Freedom Quilting Bee

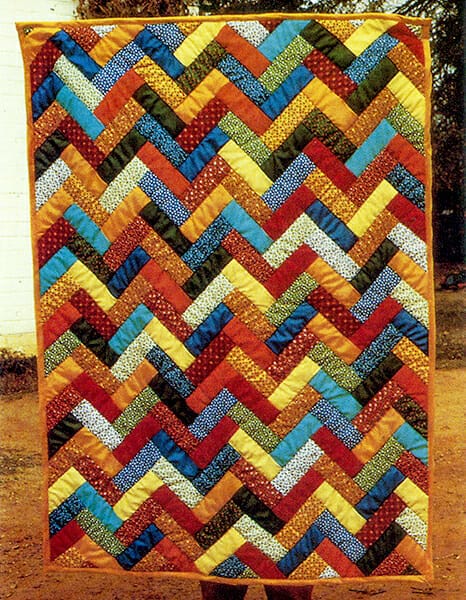

Coat of Many Colors

The Freedom Quilting Bee is a quilting cooperative established in 1966 by a group of African American women in the community of Rehoboth, 46 miles from Selma, in Wilcox County. The groups arose during the civil rights movement and is heralded for having spawned a renaissance in the popularity of quilting in American interior décor in the 1960s. The Freedom Quilting Bee has in recent years been confused with the nationally known Gee’s Bend Quilters Collective, a group of quilters who reside in the nearby community of Boykin (formerly Gee’s Bend). Some quilters in the Freedom Quilting Bee have belonged to both groups.

Coat of Many Colors

The Freedom Quilting Bee is a quilting cooperative established in 1966 by a group of African American women in the community of Rehoboth, 46 miles from Selma, in Wilcox County. The groups arose during the civil rights movement and is heralded for having spawned a renaissance in the popularity of quilting in American interior décor in the 1960s. The Freedom Quilting Bee has in recent years been confused with the nationally known Gee’s Bend Quilters Collective, a group of quilters who reside in the nearby community of Boykin (formerly Gee’s Bend). Some quilters in the Freedom Quilting Bee have belonged to both groups.

The Freedom Quilting Bee was born in the civil rights movement as a way for poor black craftswomen in the Alabama Black Belt to earn money for their families. Most of the members rallied for voting rights in the Selma-to-Montgomery March, or in Camden, the Wilcox County seat. Despite the passage of civil rights legislation in 1964 and 1965, a direct outcome of the Selma march, the region remained in turmoil.

Walter, Frances

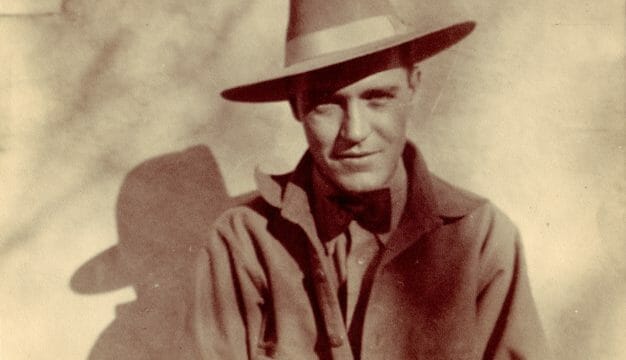

An Episcopal priest, Father Francis X. Walter, a Mobile native, had come home to Alabama from a church in New Jersey to head the Selma Inter-religious Project (SIP), a coalition of 10 nationwide religious denominations serving as a spiritual presence in Selma in the aftermath of the march. While lost driving around near the remote community of Possum Bend in Wilcox County, he spied a clothesline with three quilts in bold, primary colors, unlike any he had seen before. As he approached the home to inquire about the quilts, a black woman who saw him coming fled to the back woods. Such were race relations in the Black Belt, even after passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Soon after that backwoods encounter with Ora McDaniels, he stopped by the home of another local African American quilter to discuss the works. At the time, the Op Art movement, which focused on bold geometric shapes and patterns, was popular in the art world of New York City. Walter saw similar themes expressed in the patterns on the quilts and believed that the quilters around Selma could benefit from forming a quilting coalition to fund civil rights activities. After a friend in New York suggested a quilt auction as a fund raiser, Walter met with Ella Saulsbury, a local field representative from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and then returned with her to visit McDaniels to discuss placing some of the Wilcox county quilts in the auction.

