Lost Cause Ideology

The Lost Cause Title Page

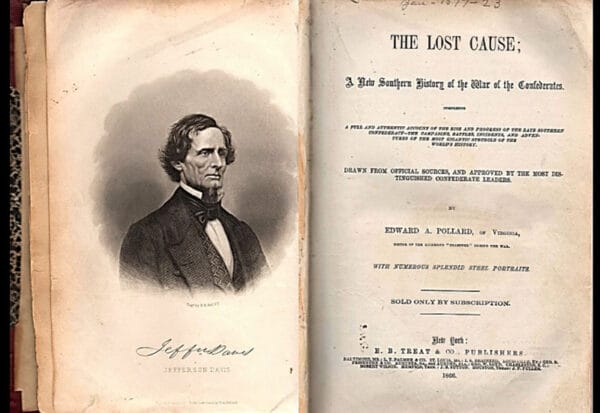

The term “Lost Cause” emerged at the end of the Civil War when Edward Pollard, editor of the Richmond Examiner, popularized it with his book The Lost Cause, which chronicled the Confederacy’s demise. The term swiftly came into common use as a reference not only to military defeat, but defeat of the “southern way of life”—a phrase that generally referred to the South of the antebellum period, when plantation slavery was still intact. Since the late nineteenth century, historians have used the term “Lost Cause” to describe a particular belief system as well as commemorative activities that occurred in the South for decades after the Civil War. Commonly held beliefs were that the war was fought over states’ rights and not slavery, that slavery was a benevolent institution that offered Christianity to African “savages,” and that the war was a just cause in the eyes of God. Commemorative activities included erecting Confederate monuments and celebrating Confederate Memorial Day.

The Lost Cause Title Page

The term “Lost Cause” emerged at the end of the Civil War when Edward Pollard, editor of the Richmond Examiner, popularized it with his book The Lost Cause, which chronicled the Confederacy’s demise. The term swiftly came into common use as a reference not only to military defeat, but defeat of the “southern way of life”—a phrase that generally referred to the South of the antebellum period, when plantation slavery was still intact. Since the late nineteenth century, historians have used the term “Lost Cause” to describe a particular belief system as well as commemorative activities that occurred in the South for decades after the Civil War. Commonly held beliefs were that the war was fought over states’ rights and not slavery, that slavery was a benevolent institution that offered Christianity to African “savages,” and that the war was a just cause in the eyes of God. Commemorative activities included erecting Confederate monuments and celebrating Confederate Memorial Day.

When describing the Lost Cause, historians have employed the terms “myth,” “cult,” “civil religion,” “Confederate tradition,” and “celebration” to explain this southern phenomenon. Many of these terms are used interchangeably, but they all refer to a conservative movement in the postwar South that was steeped in the agrarian traditions of the Old South and that complicated efforts to create a “New South.” For diehard believers in the Lost Cause, the term New South was repugnant and implied that there was something wrong with the values and traditions of the antebellum past. For individuals devoted to the idea of the Lost Cause, the Old South still served as a model for race relations (blacks should be deferential to whites as under slavery), gender roles (women should be deferential to their fathers, brothers, and husbands), and class interactions (poor whites should defer to wealthier whites). Moreover, individuals believed that the Confederacy, which sought to preserve the southern way of life, should be respected and its heroes, as well as its heroines, should be revered. Indeed, white southerners, for whom the Lost Cause was sacred, argued that the members of the Confederate generation fought for a just cause—states’ rights—and were to be honored for their sacrifices in defense of constitutional principle.

Ladies Memorial Association in Talladega

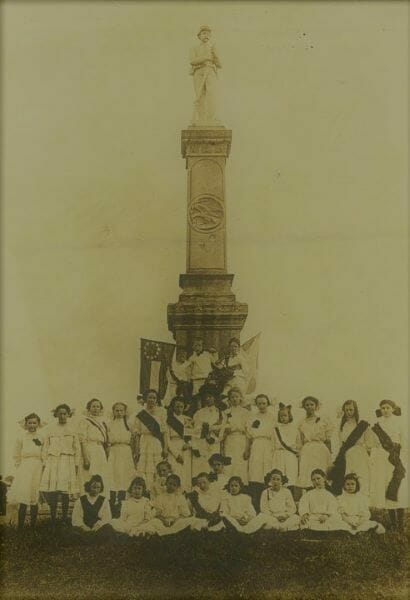

Historians describe the Lost Cause as a movement with three phases: bereavement, celebration, and finally, vindication. The first phase, bereavement, occurred in the wake of defeat and lasted through the period of Reconstruction in 1877 and was marked by the establishment of ladies’ memorial associations throughout the South, the creation of Confederate cemeteries, and the unveiling of the first Confederate monuments. Ladies’ memorial associations also lobbied for the creation of Confederate Memorial Day, which was held on April 26, the day Gen. Joseph E. Johnston surrendered in North Carolina, or May 10, the day Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson died. On those days, white southerners went to their community cemetery for commemorative ceremonies and laid flowers on the graves of veterans. Confederate Memorial Day is still commemorated in southern states, but it is not always officially sanctioned by state governments.

Ladies Memorial Association in Talladega

Historians describe the Lost Cause as a movement with three phases: bereavement, celebration, and finally, vindication. The first phase, bereavement, occurred in the wake of defeat and lasted through the period of Reconstruction in 1877 and was marked by the establishment of ladies’ memorial associations throughout the South, the creation of Confederate cemeteries, and the unveiling of the first Confederate monuments. Ladies’ memorial associations also lobbied for the creation of Confederate Memorial Day, which was held on April 26, the day Gen. Joseph E. Johnston surrendered in North Carolina, or May 10, the day Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson died. On those days, white southerners went to their community cemetery for commemorative ceremonies and laid flowers on the graves of veterans. Confederate Memorial Day is still commemorated in southern states, but it is not always officially sanctioned by state governments.

