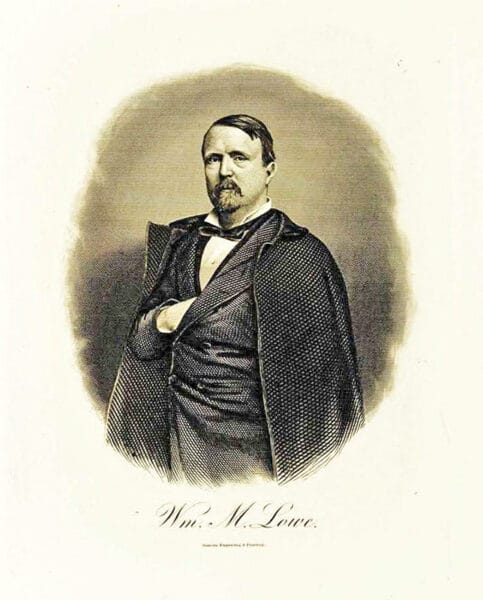

Lowe, William

In Alabama, the Greenback movement drew support from a disparate coalition of farmers and laborers, both white and black, and under the guise of the GLP, served as the chief vehicle for opposing the dominant Democratic Party from 1878 to 1882. It came together when coal miners in the Birmingham district began forming Greenback clubs, which served as local party chapters, in 1877. By August 1878, 12 of these clubs existed in Jefferson County, where two GLP candidates made respectable though unsuccessful bids for the state legislature that year. The GLP fared better in the state’s Tennessee Valley, where its candidate, William M. Lowe, won election to the U.S. House of Representatives in November 1878. In this largely rural portion of the state, the party showed more concern with longstanding political disputes than with its national focus on the currency issue.

Lowe, William

In Alabama, the Greenback movement drew support from a disparate coalition of farmers and laborers, both white and black, and under the guise of the GLP, served as the chief vehicle for opposing the dominant Democratic Party from 1878 to 1882. It came together when coal miners in the Birmingham district began forming Greenback clubs, which served as local party chapters, in 1877. By August 1878, 12 of these clubs existed in Jefferson County, where two GLP candidates made respectable though unsuccessful bids for the state legislature that year. The GLP fared better in the state’s Tennessee Valley, where its candidate, William M. Lowe, won election to the U.S. House of Representatives in November 1878. In this largely rural portion of the state, the party showed more concern with longstanding political disputes than with its national focus on the currency issue.

In Alabama, as in several northern states, the GLP became closely associated with the Knights of Labor, a labor and reform organization that recruited workers and farmers, both white and black, regardless of economic status, skill level, or gender. This connection with the Knights and the major role played by miners in the Alabama GLP resulted in the party adding a plank to its state platform in 1880 demanding the repeal of the convict-lease system. The GLP ran its first gubernatorial candidate that year, James Madison Pickens of Lawrence County, a Confederate veteran, Disciples of Christ preacher, publisher of religious journals, farmer, and educator who was sympathetic to the plight of the working classes.

Pickens won the endorsement of the state’s Republican Party in the 1880 election but still received only 24 percent of the vote as the sole challenger to Democratic incumbent Rufus W. Cobb. The Democrats’ use of violence, intimidation, and tampering with vote counts undoubtedly played a large role in Pickens’s poor showing. Such tactics also initially deprived Lowe of reelection to Congress, but he contested the election results and was ultimately declared the winner by the U.S. House of Representatives. Neither party leader lived much longer. An assassin, apparently motivated by politics, killed Pickens in February 1881. Lowe died in October 1882, depriving the Alabama GLP of its lone major officeholder.

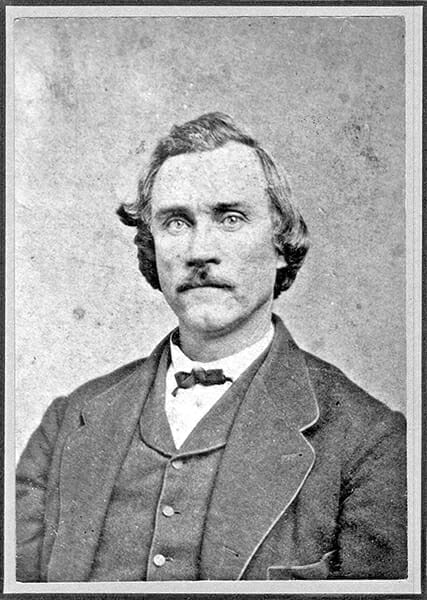

James L. Sheffield

Despite these setbacks, the GLP ran its strongest campaigns in Alabama in 1882. Although Democrats swept the state’s congressional elections, GLP nominee James L. Sheffield of Marshall County made the best showing by any non-Democratic gubernatorial candidate in Alabama between 1876 and 1892. Sheffield officially received 31 percent of the votes cast in a two-man contest, but his supporters charged that Democrats’ fraudulent manipulation of vote counts, especially in the Black Belt, cost him many votes, a charge with which historians have concurred. GLP and Independent candidates (sometimes scarcely distinguishable in north Alabama) captured 22 seats in the state legislature that year.

James L. Sheffield

Despite these setbacks, the GLP ran its strongest campaigns in Alabama in 1882. Although Democrats swept the state’s congressional elections, GLP nominee James L. Sheffield of Marshall County made the best showing by any non-Democratic gubernatorial candidate in Alabama between 1876 and 1892. Sheffield officially received 31 percent of the votes cast in a two-man contest, but his supporters charged that Democrats’ fraudulent manipulation of vote counts, especially in the Black Belt, cost him many votes, a charge with which historians have concurred. GLP and Independent candidates (sometimes scarcely distinguishable in north Alabama) captured 22 seats in the state legislature that year.

The death of Lowe, the burden of continued defeats by less than democratic means, and the demise of the GLP nationally, however, spelled the end of the Alabama Greenback movement after 1882. By 1884, the state GLP had disappeared. Nevertheless, the Greenback movement in Alabama helped pave the way for the Populist movement of the 1890s. In many of the counties where the GLP had won significant support, the Populists would do likewise as they led a more serious challenge to the dominance of the Democratic Party in Alabama.

Additional Resources

Gutman, Herbert G. “Black Coal Miners and the Greenback-Labor Party in Redeemer Alabama, 1878-1879: The Letters of Warren D. Kelley, Willis Johnson Thomas, ‘Dawson,’ and Others.” Labor History 10 (Summer 1969): 506-35.

Hild, Matthew. Greenbackers, Knights of Labor, and Populists: Farmer-Labor Insurgency in the Late-Nineteenth-Century South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007.

Horton, Paul. “The Assassination of Rev. James Madison Pickens and the Persistence of Anti-Bourbon Activism in North Alabama.” Alabama Review 57 (April 2004): 83-109.

Letwin, Daniel. The Challenge of Interracial Unionism: Alabama Coal Miners, 1878-1921. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Roberts, Frances. “William Manning Lowe and the Greenback Party in Alabama.” Alabama Review 5 (April 1952): 100-21.

Rogers, William Warren. The One-Gallused Rebellion: Agrarianism in Alabama, 1865-1896. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1970.

Webb, Samuel L. Two-Party Politics in the One-Party South: Alabama’s Hill Country, 1874-1920. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1997.