Russell M. Cunningham (1904-05)

Russell McWhortor Cunningham (1855-1921) is not given a number designation in the listing of Alabama governors because he merely filled the role during Gov. William D. Jelks‘s recurrent illnesses and recuperations out of state. A physician, Cunningham worked to improve the treatment and health of convicts who were leased by the state to mining companies and other industries.

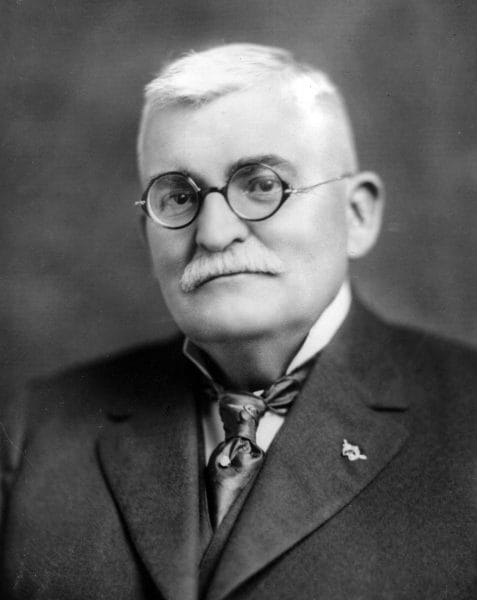

Russell M. Cunningham

Russell McWhortor Cunningham was born on August 25, 1855, in Mt. Hope, Lawrence County, to Moses W. Cunningham and Caroline Russell Cunningham. He received his education in the county public schools and at age 17 began working as a teacher and also as a farmer, employing skills he learned from his parents. With funds saved from his work, he began studying medicine with physician John M. Clark of north Alabama, attended the Louisville Medical College in 1874 and 1875, and completed his studies in medicine at Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York City in 1879. In 1876, he established a medical practice in Franklin County and married Sue L. Moore, with whom he had one son. After his first wife died, Cunningham married Annice Taylor of Birmingham.

Russell M. Cunningham

Russell McWhortor Cunningham was born on August 25, 1855, in Mt. Hope, Lawrence County, to Moses W. Cunningham and Caroline Russell Cunningham. He received his education in the county public schools and at age 17 began working as a teacher and also as a farmer, employing skills he learned from his parents. With funds saved from his work, he began studying medicine with physician John M. Clark of north Alabama, attended the Louisville Medical College in 1874 and 1875, and completed his studies in medicine at Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York City in 1879. In 1876, he established a medical practice in Franklin County and married Sue L. Moore, with whom he had one son. After his first wife died, Cunningham married Annice Taylor of Birmingham.

In his autobiography, Cunningham made no effort to disguise the fact that he entered the political arena as a way of furthering his medical career, although he also noted that he intended to serve the state to the best of his ability. He successfully ran as a Democratic candidate for the Alabama House of Representatives from Franklin County in 1880 and served during the 1880-81 session but did not seek reelection.

In 1881, Cunningham was appointed physician of the state penitentiary and moved to Wetumpka, where he also established a private practice. He began to compile the first reliable statistics on prison mortality rates in Alabama, and his recommendations concerning health, sanitation, and work hours reduced the death rate among Alabama convicts, who were leased to work in industry, from 18 percent per annum to 2.83 percent per annum by October 1884. In 1883, when prison reform legislation required him to establish his residence where most state convicts were employed, the Pratt mines, he moved to the Birmingham industrial district.

In 1885, he became physician and surgeon at the Pratt mines and at the Ensley division of the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company, the largest industrial concern in the district and one of the major leasers of convicts. He also became the company physician at the Alabama Steel and Ship Building Company, established a private infirmary at Ensley, served as a county health officer, and held numerous positions of leadership in local, state, and regional medical associations. In October 1894, he and eight other Birmingham physicians opened a private medical school in which he taught physical diagnosis and clinical medicine. The school in Birmingham set off a rivalry with the previously established public institution in Mobile, a competition that Birmingham ultimately won.

Also active in community affairs, Cunningham was president of the school board in Ensley and held numerous offices in Masonic organizations. In 1896, he re-entered politics, drafted by supporters of a silver standard for currency to run for the state Senate against a “gold standardist.” As such, he supported William Jennings Bryan, the pro-silver Democratic candidate for president. Although Cunningham claimed to be opposed by his own social and economic cohort, which he described as “the banks, the corporations, and the business interests generally,” he won the election and represented Jefferson County from 1896 to 1900, serving as president of the Senate in 1898. His activity in Democratic Party politics increased in 1900, when ill health made it impossible for William J. Samford to continue his speaking engagements. Cunningham was chosen by the State Democratic Executive Committee to fulfill those commitments.

Elected as a delegate to the 1901 constitutional convention, Cunningham helped to design the measures that disfranchised black voters in the state. Through speeches and editorials, Cunningham went to great lengths to justify his position. A white supremacist, he believed that blacks were an inferior race and that political equality would lead to partial social equality and interracial marriage.