When the Reconstruction period ended in 1877, southern conservatives resumed control of their state governments, and it is during this phase that regional enthusiasm for the Lost Cause increased. What had been an era of mourning turned into years of celebrating the Confederacy and its heroes, especially Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Jefferson Davis. Lost Cause supporters also lauded the principles of states’ rights and white supremacy, as well as women of the Confederacy, whose contributions to the southern cause were legendary. This phase, lasting from the 1870s through the 1890s, saw the development and publication of Lost Cause literature that expressed white southerners’ loyalty to the principle of states’ rights and belief in white supremacy. The literature also offered a revisionist view of the conflict, describing slavery as a benevolent institution, the enslaved as faithful servants, and the period of Reconstruction as a “tragic era.” To those who subscribed to the Lost Cause, the Confederacy suffered military defeat, but not the defeat of its values and belief system. Major figures in Alabama history who defended these beliefs included J. J. D. Renfroe, John Tyler Morgan, Clement C. Clay and his wife Virginia, Augusta Jane Evans Wilson, and George Washington Stone.

The Confederate celebration expanded in the 1890s, as the South became a fertile breeding ground for the foundation of new Confederate organizations for both men and women, including the United Confederate Veterans, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and the Sons of Confederate Veterans. White political supremacy was sanctioned by every southern state, including Alabama in its 1901 Constitution, and states’ rights appeared secure. Moreover, some northern whites, threatened by ever-increasing ethnic diversity in their region, expressed both sympathy and admiration for southern whites, giving the belief system extended life in southern culture.

Confederate Monument

Also during the 1890s, the Lost Cause philosophy experienced significant change as the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) came to dominate the leadership of the movement and made vindication of the Confederacy its guiding principle. In addition to honoring the Confederacy and its heroes, these women placed critical importance on preserving and transmitting what they perceived were the traditional cultural values of the South for future generations. Reclaiming Civil War history and infusing it with a pro-southern interpretation became a primary objective of the Lost Cause after 1890. In addition to supporting the publication of pro-southern literature, the Daughters (as UDC members were also known), continued the work of building monuments and supplemented that work with building homes for indigent and aging Confederate veterans and women, monitoring public schools to insure that children were taught the Lost Cause version of the southern past, and sponsoring scholarships for the study and preservation of Confederate history in both northern and southern colleges and universities. The Daughters’ goal in all of their work was the vindication of the men and women of the 1860s, particularly their mothers and fathers. Well known UDC members in Alabama included Virginia Clay Clopton, who was once the state president of the Alabama division and also a well-known supporter of woman suffrage, though only for white women.

Confederate Monument

Also during the 1890s, the Lost Cause philosophy experienced significant change as the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) came to dominate the leadership of the movement and made vindication of the Confederacy its guiding principle. In addition to honoring the Confederacy and its heroes, these women placed critical importance on preserving and transmitting what they perceived were the traditional cultural values of the South for future generations. Reclaiming Civil War history and infusing it with a pro-southern interpretation became a primary objective of the Lost Cause after 1890. In addition to supporting the publication of pro-southern literature, the Daughters (as UDC members were also known), continued the work of building monuments and supplemented that work with building homes for indigent and aging Confederate veterans and women, monitoring public schools to insure that children were taught the Lost Cause version of the southern past, and sponsoring scholarships for the study and preservation of Confederate history in both northern and southern colleges and universities. The Daughters’ goal in all of their work was the vindication of the men and women of the 1860s, particularly their mothers and fathers. Well known UDC members in Alabama included Virginia Clay Clopton, who was once the state president of the Alabama division and also a well-known supporter of woman suffrage, though only for white women.

Confederate Memorial Park

The heyday of the Lost Cause occurred between 1877 and World War I, but its legacy remained a powerful influence in the South well into the twentieth century. Generations of children were raised on the Lost Cause ideology, and many of them went on to actively resist desegregation at mid-century. Although not all white southerners accepted the ideology of the Lost Cause, those who did included Alabama’s Eugene “Bull” Connor and George Wallace. In fact, the successes of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s became the “lost cause” of white supremacists that, like their forbears, draped themselves in the mantle of the Confederate battle flag. Moreover, the racial beliefs found in the Lost Cause were very similar to those held by segregationists.

Confederate Memorial Park

The heyday of the Lost Cause occurred between 1877 and World War I, but its legacy remained a powerful influence in the South well into the twentieth century. Generations of children were raised on the Lost Cause ideology, and many of them went on to actively resist desegregation at mid-century. Although not all white southerners accepted the ideology of the Lost Cause, those who did included Alabama’s Eugene “Bull” Connor and George Wallace. In fact, the successes of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s became the “lost cause” of white supremacists that, like their forbears, draped themselves in the mantle of the Confederate battle flag. Moreover, the racial beliefs found in the Lost Cause were very similar to those held by segregationists.

Today, the Lost Cause is largely a topic of study for historical research, although its defenders still exist as members of Confederate heritage groups as well as members of more radical organizations such as the League of the South (which continues to believe in the possibility of the South seceding again), who are generally referred to as “neo-Confederates.” Moreover, in Alabama and elsewhere in the South, tangible evidence of the Lost Cause remains, most often in the form of the battle flag or the single marble Confederate soldier standing sentinel on courthouse grounds. Yet as the South changes, so does its reaction to those symbols, which are slowly becoming relics of another place and time.

Additional Resources

Cox, Karen L. Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003.

———. Dreaming of Dixie: How the South Was Created in American Popular Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Foster, Gaines M. Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Gallagher, Gary M., and Alan T. Nolan, eds. The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000.

Wilson, Charles Reagan. Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865-1920. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1983.