John Basil Turchin

John Basil Turchin

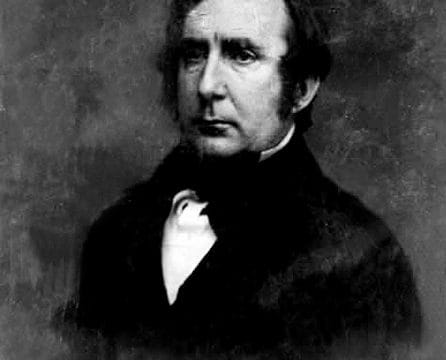

John Basil Turchin (1822-1901) was a U.S. Army officer during the Civil War. He is best remembered for commanding the Eighth Brigade, Third Division, Army of the Ohio that targeted and destroyed civilian property in Athens, Limestone County, on May 2, 1862. The “Sack of Athens” and the Union’s reaction to his subsequent court-martial helped prompt the North’s shift from a policy of conciliation to a policy that punished Confederate civilians who resisted U.S. government objectives or put U.S. soldiers in harm’s way. To southerners, Turchin’s conduct was that of a tyrant waging war on innocent civilians. While many northerners abhorred the Eighth Brigade’s specific actions, they supported Turchin’s desire to punish defiant secessionists.

John Basil Turchin

John Basil Turchin (1822-1901) was a U.S. Army officer during the Civil War. He is best remembered for commanding the Eighth Brigade, Third Division, Army of the Ohio that targeted and destroyed civilian property in Athens, Limestone County, on May 2, 1862. The “Sack of Athens” and the Union’s reaction to his subsequent court-martial helped prompt the North’s shift from a policy of conciliation to a policy that punished Confederate civilians who resisted U.S. government objectives or put U.S. soldiers in harm’s way. To southerners, Turchin’s conduct was that of a tyrant waging war on innocent civilians. While many northerners abhorred the Eighth Brigade’s specific actions, they supported Turchin’s desire to punish defiant secessionists.

Born Ivan Vasilovitch Turchininoff near the Don River in Russia on January 30, 1822, Turchin followed in his father’s footsteps and embarked on a military career. He attended the Nicholas Academy of the General Staff, Russia’s preeminent military school, and after graduation in 1852, was ordered to the staff of the Imperial Guards in St. Petersburg. By the age of 33, he had achieved the rank of colonel. In May 1856, Turchin wed Nadexhda Lvova in Krakow, Poland. A few months later, they immigrated to the United States and Americanized their names to John Basil and Nadine Turchin.

Upon their arrival in America, the couple spent time in New York and Philadelphia. They eventually moved to Chicago when the Illinois Central Railroad hired Turchin as an architect. In June 1861, Turchin resigned from the Illinois Central Railroad and accepted a commission in the U.S. Army at the rank of colonel. Turchin was placed in command of the Nineteenth Illinois Infantry and eventually commanded the entire Eighth Brigade, which comprised the Nineteenth and Twenty-fourth Illinois Volunteer Infantry, Eighteenth Ohio Volunteer Infantry, and the Thirty-seventh Indiana Volunteer Infantry. As part of General Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel’s Third Division, Turchin and his men saw action in Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee before arriving in north Alabama in April 1862.

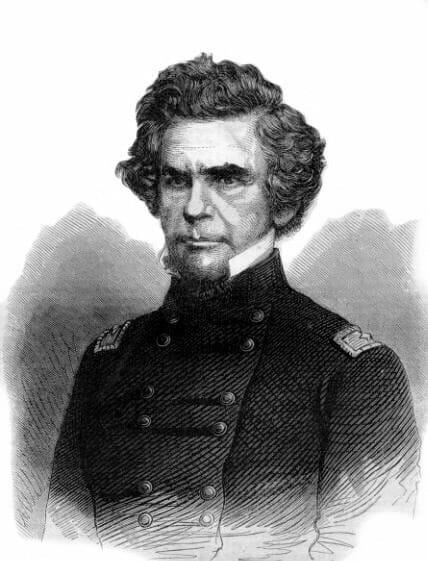

Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel

On April 11, 1862, the Third Division occupied north Alabama along the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. Turchin’s men played a vital role in securing the railroad west of Huntsville and were stationed in the vicinity of Athens and Decatur. A few months before the occupation, Mitchel’s superior, Gen. Don Carlos Buell, had issued General Order 13a, instructing all soldiers from the Army of the Ohio not to threaten, harm, damage, or interfere with civilian property. Neither Mitchel nor Turchin agreed with or abided by Buell’s policy of conciliation. From the moment the occupation began, Alabamians refused to be conciliated and often resorted to burning bridges, firing into federal military trains, and committing a host of other hostile acts to drive out the U.S. forces. With the line between combatant and noncombatant often blurred, Mitchel and Turchin began to hold civilians and towns accountable for their resistance.

Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel

On April 11, 1862, the Third Division occupied north Alabama along the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. Turchin’s men played a vital role in securing the railroad west of Huntsville and were stationed in the vicinity of Athens and Decatur. A few months before the occupation, Mitchel’s superior, Gen. Don Carlos Buell, had issued General Order 13a, instructing all soldiers from the Army of the Ohio not to threaten, harm, damage, or interfere with civilian property. Neither Mitchel nor Turchin agreed with or abided by Buell’s policy of conciliation. From the moment the occupation began, Alabamians refused to be conciliated and often resorted to burning bridges, firing into federal military trains, and committing a host of other hostile acts to drive out the U.S. forces. With the line between combatant and noncombatant often blurred, Mitchel and Turchin began to hold civilians and towns accountable for their resistance.

On the night of May 1 or early on May 2, 1862, Col. J. S. Scott and his Confederate cavalry unit of 50 to 60 men entered Athens, driving out the Eighteenth Ohio Volunteers. As federal soldiers retreated, civilians attached themselves to the Confederate unit and attacked the fleeing northerners. Incensed at being driven from the town, Mitchel ordered Turchin to retake Athens. Accordingly, Turchin sent his Eighth Brigade back into Athens to reestablish control. For Turchin and his men, simply regaining control of the town was not enough. According to contemporary sources, Turchin allowed his men two or three hours to target civilian property. In many instances, federal soldiers went beyond the pale of acceptable conduct and plundered houses, destroyed personal property, and tore down fence railings.

At first, the “Sack of Athens” did not receive much attention from U.S. Army officers or northern newspapers. It was not until early July, when Buell arrived in Huntsville, that Turchin faced disciplinary action. Buell charged Turchin with several offenses, chiefly neglect of duty, conduct unbecoming an officer, and disobedience of orders. Throughout the court-martial, Turchin insisted he was innocent of all charges except an order that banned wives from camp, as Nadine Turchin frequently joined him in the field. Turchin observed at the end of his trial that the U.S. Army would never put down the rebellion until it conducted the war in the European manner. He advised that federal troops should live off the land and destroy the South’s resources.

Although members of the court-martial found Turchin guilty on all charges, they urged Buell to grant the defendant clemency because of the “exciting circumstances” of the action. Buell refused to be lenient and ordered Turchin dismissed from the service. But for the previous several weeks, Turchin’s wife and influential Illinois statesmen had been seeking redress in Washington, D.C. Their efforts were successful: Secretary of War Edwin Stanton recommended to Congress that Turchin be promoted to brigadier general. The promotion became official in mid-July and invalidated the court-martial verdict because officers could only be tried by equals or superior officers. As a result of the promotion, Turchin outranked six of the court’s seven members. Unfortunately for Buell and southerners, the methods Turchin used to hold secessionists accountable for their actions were gaining widespread acceptance in the army and in the North. By the summer of 1862, conciliation was no longer a viable military strategy.

After his trial and promotion, Turchin spent time in Chicago before returning to active service in the fall of 1862. For health reasons, he resigned his commission in October 1864. In 1865, Turchin authored Military Rambles, and in 1888 penned The Campaign and Battle of Chickamauga. Turchin died in an insane asylum in January 1901.

Turchin’s legacy to the state of Alabama—and to the nation as a whole—is significant. Although Turchin was not alone in attempting to target civilians who actively supported the Confederacy, his theories on war helped to develop a mentality among U.S. military officers and officials in Washington that targeting certain civilians was a necessary wartime measure. Turchin’s punitive approach is most clearly evident in General William Tecumseh Sherman’s “March to the Sea.”

Additional Resources

Bradley, George C., and Richard L. Dahlen. From Conciliation to Conquest: The Sack of Athens and the Court-Martial of Colonel John B. Turchin. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006.

Chicoine, Stephen. John Basil Turchin and the Fight to Free the Slaves. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 2003.

Danielson, Joseph. “‘Twill Be Done Again’: Union Occupation of North Alabama, April Through August, 1862.” Master’s thesis, University of Alabama, 2004.

Grimsley, Mark. The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy Toward Southern Civilians, 1861-1865. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995.