Presidential Reconstruction in Alabama

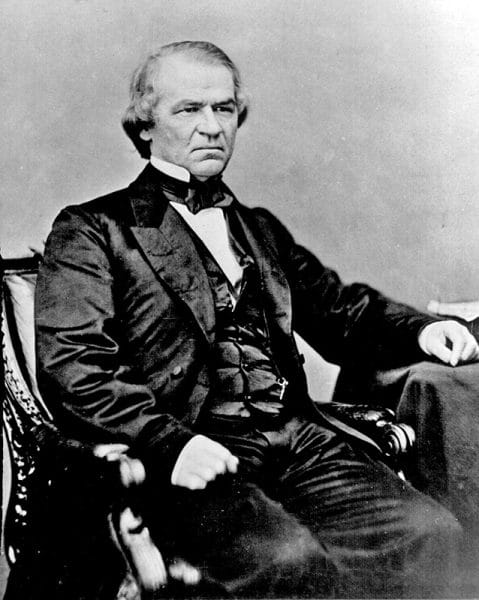

Andrew Johnson

Presidential Reconstruction is the general term for the political and societal changes that began taking place at the end of the Civil War and emancipation, beginning in the summer of 1865. It is called Presidential Reconstruction because the procedures were dictated by Pres. Andrew Johnson. The most notable characteristic of this era was the strong influence of planters and ex-Confederates over the direction of southern government. This phase of the Reconstruction process came to a close in March 1867, when Republicans in Congress, who viewed Johnson’s actions to protect the rights of freedpeople as insufficient, took control of the Reconstruction process and decreed that the process should begin anew with a focus on black suffrage.

Andrew Johnson

Presidential Reconstruction is the general term for the political and societal changes that began taking place at the end of the Civil War and emancipation, beginning in the summer of 1865. It is called Presidential Reconstruction because the procedures were dictated by Pres. Andrew Johnson. The most notable characteristic of this era was the strong influence of planters and ex-Confederates over the direction of southern government. This phase of the Reconstruction process came to a close in March 1867, when Republicans in Congress, who viewed Johnson’s actions to protect the rights of freedpeople as insufficient, took control of the Reconstruction process and decreed that the process should begin anew with a focus on black suffrage.

Origins of Reconstruction

The events that led up to Reconstruction can be traced back far before the Civil War to the institution of slavery and increasing concern among southern planters and other powerful interests about protecting the institution from outside interference. In Alabama, these issues were complicated by longstanding rivalries between the Whig-dominated plantation belt, where political forces favored government support for economic development and moderation regarding sectionalism, and the predominantly Democratic northern half of the state, where limited government, low taxes, and the interests of small farmers (the hallmarks of Jacksonian democracy) were paramount. These Democrats traditionally controlled the state, and as the issue of slavery’s expansion heated up after the Mexican War, the Democrats, with their strong advocacy of states’ rights, gained even more power. But the election of Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans at the national level in 1860 scrambled existing political patterns. The southern and central part of the state voted for immediate secession from the Union, mostly by large margins, but the north Alabama hill country and the Tennessee Valley voted for a more moderate but ill-defined alternative.

After Alabama’s secession in January 1861, most whites rallied to the Confederate cause, but many Alabamians maintained support for neutrality; in the poorer, non-slaveholding enclaves in the northern hills, pro-Union sentiments remained strong. This pattern was reinforced geographically in early 1862, when Union troops overran the Tennessee Valley. They would control this area for most of the war, and the federal presence made it possible for dissidents and draft resisters to confront Confederate authority. Some 3,000 whites joined the First Alabama Cavalry and other federal units. The result was a bitter Alabama civil war within the Civil War, which often developed along class and neighborhood lines. Peace sentiment and Unionism spread where support for secession had been weak.

