Modern Cotton Production in Alabama

Cotton is the primary row crop grown in Alabama, exceeding the individual acreages for corn, soybeans, peanuts, and wheat. Agricultural practices and technology developed since the mid-twentieth century, such as pest eradication measures and modern mechanical planters, harvesters, and balers, have enabled Alabama cotton farmers to increase their output on fewer and fewer acres. Cotton is grown in 59 of Alabama’s 67 counties. The top cotton-producing counties in Alabama are Limestone, Madison, Lawrence, Monroe, Colbert, and Escambia Counties and Alabama ranks ninth in cotton production.

Modern Cotton Production in Alabama

The level of cotton production in the post-Civil War era ranged from approximately 700,000 to 1.1 million bales between 1880 and 1900. In 2001, Alabama cotton farmers harvested 900,000 bales, but in 2006, that figure dropped to 675,000 bales. By 2019, however, Alabama’s cotton farmers had greatly increased production, harvesting some 1,028,000 bales. The number of acres cultivated has also changed over time. In 1880, some 2.5 million acres were planted in cotton, compared with roughly 540,000 acres in 2019. Modern production techniques and science-based practices have enabled the state to become more efficient in producing more fiber on fewer acres.

Modern Cotton Production in Alabama

The level of cotton production in the post-Civil War era ranged from approximately 700,000 to 1.1 million bales between 1880 and 1900. In 2001, Alabama cotton farmers harvested 900,000 bales, but in 2006, that figure dropped to 675,000 bales. By 2019, however, Alabama’s cotton farmers had greatly increased production, harvesting some 1,028,000 bales. The number of acres cultivated has also changed over time. In 1880, some 2.5 million acres were planted in cotton, compared with roughly 540,000 acres in 2019. Modern production techniques and science-based practices have enabled the state to become more efficient in producing more fiber on fewer acres.

Alabama farmers grow “upland cotton” (Gossypium hirsutum), a species that is native to Central America, Mexico, and the Caribbean and Gulf Coast regions. This species has a medium fiber length, is very strong, and is used largely by the apparel industry. Other types of cotton grown in the United States include Pima (Gossypium barbadense) and Acala (a relative of upland cotton), both of which produce a longer fiber that is softer to the touch than that of upland cotton and is preferred for finer, softer fabric. Most of the cotton grown in the United States, including Alabama, is exported, with China being the primary importer. In turn, workers in China, Mexico, and other countries spin the cotton into yarn, weave it into fabric in textile mills, and make clothing and other products such as towels, sheets, and bath cloths. Finished goods are shipped to the United States and other countries for purchase.

Limestone County Cotton

Modern farms are no longer subsistence-based, small-scale enterprises, as was common during the early history of the state. Today, they are efficient, profitable enterprises that use technology to farm large tracts of land. So although fewer acres are devoted to cotton production, the number of acres per farm has increased drastically. Approximately 50 percent of the cotton in the state is grown on farms of 2,000 acres or more, and 25 percent of the cotton farms range from 1,000 to 1,999 acres. Thus, 75 percent of the cotton acres reside on farms of 1,000 acres or larger, with most being locally owned.

Limestone County Cotton

Modern farms are no longer subsistence-based, small-scale enterprises, as was common during the early history of the state. Today, they are efficient, profitable enterprises that use technology to farm large tracts of land. So although fewer acres are devoted to cotton production, the number of acres per farm has increased drastically. Approximately 50 percent of the cotton in the state is grown on farms of 2,000 acres or more, and 25 percent of the cotton farms range from 1,000 to 1,999 acres. Thus, 75 percent of the cotton acres reside on farms of 1,000 acres or larger, with most being locally owned.

Cotton in Colbert County

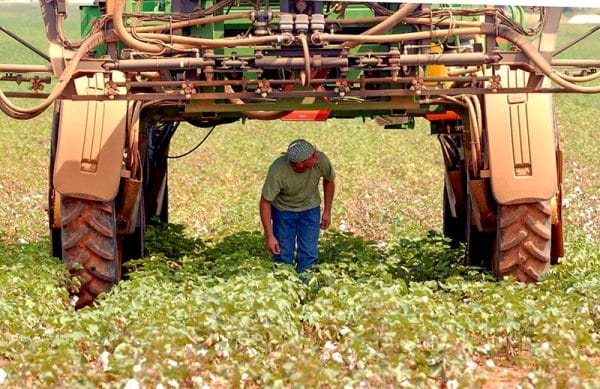

Modern equipment and technology have reduced the amount of manual labor employed in the cultivation and harvest of cotton. Today’s cotton producers must make a major capital investment to produce cotton. Not only is a high yield necessary to meet production costs, the high-quality fiber that is demanded by the mills requires high management costs as well. Tractors pull mechanical planters that can sow four to twelve rows with each pass across the field, enabling farmers to seed expansive acreages quickly in the spring. Farmers also employ large tractors and self-propelled sprayers to maintain the crops. Mechanical cotton pickers are able to harvest between two and six rows with each pass through the field. As the seed cotton is harvested, it is placed into machines known as module builders, which compress the cotton into a compact unit known as a module. Cotton modules are built in designated areas of the field and covered with tarpaulins to reduce damage from water and wind. Specially designed trucks pick up the modules in the field and deliver them to the gin for processing. Newly developed pickers, soon to be widely available, will harvest seed cotton and press it into small modules as the machine moves through the field. In turn, the small modules are hauled to the gin for processing. Cotton gins are generally located within 75 miles of the production fields to save on hauling expenses. Many of the cotton gins in the state are owned by individuals or by farmer cooperatives in which local producers operate in some type of partnership.

