Alabama State University

Levi Watkins Learning Center

Alabama State University (ASU) is a historically black university (HBCU) located in Montgomery. In its early days, the school was instrumental in providing formal education for African Americans in Alabama. The school’s professors and students were a formidable force in challenging the city of Montgomery’s segregation laws by playing a major role in the city’s famous bus boycott and sit-in movement that sparked the civil rights movement in America. Alabama State University boasts an enrollment of more than 6,000 students and seven degree-granting colleges, schools, and divisions: College of Arts and Sciences, College of Business Administration, College of Education, College of Health Sciences, College of Visual and Performing Arts, Division of Aerospace Studies (Air Force ROTC), and School of Graduate Studies. The school’s sports teams are affiliated with the Southwestern Athletic Conference, and the school’s team name is the Hornets. The school’s board of trustee members are appointed by the governor and are confirmed by the state Alabama State Senate.

Levi Watkins Learning Center

Alabama State University (ASU) is a historically black university (HBCU) located in Montgomery. In its early days, the school was instrumental in providing formal education for African Americans in Alabama. The school’s professors and students were a formidable force in challenging the city of Montgomery’s segregation laws by playing a major role in the city’s famous bus boycott and sit-in movement that sparked the civil rights movement in America. Alabama State University boasts an enrollment of more than 6,000 students and seven degree-granting colleges, schools, and divisions: College of Arts and Sciences, College of Business Administration, College of Education, College of Health Sciences, College of Visual and Performing Arts, Division of Aerospace Studies (Air Force ROTC), and School of Graduate Studies. The school’s sports teams are affiliated with the Southwestern Athletic Conference, and the school’s team name is the Hornets. The school’s board of trustee members are appointed by the governor and are confirmed by the state Alabama State Senate.

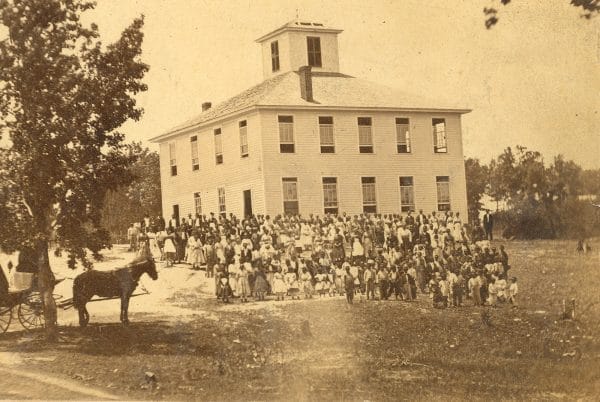

Lincoln Normal School

The forerunner of ASU, Lincoln Normal School, arose during Reconstruction under the auspices of a group of black Alabamians and the interracial American Missionary Association (AMA). The AMA was founded in 1846 by political abolitionists and members of the Liberty and the Free Soil parties. The group sent representatives to former Confederate states to educate blacks and set up schools for them after the end of the Civil War. In 1867, Thomas C. Steward, a white teacher from Ohio, along with H. F. Treadwell from Massachusetts and May Senderling from Maryland were sent by the AMA to help establish a school in Alabama for freedmen. Treadwell requested help from the Freedmen’s Bureau and its commissioner, Brig. Gen. Wager T. Swayne, agreed on the condition that the freedmen raise $500 and purchase the land needed for developing the school.

Lincoln Normal School

The forerunner of ASU, Lincoln Normal School, arose during Reconstruction under the auspices of a group of black Alabamians and the interracial American Missionary Association (AMA). The AMA was founded in 1846 by political abolitionists and members of the Liberty and the Free Soil parties. The group sent representatives to former Confederate states to educate blacks and set up schools for them after the end of the Civil War. In 1867, Thomas C. Steward, a white teacher from Ohio, along with H. F. Treadwell from Massachusetts and May Senderling from Maryland were sent by the AMA to help establish a school in Alabama for freedmen. Treadwell requested help from the Freedmen’s Bureau and its commissioner, Brig. Gen. Wager T. Swayne, agreed on the condition that the freedmen raise $500 and purchase the land needed for developing the school.

The group settled on a site in Marion, Perry County, and the town’s white citizens donated $250 to the building fund. The majority of the money to fund the school was raised by nine former slaves known as the “Marion Nine.” These men—Alexander H. Curtis, Joey Pinch, Thomas Speed, Thomas Lee, Nickolas Dale, James Childs, John Freeman, Nathan Levert, and David Harris—had been working to provide an education for the black children of Marion. Curtis was the driving force in the push for the school to be organized as the Lincoln Normal School, and on July 18, 1867, papers were filed with the probate judge of Perry County incorporating the Lincoln School in Marion.