Walter, Frances

An Episcopal priest, Father Francis X. Walter, a Mobile native, had come home to Alabama from a church in New Jersey to head the Selma Inter-religious Project (SIP), a coalition of 10 nationwide religious denominations serving as a spiritual presence in Selma in the aftermath of the march. While lost driving around near the remote community of Possum Bend in Wilcox County, he spied a clothesline with three quilts in bold, primary colors, unlike any he had seen before. As he approached the home to inquire about the quilts, a black woman who saw him coming fled to the back woods. Such were race relations in the Black Belt, even after passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Soon after that backwoods encounter with Ora McDaniels, he stopped by the home of another local African American quilter to discuss the works. At the time, the Op Art movement, which focused on bold geometric shapes and patterns, was popular in the art world of New York City. Walter saw similar themes expressed in the patterns on the quilts and believed that the quilters around Selma could benefit from forming a quilting coalition to fund civil rights activities. After a friend in New York suggested a quilt auction as a fund raiser, Walter met with Ella Saulsbury, a local field representative from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and then returned with her to visit McDaniels to discuss placing some of the Wilcox county quilts in the auction.

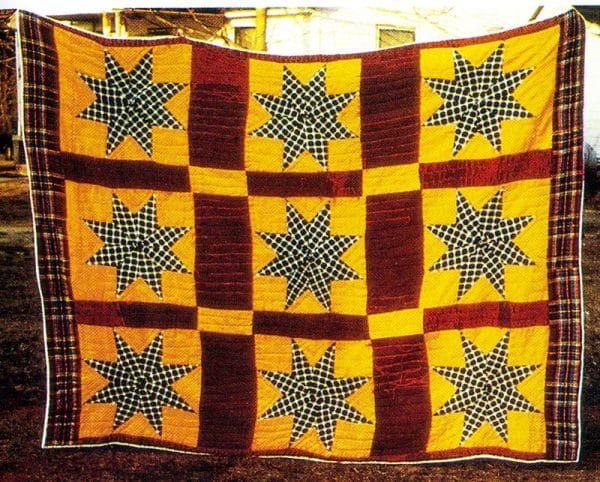

Star Pattern Quilt

An informal group soon coalesced to collect quilts for sale at the New York auction. As Walter went door-to-door for the project, however, sentiment emerged among the quilters for a more organized, permanent quilting cooperative for black craftswomen in the area. Quilter Minder Coleman of Alberta, former president of Gee’s Bend Farms, Inc., a New Deal cooperative agricultural community, envisioned a quilting business and offered to serve as chair. Momentum gathered for the establishment of a cooperative, with members earning the proceeds from sales of the quilts. Thus, on March 26, 1966, the Freedom Bee was officially organized, and those present elected officers, set up a board of directors, and adopted a charter. The group counted 60 members from across the Black Belt, with its nucleus in Rehoboth (also known then as Route 1, Alberta), because that was the home of manager Estelle Witherspoon, a skilled and politically savvy community leader.

Star Pattern Quilt

An informal group soon coalesced to collect quilts for sale at the New York auction. As Walter went door-to-door for the project, however, sentiment emerged among the quilters for a more organized, permanent quilting cooperative for black craftswomen in the area. Quilter Minder Coleman of Alberta, former president of Gee’s Bend Farms, Inc., a New Deal cooperative agricultural community, envisioned a quilting business and offered to serve as chair. Momentum gathered for the establishment of a cooperative, with members earning the proceeds from sales of the quilts. Thus, on March 26, 1966, the Freedom Bee was officially organized, and those present elected officers, set up a board of directors, and adopted a charter. The group counted 60 members from across the Black Belt, with its nucleus in Rehoboth (also known then as Route 1, Alberta), because that was the home of manager Estelle Witherspoon, a skilled and politically savvy community leader.

