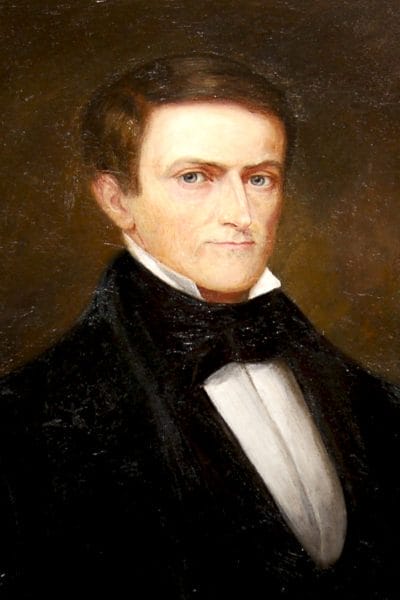

John A. Winston (1853-57)

John A. Winston (1812-1871) was Alabama’s first native-born governor. After his election to the Alabama House of Representatives in 1840 and again in 1842, he served in the State Senate from 1843 to 1853. In the decade before the outbreak of the Civil War, he emerged as the leader of the states’ rights wing of the Alabama Democratic Party. As governor between 1853 and 1857, he established a forceful record on behalf of the strict states’ rights doctrines of Jacksonian democracy.

John A. Winston

John Anthony Winston was born on September 4, 1812, in the Tennessee Valley region of Madison County. Educated in private schools, he attended Cumberland College in Nashville, Tennessee, and married Mary Agnes Walker in 1832. In 1835, the couple settled in Sumter County in the western Black Belt, where Winston had purchased a large plantation. By 1844, he was operating a successful cotton commission firm in Mobile and soon amassed enough wealth to acquire additional plantations in Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Texas.

John A. Winston

John Anthony Winston was born on September 4, 1812, in the Tennessee Valley region of Madison County. Educated in private schools, he attended Cumberland College in Nashville, Tennessee, and married Mary Agnes Walker in 1832. In 1835, the couple settled in Sumter County in the western Black Belt, where Winston had purchased a large plantation. By 1844, he was operating a successful cotton commission firm in Mobile and soon amassed enough wealth to acquire additional plantations in Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Texas.

Despite his economic success, Winston’s private life was stormy. Following the death of his first wife in 1842, he married Mary W. Longwood, but this marriage ended in a divorce granted by the legislature in 1850. The marriage effectively ended in 1847 when Winston discovered that his wife was having an affair with Sidney S. Perry, the family physician. Winston promptly shot the doctor to death. He suffered no penalty when county magistrates ruled that his action was “justifiable homicide.”

Despite Winston’s turbulent private life, his initial public image was one of political moderation. He was instrumental in preventing the Alabama delegation at the 1848 Baltimore convention of the Democratic Party from walking out, at the urging of strident states’ rights supporter William Lowndes Yancey, when the convention refused to accept Yancey’s Alabama Platform, which demanded congressional protection of slavery in the federal territories. Two years later, during the sectional crisis provoked by debates leading to the Compromise of 1850, Winston again rejected the extreme pro-secession, southern rights stand of Yancey and his supporters. Soon after north Alabama Democrats joined south Alabama Whigs in a coalition Unionist Party to stave off threats of secession, Winston took the lead in reorganizing the Democrats along traditional partisan lines. As a reward for his party loyalty, he secured the Democratic gubernatorial nomination in 1853. He gained the governorship with no opposition when his Whig opponent dropped out of the race.

In his inaugural address in December 1853, Winston outlined his states’ rights philosophy. Like a good Jacksonian Democrat, he deplored the use of state funds—what he would call the people’s money—to assist private corporations in banking and transportation. Whatever economic benefits might result from state-supported development were more than offset, in Winston’s mind, by the corrupting influence of corporate power and the dangers that it posed to the individual liberties of the people. Nonetheless, proponents of state aid, a loosely organized group centered in Tennessee Valley and eastern hill counties that stood to benefit most from projected routes for railroads, were confident that the governor would not defy the expressed will of the legislature if aid bills were passed. Previous Alabama governors had been reluctant to veto legislation and generally had done so only on technical, constitutional grounds. When differences emerged over policy issues, governors had usually deferred to the legislature. Thus, the state-aid men were genuinely surprised when Winston vetoed nearly all of the railroad bills they pushed through the legislature.

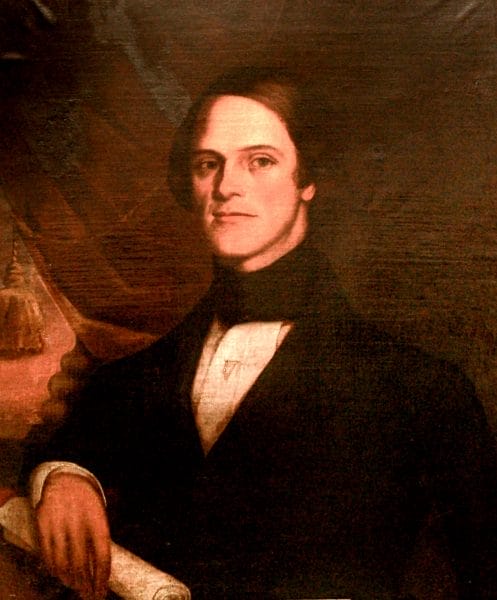

Alexander Beaufort Meek

The most significant legislation to pass during Winston’s first term was the Education Act of 1854, which began state aid for free public schools for white children. Sponsored by Mobile representative Alexander B. Meek and fashioned after Mobile County’s school system, the act provided for the state to divide $100,000 a year among the counties and allowed counties to collect real estate and personal property taxes for educational purposes. The act also created a state superintendent of education and was later amended to establish county superintendents. The state’s timing was unfortunate, and little progress was made before the Civil War began.