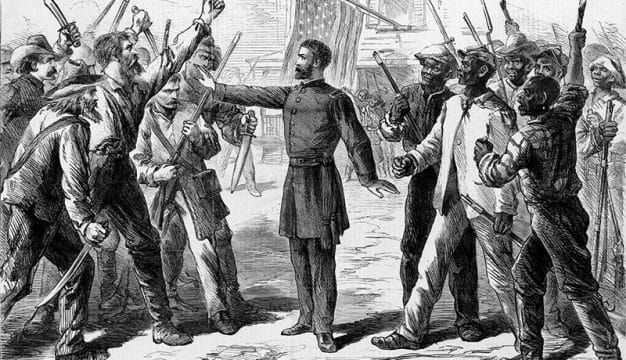

The war’s destruction reached the central Alabama cotton belt only in its final weeks. The surrender of the Confederate armies in Alabama in May 1865 started a chaotic transition period for the enslaved population, which had mostly waited out the events that were transpiring up until that date. Freedpeople headed for the nearest town or Union Army camp, or sought freedom on other plantations. Vast numbers sought reunion with dispersed family members. For those who remained on plantations, the main focus was ending slavery’s close supervision, whippings, and harsh working conditions. Their increasingly vocal demands for immediate change, as well as slaveowners’ fears of potential anarchy, underlay the political conflict that would define Reconstruction.

Emancipation and Its Aftermath

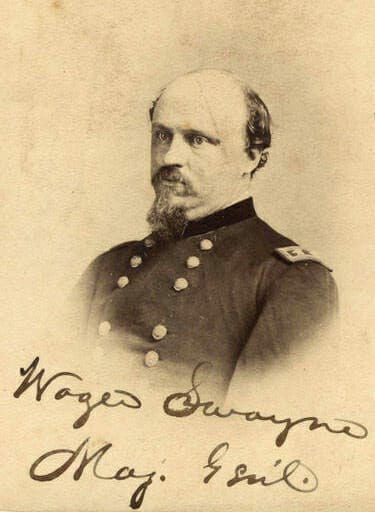

Wager Swayne

In the months after the Confederate surrender, the Union Army oversaw the liberation process. Troops enforced emancipation in the countryside and punished instances of whipping among newly freed plantation workers, but they also forcibly discouraged migration to the region’s few cities among the many freedpeople who wished to do so. Fearful of retaliatory violence, former slave owners at first welcomed the military presence and the efforts of the federal Freedmen’s Bureau to restore the plantation agriculture system. As the months went by, however, the bureau and its commander, Gen. Wager T. Swayne, became more sharply resented by former Confederates.

Wager Swayne

In the months after the Confederate surrender, the Union Army oversaw the liberation process. Troops enforced emancipation in the countryside and punished instances of whipping among newly freed plantation workers, but they also forcibly discouraged migration to the region’s few cities among the many freedpeople who wished to do so. Fearful of retaliatory violence, former slave owners at first welcomed the military presence and the efforts of the federal Freedmen’s Bureau to restore the plantation agriculture system. As the months went by, however, the bureau and its commander, Gen. Wager T. Swayne, became more sharply resented by former Confederates.

As this transition unfolded, the initial stages of Presidential Reconstruction began. Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, had been a militant Unionist leader from Tennessee, and thus it was believed that he would punish the former Confederate leadership. In his initial act regarding Alabama, he chose Lewis Parsons, a prewar Whig and reported wartime peace supporter, as the provisional governor in June, leading former secessionists to fear reprisals. Soon after, Johnson’s policy turned in the direction of conciliating ex-Confederates and pardoning slaveowners with large holdings, who had been subject to prosecution under wartime confiscation laws. Johnson rejected calls for extending voting rights to freed blacks and urged the return of authority to the state governments with few changes to their constitutions. Following Johnson’s lead, Parsons restored most ex-Confederate local officials to power. Under Presidential Reconstruction, outright Unionists faced serious discrimination and were embroiled in conflict with returning Confederates.

