Stars Fell on Alabama

Stars Fell on Alabama

Stars Fell on Alabama was written by Carl Lamson Carmer (1893-1976), who grew up in upstate New York. In it, Carmer relates his six years of living among the people and culture of Alabama in the 1920s. More than 70 years after its publication, students, scholars, and the general public still read the book and enjoy the stories that Carmer heard during his years in Alabama.

Stars Fell on Alabama

Stars Fell on Alabama was written by Carl Lamson Carmer (1893-1976), who grew up in upstate New York. In it, Carmer relates his six years of living among the people and culture of Alabama in the 1920s. More than 70 years after its publication, students, scholars, and the general public still read the book and enjoy the stories that Carmer heard during his years in Alabama.

As a boy, Carmer enjoyed history and folklore. He sat at his father’s feet and listened to stories that centered on the hills and hollows of the area around Dansville and Albion, where Willis Griswold Carmer was principal of the high schools. After Carl graduated from Albion High School, he earned an undergraduate degree in English at Hamilton College and then a master’s degree from Harvard University. After serving in the U.S. Army in World War I, he taught briefly at Syracuse University.

Stars Fell on Alabama

In 1921, he accepted a position teaching English at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa. Carmer discovered almost immediately upon settling in west Alabama that although he did not like some of the food, the people he met offered as many interesting stories as his father had. Among the most interesting was a Sumter County woman named Ruby Pickens Tartt, who related numerous tales she had heard from the rural African American tenant farmers in her home town of Livingston. Carmer quoted Tartt extensively in the book through a character called Mary Louise.

Stars Fell on Alabama

In 1921, he accepted a position teaching English at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa. Carmer discovered almost immediately upon settling in west Alabama that although he did not like some of the food, the people he met offered as many interesting stories as his father had. Among the most interesting was a Sumter County woman named Ruby Pickens Tartt, who related numerous tales she had heard from the rural African American tenant farmers in her home town of Livingston. Carmer quoted Tartt extensively in the book through a character called Mary Louise.

For six years, Carmer travelled to every corner of the state, kept copious notes, and later turned them into Stars Fell On Alabama, referring to an 1833 meteor event that appeared as a shower of stars falling on the countryside. Published by Farrar and Rinehart in 1934 and illustrated by LeRoy Baldridge, the story was so unusual that it defied conventional literary definition. It was part memoir, part history, and part cultural analysis. Today, it would likely fall into the category of creative non-fiction, similar to Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood.

His first section, “Tuscaloosa Nights,” describes his arrival in Tuscaloosa by train, his trip to his hotel, and a meeting with a fellow faculty member and an old friend from Harvard and several of his associates. Late that first night, another professor whom he immediately liked told him bluntly to get out of the state before it was too late. After, the echo of the man’s voice is heard in memory for six years. Carmer loves the place and enjoys the people, but he also is frightened of the people, place, and many of its customs.

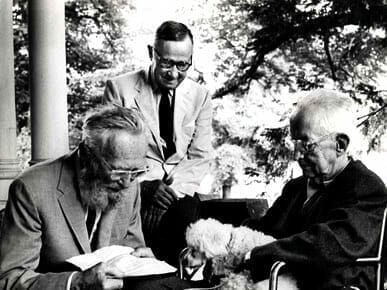

Edward Steichen, Carl Carmer, and Charles Sheeler

Given to judgmental generalities, Carmer writes as though he is an explorer in a foreign land. In one scene, after playing the golf course at the Tuscaloosa Country Club, he hears a haunting chant emanating from beyond a wall of bushes. He wanders down a little-used path and finds shanties and the black residents engaged in voodoo-style rituals and watches in fascination. He goes with a friend to witness a cross-burning by Ku Klux Klan members in white robes and hoods. He travels into the hill country and listens to fiddlers playing traditional tunes. Up on Sand Mountain, he attends an all-day singing with dinner-on-the-ground, witnesses foot-washing at a hard-shell Baptist church, where members believe so strongly in predestination that if a person is not chosen by God there is nothing he can do to save himself. As Carmer watched and recorded these events in his notebooks, he was deeply affected by what he saw and heard. He translated his experiences through the filter of his northern upbringing, and thereby created a strange, fascinating, interesting, and terrible world.

Edward Steichen, Carl Carmer, and Charles Sheeler

Given to judgmental generalities, Carmer writes as though he is an explorer in a foreign land. In one scene, after playing the golf course at the Tuscaloosa Country Club, he hears a haunting chant emanating from beyond a wall of bushes. He wanders down a little-used path and finds shanties and the black residents engaged in voodoo-style rituals and watches in fascination. He goes with a friend to witness a cross-burning by Ku Klux Klan members in white robes and hoods. He travels into the hill country and listens to fiddlers playing traditional tunes. Up on Sand Mountain, he attends an all-day singing with dinner-on-the-ground, witnesses foot-washing at a hard-shell Baptist church, where members believe so strongly in predestination that if a person is not chosen by God there is nothing he can do to save himself. As Carmer watched and recorded these events in his notebooks, he was deeply affected by what he saw and heard. He translated his experiences through the filter of his northern upbringing, and thereby created a strange, fascinating, interesting, and terrible world.

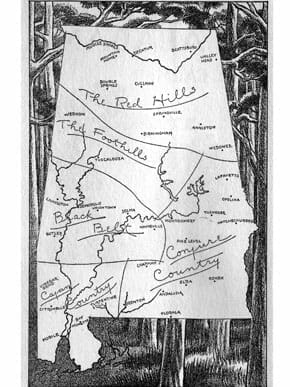

Red Hills in Stars Fell on Alabama

Soon after the book was published in 1934, it became a best seller. It was highly praised in the northern press, including the New York Times. Among Alabamians, however, many who read the book in the 1930s were shocked that Carmer would choose to write about such events as Ku Klux Klan parades, foot-washings, and voodoo rituals. Some Alabamians believed that he was mocking the state in his work and that he focused only on the negative aspects of Alabama culture. Despite this view, the book has been reprinted numerous times and remains important as a dramatized view of Alabama.

Red Hills in Stars Fell on Alabama

Soon after the book was published in 1934, it became a best seller. It was highly praised in the northern press, including the New York Times. Among Alabamians, however, many who read the book in the 1930s were shocked that Carmer would choose to write about such events as Ku Klux Klan parades, foot-washings, and voodoo rituals. Some Alabamians believed that he was mocking the state in his work and that he focused only on the negative aspects of Alabama culture. Despite this view, the book has been reprinted numerous times and remains important as a dramatized view of Alabama.

Throughout his life, Carmer was known as a superb regional writer of novels, including Listen for a Lonesome Drum, Dark Trees to the Wind, and Genesee Fever, all set in upstate New York during the American Revolution. Before his death in Bronxville, New York, on September 11, 1976, he divided his time between his home state and Sarasota, Florida. He served as president of the Author’s Guild, Poetry Society of America, and the American Center of P.E.N., the international society of writers and editors.

Additional Resources

Carmer, Carl. Stars Fell on Alabama. Introduction by J. Wayne Flynt. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1985.

Minor, David. “He Heard the Lonesome Drum.” Odds & Ends: A Newsletter of Eagles Byte Historical Research 17 (February 1997); http://home.eznet.net/O&E9702.html.