Alexander Beaufort Meek

The most significant legislation to pass during Winston’s first term was the Education Act of 1854, which began state aid for free public schools for white children. Sponsored by Mobile representative Alexander B. Meek and fashioned after Mobile County’s school system, the act provided for the state to divide $100,000 a year among the counties and allowed counties to collect real estate and personal property taxes for educational purposes. The act also created a state superintendent of education and was later amended to establish county superintendents. The state’s timing was unfortunate, and little progress was made before the Civil War began.

Winston’s stand against using public monies to subsidize private corporations was popular with the voters, most of whom were small farmers who wanted to keep taxes and state expenditures as low as possible. He easily won reelection in 1855. Indeed, more ballots were cast for him than for any antebellum governor of Alabama. A triumphant Winston told the legislature in November that he looked forward to restricting state government to the limited activities espoused by his supporters. The pro-railroad forces, however, redoubled their efforts in the legislature and passed a host of bills dealing with grants of corporate privilege and the lending of state funds. Winston vetoed most of these bills. Even when the legislature overturned some of his vetoes, he found ways to block the use of state funds for internal improvements.

Winston’s anti-corporate stand on behalf of the people’s money made him an undeniable popular hero, but it cost him the party support he needed to gain a U.S. Senate seat in 1857. By derailing the promotional agenda so obviously favored by the railroad and commercial interests in the Democratic Party, he had alienated key party supporters. These Democrats succeeded in keeping Winston out of the Senate, and in 1859 they pushed a railroad bill through the legislature that provided the general aid Winston had so staunchly opposed. Passage of this bill established a precedent for state aid to railroads that would be important during the Reconstruction Era.

Winston’s hope for a Senate seat was also damaged by the perception that he was not committed enough to southern rights to represent Alabama in the national legislature. He needed to strengthen his credentials as an advocate of southern rights if he hoped to win a seat in the Senate. Although he wanted his old enemy Yancey to look like the responsible person, it was Winston who actually caused the Alabama delegation to walk out of the 1860 Democratic Party convention in Charleston over the issue of slavery. He returned to Montgomery, where he made speeches accusing Yancey of having pursued a reckless course that split the party and insured the election of Lincoln. Yancey’s reputation suffered little. In fact, he became the man of the hour in Alabama when he led the state out of the Union. In the meantime, Winston had supported the candidacy of the northern Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, whose election he believed would save the Union. Winston miscalculated terribly, and his stand on behalf of cooperative action by the southern states was rejected at Alabama’s secession convention in favor of immediate and separate state secession.

Andrew Barry Moore

After serving as Gov. Andrew Moore‘s appointee as Alabama’s commissioner to Louisiana to consult on the secession crisis, Winston raised troops and fought in the Civil War as colonel of the Eighth Alabama Infantry. He saw action during the Virginia peninsula campaign in 1862, but poor health forced him to resign. After the war, he was a delegate to the state constitutional convention of 1865. Although he was elected finally to the U.S. Senate for the 1867-73 term, the Republican Congress refused to seat him when he refused to take the oath of allegiance to the United States. Committed to white supremacy, he remained a bitter enemy of Congressional Reconstruction until his death.

Andrew Barry Moore

After serving as Gov. Andrew Moore‘s appointee as Alabama’s commissioner to Louisiana to consult on the secession crisis, Winston raised troops and fought in the Civil War as colonel of the Eighth Alabama Infantry. He saw action during the Virginia peninsula campaign in 1862, but poor health forced him to resign. After the war, he was a delegate to the state constitutional convention of 1865. Although he was elected finally to the U.S. Senate for the 1867-73 term, the Republican Congress refused to seat him when he refused to take the oath of allegiance to the United States. Committed to white supremacy, he remained a bitter enemy of Congressional Reconstruction until his death.

Complications from rheumatoid arthritis contributed to his death in Mobile on December 21, 1871. By then, Alabama was in the midst of an ambitious and expensive program of state aid for railroads, a far cry from the limited role of state government championed by Winston during his tenure as governor. No other antebellum governor so forcefully voiced the fears of the people’s interests being corrupted by an alliance of public and corporate power. But John A. Winston’s vision of an agrarian Alabama bound by the strict states’ rights doctrines of Jacksonian democracy was now as much a relic of the past as the slave society he had so ardently defended.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Brewer, Willis. Alabama: Her History, Resources, War Record, and Public Men, from 1540 to 1872. Montgomery: Barrett and Brown, 1872.

- Garrett, William. Reminiscences of Public Men in Alabama for Thirty Years. Atlanta: Plantation Publishing, 1872.

- Thornton, J. Mills, III. Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800-1860. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978.