Rosa Parks Monument at ASU

In 1868, the AMA leased a building in Marion and began operating the Lincoln Normal School. Initially, the school’s curriculum consisted of basic literacy and a classical curriculum for more advanced students that focused on Greek, Latin, mathematics, English, history, philosophy, biology, political science, and chemistry. In 1869, the AMA, the Freedmen’s Bureau, and Alabama freedmen raised $4,200 to construct a new building. In 1870, the state began its support of the institution with a small legislative appropriation of $486. State funding increased to $1,250 the following year, but the AMA still provided teachers. In November 1871, Peyton Finley, the first black member of the Alabama State Board of Education, presented two bills to establish four schools for the training of white teachers and four schools for the training of black teachers; they were approved the following month. The proposed locations for the black schools were in Montgomery, Sparta, Marion, and Huntsville, with each institution overseen by a board of commissioners.

Rosa Parks Monument at ASU

In 1868, the AMA leased a building in Marion and began operating the Lincoln Normal School. Initially, the school’s curriculum consisted of basic literacy and a classical curriculum for more advanced students that focused on Greek, Latin, mathematics, English, history, philosophy, biology, political science, and chemistry. In 1869, the AMA, the Freedmen’s Bureau, and Alabama freedmen raised $4,200 to construct a new building. In 1870, the state began its support of the institution with a small legislative appropriation of $486. State funding increased to $1,250 the following year, but the AMA still provided teachers. In November 1871, Peyton Finley, the first black member of the Alabama State Board of Education, presented two bills to establish four schools for the training of white teachers and four schools for the training of black teachers; they were approved the following month. The proposed locations for the black schools were in Montgomery, Sparta, Marion, and Huntsville, with each institution overseen by a board of commissioners.

In 1874, the institution’s first president, George N. Card, who was white, used state funds to reorganize Lincoln Normal School and thus established the State Normal School for Colored Students, the first state-supported educational institution for blacks. Card was appointed president as a condition of the school’s reorganization and in exchange for increased financial support from the state. The school remained in Marion for 13 years. In late 1886, a group of local whites petitioned to have the school removed after an altercation between white students from Howard College, also in Marion, and Black Lincoln students. In the petition, the group complained that the school was dissuading prospective white students from coming to Marion. The petition was received favorably by the legislature, which agreed in 1887 to fund an African American college or university anywhere but Marion. Options included Birmingham, Brewton, Mobile, and Selma. Notably in Birmingham and Selma, white residents voiced opposition to locating a Black normal school in those cities and were heeded. Ultimately, the school’s trustees chose Montgomery. The state legislature authorized the establishment of the Alabama Colored People’s University and allotted $10,000 for the purchase of land and the construction of buildings and an additional $7,500 annually for operating expenses. The Alabama Colored People’s University replaced the State Normal School after officials found a suitable location in Montgomery that was acceptable to whites. Blacks who wanted the school in Montgomery pledged $5,000, donated land, and arranged for the temporary use of some buildings. Within eight months after passage of the enabling legislation, the university opened in Montgomery at Beulah Baptist Church, with nine faculty members under the leadership of the school’s second president, William Burns Paterson, who was also white.

Opposition to the university arose from local whites and ironically from prominent African American leader and president of Tuskegee Institute, Booker T. Washington, who was concerned about the proximity of the new competitor to his school in Tuskegee. Paterson helped the school overcome the opposition of whites in Montgomery through networking, community organizing, and meetings with various influential black and white groups in Montgomery at Old Ship AME Zion Church and Dexter Avenue Baptist Church to build interest in the school. As a result of his efforts, the school began its first classes on October 3, 1887. Washington, however, never fully accepted the school’s presence. Although he was cordial with the school’s leadership after the its relocation to Montgomery, he viewed the school as competition for notoriety, influence, and donors.

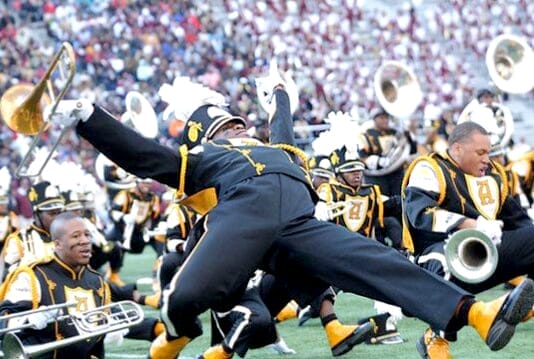

ASU Mighty Marching Hornets

Individuals who opposed state support of higher education for blacks successfully filed a suit in state court to impede the establishment of a college for blacks. In response, the Alabama Supreme Court repealed the legislation establishing support for a black university. For two years, the school operated on meager tuition fees, volunteers, and donations until the legislature reinstated its support in 1889. As a result of the lawsuit’s ruling, a hostile political atmosphere toward blacks, and the repeal of its college status, the school was renamed the Normal School for Colored Students and was thus stripped of its higher-education status. The school continued, however, erecting its first building in Montgomery in 1890. This structure burned in a suspicious fire in 1904 and was replaced in 1906 with a brick building. In the following decade, John William Beverly, the institution’s third leader and first African American president, and George W. Trenholm, the institution’s fourth president, organized the institution as a four-year teacher-training high school and added a junior college department. The school grew substantially in the 1920s with the acquisition of an 80-acre farm, and the state appropriated $50,000 to construct residence halls and dining facilities.