Cotton in Colbert County

Modern equipment and technology have reduced the amount of manual labor employed in the cultivation and harvest of cotton. Today’s cotton producers must make a major capital investment to produce cotton. Not only is a high yield necessary to meet production costs, the high-quality fiber that is demanded by the mills requires high management costs as well. Tractors pull mechanical planters that can sow four to twelve rows with each pass across the field, enabling farmers to seed expansive acreages quickly in the spring. Farmers also employ large tractors and self-propelled sprayers to maintain the crops. Mechanical cotton pickers are able to harvest between two and six rows with each pass through the field. As the seed cotton is harvested, it is placed into machines known as module builders, which compress the cotton into a compact unit known as a module. Cotton modules are built in designated areas of the field and covered with tarpaulins to reduce damage from water and wind. Specially designed trucks pick up the modules in the field and deliver them to the gin for processing. Newly developed pickers, soon to be widely available, will harvest seed cotton and press it into small modules as the machine moves through the field. In turn, the small modules are hauled to the gin for processing. Cotton gins are generally located within 75 miles of the production fields to save on hauling expenses. Many of the cotton gins in the state are owned by individuals or by farmer cooperatives in which local producers operate in some type of partnership.

Boll Weevil

Historically, particularly after the arrival of the boll weevil in 1910, cotton required intense pest-management efforts. The success of the boll weevil eradication program that took place throughout much of the twentieth century and the more recent introduction of genetically engineered “Bt” cotton varieties have reduced the amount of insecticides needed to control the pests. Bt cotton contains a toxin derived from Bacillus thuringiensis, a soil bacterium that produces a protein toxic to some insects, including the larvae of Heliothus worm species, including the tobacco budworm and cotton bollworm. The larvae eat the cotton leaf or other vegetative portion and die.

Boll Weevil

Historically, particularly after the arrival of the boll weevil in 1910, cotton required intense pest-management efforts. The success of the boll weevil eradication program that took place throughout much of the twentieth century and the more recent introduction of genetically engineered “Bt” cotton varieties have reduced the amount of insecticides needed to control the pests. Bt cotton contains a toxin derived from Bacillus thuringiensis, a soil bacterium that produces a protein toxic to some insects, including the larvae of Heliothus worm species, including the tobacco budworm and cotton bollworm. The larvae eat the cotton leaf or other vegetative portion and die.

Weed control in cotton is also now less labor intensive than at any other time. Cotton fields in Alabama are no longer hand-weeded or cultivated to control unwanted vegetation because new varieties have been developed that tolerate broad-spectrum herbicides. This allows producers to treat cotton fields with an herbicide called glyphosate, which is applied after the weeds germinate and emerge, without harming the crop. The growing season generally lasts from April or May through September, and cotton bolls mature and begin to open in the early fall in Alabama. When the bolls begin to open, the plants are treated with chemical defoliants that cause the leaves to fall off. The process allows mechanical pickers to easily harvest the white, fluffy seed cotton seen in the fields across the state during the fall.

Old Rotation Experiment Field

Modern cotton producers are also highly aware of environmental concerns and practice “conservation farming” techniques. These producers plant their row crops directly into an established cover crop without intensive tilling or plowing to prepare the seedbed. Most Alabama cotton producers plant rye and wheat and legumes, such as clover and vetch, in the fall as ground cover. These winter cover crops reduce soil crusting and erosion and increase the success for crop establishment and the amount of water available in the soil for plant growth.

Old Rotation Experiment Field

Modern cotton producers are also highly aware of environmental concerns and practice “conservation farming” techniques. These producers plant their row crops directly into an established cover crop without intensive tilling or plowing to prepare the seedbed. Most Alabama cotton producers plant rye and wheat and legumes, such as clover and vetch, in the fall as ground cover. These winter cover crops reduce soil crusting and erosion and increase the success for crop establishment and the amount of water available in the soil for plant growth.

Cotton’s benefits have resulted in a long history in row-crop operations across the state. Cotton provides producers with a cash crop that is consistent and relatively drought tolerant. Cotton is also an effective component of the crop rotation system that other crops, such as peanuts and soybeans. Cotton’s future in the agricultural landscape of Alabama remains bright and will likely be a major part of our farming for many more years.

Further Reading

- Burmester, C. “Cover Crops in Conservation Tillage.” In Cotton Production Guide, edited by C. Monks and M. Patterson. Auburn, Ala.: Alabama Cooperative Extension System Circular ANR-952, 1995; http://hubcap.clemson.edu/~blpprt/constill.html

- University of Tennessee. “Bt Cotton.” Knoxville: University of Tennessee, College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources, 2006; http://www.utextension.utk.edu/fieldCrops/cotton/cotton_insects/btcotton.htm

- Kelly, S., J. Barnett, D. Miller, and P. R. Vidrine. “Managing Roundup Ready Cotton.” Baton Rouge: Louisiana Cooperative Extension Service Publication 2838, 2001; http://www.lsuagcenter.com/NR/rdonlyres/0FB845AF-C636-4A1B-AB9E- 176EABCA530E/3277/pub2838glycotton2.pdf