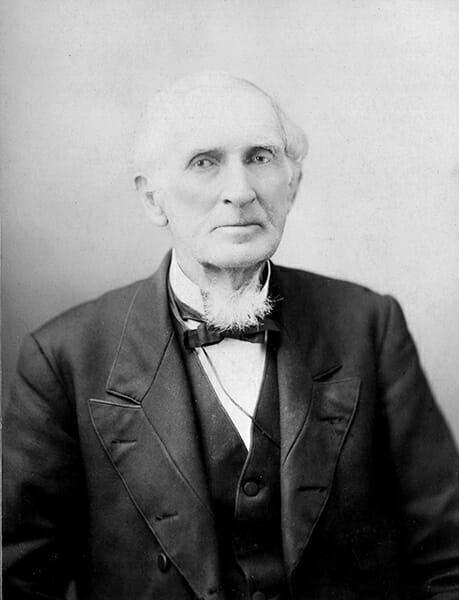

Robert M. Patton

Alabama held a constitutional convention in September 1865, in which the delegates agreed to disavow secession and the debts incurred by the state prior to and during the war, outlaw slavery, and reallocate representation in the legislature based solely on the white population, which increased north Alabama’s power. Other important issues included reconstituting the state’s labor system and minimizing interruptions in agricultural production. Few supporters of secession participated in approving the new constitution, and the newly elected governor, Robert M. Patton, was a former Whig opponent of secession. Patton was a moderate who favored outside investment, especially railroad development. When the new legislature passed a number of vagrancy and other laws targeted at freedpeople, known as “Black Codes,” Patton vetoed several of the harsher provisions to avoid northern criticism. His opposition to extreme racism likely averted the violent race riots that plagued places such as New Orleans and Memphis and helped to undermine Presidential Reconstruction.

Robert M. Patton

Alabama held a constitutional convention in September 1865, in which the delegates agreed to disavow secession and the debts incurred by the state prior to and during the war, outlaw slavery, and reallocate representation in the legislature based solely on the white population, which increased north Alabama’s power. Other important issues included reconstituting the state’s labor system and minimizing interruptions in agricultural production. Few supporters of secession participated in approving the new constitution, and the newly elected governor, Robert M. Patton, was a former Whig opponent of secession. Patton was a moderate who favored outside investment, especially railroad development. When the new legislature passed a number of vagrancy and other laws targeted at freedpeople, known as “Black Codes,” Patton vetoed several of the harsher provisions to avoid northern criticism. His opposition to extreme racism likely averted the violent race riots that plagued places such as New Orleans and Memphis and helped to undermine Presidential Reconstruction.

Many Republicans in Congress were angered by Johnson’s wholesale pardons of former Confederates, opposition to black suffrage, and failure to act against the repressive new Black Codes. After Congress met in late 1865, the Republican majority refused to seat the representatives from the former Confederacy without further assurances of loyalty and protections for freedpeople and Unionists. In response, he vetoed civil rights protections proposed by Congress in February 1866 that would have assured the laws were not race-based and also an extension of the Freedmen’s Bureau, charged with protecting the former slaves. A constitutional deadlock ensued, with the president recognizing the southern states as being in the Union and Congress denying that they were and barring their representatives. The South remained in constitutional limbo until Johnson’s allies in Congress were soundly defeated in the midterm election of November 1866. Buoyed by northern support, the Republican majority favored a 14th Amendment to the Constitution, guaranteeing equal rights before the law short of suffrage, and a ban on officeholding by former government officials who had supported the Confederacy. Patton was the only southern governor to favor ratification, hoping to head off the threat of more extreme Reconstruction efforts and black suffrage, but the Alabama legislature rejected his counsel. These events set the stage for the Republican Congress to take control of oversight in March 1867, a shift that was known variously as Military Reconstruction, Radical Reconstruction, and, more broadly, Congressional Reconstruction. The central provision of Congressional Reconstruction was a decree to start the process over again on the basis of equal suffrage.

Further Reading

- Fitzgerald, Michael W. Splendid Failure: Postwar Reconstruction in the American South. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2007.

- ———. Reconstruction in Alabama: From Civil War to Redemption in the Cotton South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2017.

- Fleming, Walter D. Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama. New York: Columbia University Press, 1905.

- McMillan, Malcolm Cook. Constitutional Development in Alabama, 1791-1901: A Study in Politics, the Negro, and Sectionalism. Spartanburg, S.C.: The Reprint Company, 1978.

- Raines, Howell. Silent Cavalry: How Union Soldiers from Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta—And Then Got Written Out of History. New York: Crown, 2023.