ASU Mighty Marching Hornets

Individuals who opposed state support of higher education for blacks successfully filed a suit in state court to impede the establishment of a college for blacks. In response, the Alabama Supreme Court repealed the legislation establishing support for a black university. For two years, the school operated on meager tuition fees, volunteers, and donations until the legislature reinstated its support in 1889. As a result of the lawsuit’s ruling, a hostile political atmosphere toward blacks, and the repeal of its college status, the school was renamed the Normal School for Colored Students and was thus stripped of its higher-education status. The school continued, however, erecting its first building in Montgomery in 1890. This structure burned in a suspicious fire in 1904 and was replaced in 1906 with a brick building. In the following decade, John William Beverly, the institution’s third leader and first African American president, and George W. Trenholm, the institution’s fourth president, organized the institution as a four-year teacher-training high school and added a junior college department. The school grew substantially in the 1920s with the acquisition of an 80-acre farm, and the state appropriated $50,000 to construct residence halls and dining facilities.

Montgomery Interpretive Center

The school was officially converted from a junior college to a four-year institution in 1928, and three years later it offered its first baccalaureate degrees in teacher education. Under the leadership of the school’s fifth president, Harper Councill Trenholm, the school petitioned the State Board of Education for a name change to reflect its growing mission. The state allowed the change, and in 1929 it became the State Teachers College, Alabama State College for Negroes. In 1935, the school was accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, but it is important to note that at the time the accrediting organization accredited black and white schools separately. Despite these positive changes, years of operating on meager funds and systemic racism made it difficult for ASU and other black schools to compete with their white counterparts and obtain accreditation. The school initially received a class “B” rating but in 1943 was raised to class “A,” the highest rating. The graduate division awarded its first master’s degree in 1943 and established branch campuses in Mobile and Birmingham.

Montgomery Interpretive Center

The school was officially converted from a junior college to a four-year institution in 1928, and three years later it offered its first baccalaureate degrees in teacher education. Under the leadership of the school’s fifth president, Harper Councill Trenholm, the school petitioned the State Board of Education for a name change to reflect its growing mission. The state allowed the change, and in 1929 it became the State Teachers College, Alabama State College for Negroes. In 1935, the school was accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, but it is important to note that at the time the accrediting organization accredited black and white schools separately. Despite these positive changes, years of operating on meager funds and systemic racism made it difficult for ASU and other black schools to compete with their white counterparts and obtain accreditation. The school initially received a class “B” rating but in 1943 was raised to class “A,” the highest rating. The graduate division awarded its first master’s degree in 1943 and established branch campuses in Mobile and Birmingham.

During the 1960s, the school experienced repercussions from the involvement of its students and faculty in the civil rights movement, notably in a sit-in at the Montgomery County Courthouse and subsequent related protests. State officials committed to segregation cut appropriations to the school, resulting in the loss of accreditation in 1961. The school regained its accreditation in 1966, however. In 1969, the State Board of Education approved the school for university status, and it became a comprehensive university. In 1975, the state legislature established an independent board of trustees for Alabama State University. Today, ASU is a state-supported comprehensive university located on an urban 172-acre campus. It offers associate’s, bachelor’s, master’s, doctoral degrees, and post-master’s certificates. In 2020, the National Park Service opened the Montgomery Interpretive Center as the third site on its Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail, joining the Selma Interpretive Center in Dallas County and the Lowndes Interpretive Center in Lowndes County.

Further Reading

- Caver, Joseph. “A Twenty-Year History of Alabama State University, 1867-1887.” Master’s thesis, Alabama State University, 1982.

- Caver, Joseph. From Marion to Montgomery: The Early Years of Alabama State University, 1867-1925. Montgomery, Ala.: New South Books, 2020.

- Watkins, Levi. Fighting Hard: The Alabama State University Experience. Detroit, Mich.: Harlo Press, 1987.

- Westhauser, Karl E., Elaine M. Smith, and Jennifer A. Fremlin, eds. Creating Community: Life and Learning at Montgomery’s Black University. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005.