Freedom Quilting Bee

In New York, Walter arranged for friends to stage two quilt auctions that were promoted as ways to help black women fighting for civil rights in the South. Produced by former Alabamians, the first auction, held on March 27, 1966, took place in a photography studio near Central Park West. Advertising consisted of a promotional flyer, a sign in the studio window, and word of mouth. One of the promoters also arranged for New York City wholesale home furnishings fabric houses to donate and ship cloth scraps to Rehobeth for use in the quilts. The second auction was held on May 24, 1966, in the basement hall of the Unitarian-Universalist Community Church of New York. By that time, the promoters found a communications professional to do volunteer publicity, placing a paragraph in The New York Times, courtesy of a Mississippi-born reporter, as well as printing posters and spreading the word.

Freedom Quilting Bee

In New York, Walter arranged for friends to stage two quilt auctions that were promoted as ways to help black women fighting for civil rights in the South. Produced by former Alabamians, the first auction, held on March 27, 1966, took place in a photography studio near Central Park West. Advertising consisted of a promotional flyer, a sign in the studio window, and word of mouth. One of the promoters also arranged for New York City wholesale home furnishings fabric houses to donate and ship cloth scraps to Rehobeth for use in the quilts. The second auction was held on May 24, 1966, in the basement hall of the Unitarian-Universalist Community Church of New York. By that time, the promoters found a communications professional to do volunteer publicity, placing a paragraph in The New York Times, courtesy of a Mississippi-born reporter, as well as printing posters and spreading the word.

Star Design Quilt

Prior to that first auction, Walter had travelled up and down the roads in the area, asking for quilts to be shipped off. Some women took stitchwork directly from their beds. Patterns reflected styles spanning at least a century of black quilting in the area, including the Roman Cross, Pine Burr, and Chestnut Bud. Especially poignant to prospective buyers were worn-out denim swatches made from blue jeans after their owners could no longer wear them in the corn and cotton fields. The auctions stirred momentum, and quilts went from $10-15 to $100 and upwards after the first two events. Famed New York decorator Sister Parrish purchased quilted works from the co-op for use in decorating her clients’ homes, and Vogue editor Diana Vreeland promoted the quilting styles in the influential fashion magazine. High-end department stores such as Bloomingdale’s and Saks Fifth Avenue bought quilts to sell to their customers, and The New York Times covered the group and generated publicity for the women and their work.

Star Design Quilt

Prior to that first auction, Walter had travelled up and down the roads in the area, asking for quilts to be shipped off. Some women took stitchwork directly from their beds. Patterns reflected styles spanning at least a century of black quilting in the area, including the Roman Cross, Pine Burr, and Chestnut Bud. Especially poignant to prospective buyers were worn-out denim swatches made from blue jeans after their owners could no longer wear them in the corn and cotton fields. The auctions stirred momentum, and quilts went from $10-15 to $100 and upwards after the first two events. Famed New York decorator Sister Parrish purchased quilted works from the co-op for use in decorating her clients’ homes, and Vogue editor Diana Vreeland promoted the quilting styles in the influential fashion magazine. High-end department stores such as Bloomingdale’s and Saks Fifth Avenue bought quilts to sell to their customers, and The New York Times covered the group and generated publicity for the women and their work.

Estelle Witherspoon and Mama Willie Abrams

The quilts caught the attention of influential artists, including painter Lee Krasner, widow of abstract expressionist painter Jackson Pollock, and the quilters exhibited at the Smithsonian Institution. Promoters from New York ran sewing schools at the co-op building that rose up in a former cornfield in Alberta. The women learned to conduct business, and for the first time, they earned money, enabling them to acquire indoor bathrooms and roofs that did not leak and to provide their children with high school graduation rings and college tuition. They also spurred a nationwide quilting revival.