William D. Jelks

The new constitution reestablished the office of lieutenant governor and extended the term of elected state officials from two to four years. In 1902, Cunningham ran for lieutenant governor on the Democratic ticket, supporting the gubernatorial candidacy of William D. Jelks, the incumbent governor. Cunningham and Jelks won easily both in the primary and in the general election. On April 25, 1904, when Jelks left the state to recuperate from tuberculosis, Cunningham took over his duties and served almost a year. While serving as governor, Cunningham attempted to bring greater regulation of railroad rates, an issue that had affected the 1902 election and would reemerge in the 1906 governor’s race. He assisted Jelks in devising reforms in the convict-lease system in what he thought were some of the “best works” of his public career. A member of the Committee on Temperance in the 1880s and a Baptist, Cunningham supported local option (whereby each county decides whether to support Prohibition), later campaigned for a statewide prohibition amendment and endorsed the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. On other issues, he expressed an interest in adequate funding for education and in fair and honest elections, and he actively pressed for safety and sanitation inspections of coal mines.

William D. Jelks

The new constitution reestablished the office of lieutenant governor and extended the term of elected state officials from two to four years. In 1902, Cunningham ran for lieutenant governor on the Democratic ticket, supporting the gubernatorial candidacy of William D. Jelks, the incumbent governor. Cunningham and Jelks won easily both in the primary and in the general election. On April 25, 1904, when Jelks left the state to recuperate from tuberculosis, Cunningham took over his duties and served almost a year. While serving as governor, Cunningham attempted to bring greater regulation of railroad rates, an issue that had affected the 1902 election and would reemerge in the 1906 governor’s race. He assisted Jelks in devising reforms in the convict-lease system in what he thought were some of the “best works” of his public career. A member of the Committee on Temperance in the 1880s and a Baptist, Cunningham supported local option (whereby each county decides whether to support Prohibition), later campaigned for a statewide prohibition amendment and endorsed the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. On other issues, he expressed an interest in adequate funding for education and in fair and honest elections, and he actively pressed for safety and sanitation inspections of coal mines.

Braxton Bragg Comer

Because the new constitution did not allow elected officials to succeed themselves, Cunningham was expected to be the next governor. He announced his candidacy for the Democratic nomination, but his hopes were not fulfilled. Braxton Bragg Comer, a businessman and textile-mill owner from Birmingham and the sole elected representative on the state’s railroad commission, seized on the regulation issue and announced his candidacy. In 1902, the State Democratic Executive Committee agreed to a direct primary for officials who were elected statewide. The Democratic primary would soon be the most important election held in Alabama, far more critical than the November election. Cunningham was backed by many of the leading newspapers in the state, whereas Comer enjoyed the support only of the Birmingham News. Although Cunningham was considered the candidate of the conservative wing of the party, his platform was, in many ways, as “progressive” as that of Comer, who wore that title. Cunningham praised Comer’s work on the railroad commission but reminded voters that he urged reform in that arena as well. Both candidates supported increased spending for education, pensions for the state’s Confederate veterans, and road improvements. Cunningham stressed the continuing need for reform of the convict-lease system, but Comer emphasized railroad regulation to the exclusion of almost all other issues.

Braxton Bragg Comer

Because the new constitution did not allow elected officials to succeed themselves, Cunningham was expected to be the next governor. He announced his candidacy for the Democratic nomination, but his hopes were not fulfilled. Braxton Bragg Comer, a businessman and textile-mill owner from Birmingham and the sole elected representative on the state’s railroad commission, seized on the regulation issue and announced his candidacy. In 1902, the State Democratic Executive Committee agreed to a direct primary for officials who were elected statewide. The Democratic primary would soon be the most important election held in Alabama, far more critical than the November election. Cunningham was backed by many of the leading newspapers in the state, whereas Comer enjoyed the support only of the Birmingham News. Although Cunningham was considered the candidate of the conservative wing of the party, his platform was, in many ways, as “progressive” as that of Comer, who wore that title. Cunningham praised Comer’s work on the railroad commission but reminded voters that he urged reform in that arena as well. Both candidates supported increased spending for education, pensions for the state’s Confederate veterans, and road improvements. Cunningham stressed the continuing need for reform of the convict-lease system, but Comer emphasized railroad regulation to the exclusion of almost all other issues.

In a contest that lasted almost a year, Cunningham spoke in every county in the state and held several debates with Comer. Cunningham favored a stronger child labor law than his opponent, and the Montgomery Advertiser attempted to discredit Comer by pointing out that he employed children in his Avondale textile mill. Even this charge failed to stem the rising popular support for Comer. Cunningham lost the Democratic nomination bid in August 1906, and a new era was launched in Alabama as Comer supporters also won a majority of seats in the state’s legislature.

Cunningham returned to his medical practice in Jefferson County and worked on the manuscript for his autobiography, in which he stated that losing the governor’s race was the best thing that could have happened to him. Cunningham died in Birmingham on June 6, 1921, and was interred at Elmwood Cemetery.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Cunningham, Russell M. “Address of Dr. R. M. Cunningham: Candidates for Governor to People of Alabama.” Cunningham File, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery.

- ———. Autobiography (typescript). Cunningham File, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery.

- ———. Historical Interpretation. Montgomery: Alabama Historical Society, reprint no. 30, 1905.

- Doster, James F. “Alabama’s Gubernatorial Election of 1906.” Alabama Review 8 (1955): 163-78.

- Holley, Howard I. The History of Medicine in Alabama. Birmingham: University of Alabama School of Medicine, 1982.