Estelle Witherspoon and Mama Willie Abrams

The quilts caught the attention of influential artists, including painter Lee Krasner, widow of abstract expressionist painter Jackson Pollock, and the quilters exhibited at the Smithsonian Institution. Promoters from New York ran sewing schools at the co-op building that rose up in a former cornfield in Alberta. The women learned to conduct business, and for the first time, they earned money, enabling them to acquire indoor bathrooms and roofs that did not leak and to provide their children with high school graduation rings and college tuition. They also spurred a nationwide quilting revival.

In the 1970s, the co-op decided to limit the number of patterns it produced to meet market requirements. The quilters no longer crafted original, one-of-a-kind showpieces, and the change drew some criticism. But members were committed to improving their lives and the lives of their children and raising the economic standards in their community. In addition to quilting, the group filled sewing contracts for Sears, sold works through larger co-ops, and took on projects through the New York-based Rural Development Leadership Network. By the mid-1990s, many of the members had retired, died, or taken steadier jobs outside the county, and the Freedom Quilting Bee lost the momentum.

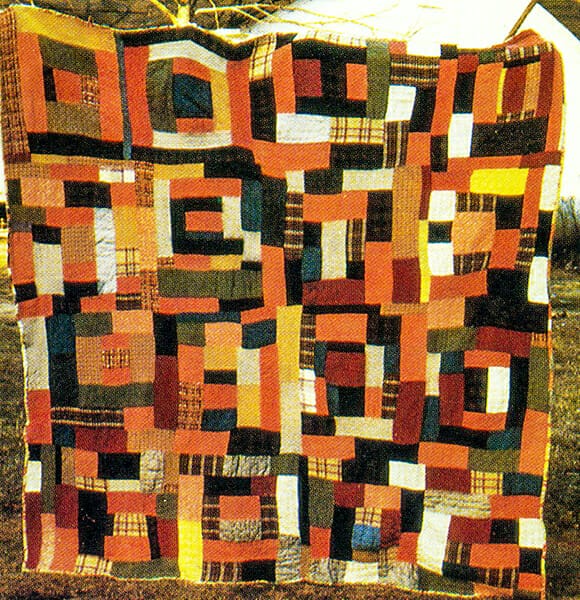

Crazy Quilt

Despite these changes, a small group continued the work. Local students received summer training. Then in 2004, Hurricane Ivan damaged the Bee’s traditional workplace, the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Sewing Center, causing the handful of remaining quilters to work in the living room of manager Rennie Miller. Retired from management in New York state, Miller had received a college education paid for in part by monies earned by her mother, Nettie Young, an early member of the Freedom Quilting Bee. Another member, Lucy Marie Mingo, was the most educated member, having studied on scholarship at Spring Hill College in Mobile. One of her quilts is now in the possession of the Birmingham Museum of Art.

Crazy Quilt

Despite these changes, a small group continued the work. Local students received summer training. Then in 2004, Hurricane Ivan damaged the Bee’s traditional workplace, the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Sewing Center, causing the handful of remaining quilters to work in the living room of manager Rennie Miller. Retired from management in New York state, Miller had received a college education paid for in part by monies earned by her mother, Nettie Young, an early member of the Freedom Quilting Bee. Another member, Lucy Marie Mingo, was the most educated member, having studied on scholarship at Spring Hill College in Mobile. One of her quilts is now in the possession of the Birmingham Museum of Art.

Renovations to the portions of the building with storm damage have never been completed because of lack of community interest, among other obstacles. In May 2011, Nettie Young, the last living member of the original Freedom Quilting Bee and original board, died. Since that time, interest and participation in the group dwindled, and in 2012, Rennie Miller officially closed the Bee. She hopes to revive the historic co-op with help from outside sources.

Further Reading

- Callahan, Nancy. The Freedom Quilting Bee. 1987. Reprint, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005.