Hobo Culture in Alabama

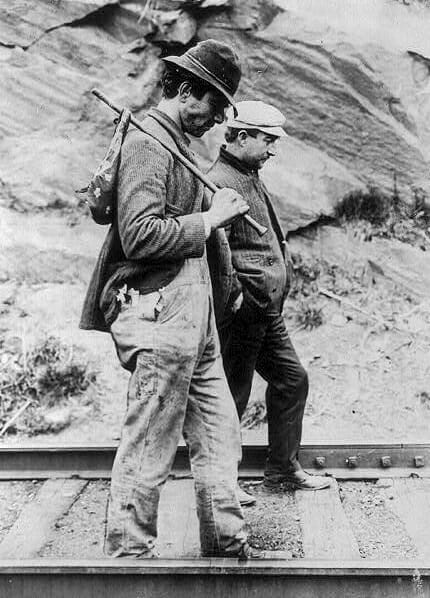

Hoboes Walking the Tracks

People referred to as hoboes were common throughout the United States from the 1870s through the 1930s. They were unskilled workers who traveled from place to place looking for work, commonly in railroad building and repair, bridge building and repair, and harvesting and cutting timber. Most of the work was seasonal or temporary. Hoboes usually traveled illegally in boxcars and in winter often returned to big cities, like Chicago or Minneapolis, where they stayed in cheap hotels and did jobs such as dishwashing. When traveling on the railroads, hoboes often stopped in towns where trains changed engines in camps that were known as “hobo jungles.” These encampments had agreed-upon rules, and most hoboes used road nicknames, known as “monikers,” such as “Boston Blackie” or “Chic (Chicago) Slim.” Historians do not know where the term “hobo” originated. Most were young men in their teens and twenties, but some were men who liked the freedom of the open road so much they traveled their whole lives. Most were white, and hoboes were most common in the Midwest and West.

Hoboes Walking the Tracks

People referred to as hoboes were common throughout the United States from the 1870s through the 1930s. They were unskilled workers who traveled from place to place looking for work, commonly in railroad building and repair, bridge building and repair, and harvesting and cutting timber. Most of the work was seasonal or temporary. Hoboes usually traveled illegally in boxcars and in winter often returned to big cities, like Chicago or Minneapolis, where they stayed in cheap hotels and did jobs such as dishwashing. When traveling on the railroads, hoboes often stopped in towns where trains changed engines in camps that were known as “hobo jungles.” These encampments had agreed-upon rules, and most hoboes used road nicknames, known as “monikers,” such as “Boston Blackie” or “Chic (Chicago) Slim.” Historians do not know where the term “hobo” originated. Most were young men in their teens and twenties, but some were men who liked the freedom of the open road so much they traveled their whole lives. Most were white, and hoboes were most common in the Midwest and West.

Hobo culture was present but not as fully developed in Alabama as it was outside of the Deep South because of hostile social attitudes and lower labor-force needs. However, post-Civil War laws to control black mobility formed the basis of the Tramp Laws, which were passed nationwide between 1876 and 1886 and which made it illegal to travel in search of work without having money. Furthermore, the 1931 Scottsboro trial of nine young black men accused of rape was the most notorious case involving hoboes in U.S. history and permanently fixed the image of Alabama as hostile to both blacks and hoboes.

Between 1865 and 1870, Alabama and other southern states enacted vagrancy laws that forced all freed persons to show they were gainfully employed by whites. At the same time, the convict-lease system arose, which consisted of renting the prisoners for their labor to industry or public-works projects. This system was largely based on the idea that blacks were criminal and that whites had the right to control black labor. However, because whites were also subject to prosecution under these laws, hoboes often avoided travelling in the South.

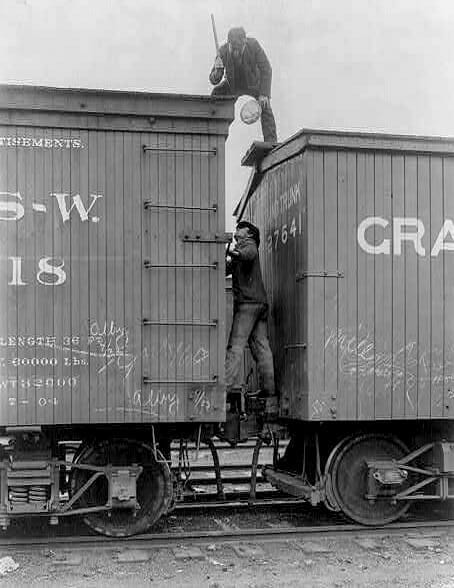

Railroad Worker and Hobo

To further control labor, between 1880 and 1882 Alabama also passed enticement laws that made it illegal to hire someone who was already employed. Whereas former Confederate soldiers typically could travel throughout the South on the “tramp” without fear of arrest, the entrenched localism and commitment to place in white southern culture created a heightened hostility to both black and “Yankee” tramps in Alabama. In general, the South produced fewer white vagabonds than the industrializing North because sharecropping tied workers down, and with few industrial jobs employers benefited because these landless people had so few other options. However, the gradual downgrading of “the tramp menace” to a mere nuisance did not happen below the Mason-Dixon Line. In 1903 the Alabama vagrancy law became even more severe, increasing fines from $10-$50 to $500, adding prison sentences of up to 6 months at hard labor, and requiring police to report potential vagrants to prosecutors for round-ups. From 1890 through the 1920s, Birmingham law enforcement periodically waged war on vagrants, often entering black saloons and arresting those who could not prove employment and leasing them to coal mines.

Railroad Worker and Hobo

To further control labor, between 1880 and 1882 Alabama also passed enticement laws that made it illegal to hire someone who was already employed. Whereas former Confederate soldiers typically could travel throughout the South on the “tramp” without fear of arrest, the entrenched localism and commitment to place in white southern culture created a heightened hostility to both black and “Yankee” tramps in Alabama. In general, the South produced fewer white vagabonds than the industrializing North because sharecropping tied workers down, and with few industrial jobs employers benefited because these landless people had so few other options. However, the gradual downgrading of “the tramp menace” to a mere nuisance did not happen below the Mason-Dixon Line. In 1903 the Alabama vagrancy law became even more severe, increasing fines from $10-$50 to $500, adding prison sentences of up to 6 months at hard labor, and requiring police to report potential vagrants to prosecutors for round-ups. From 1890 through the 1920s, Birmingham law enforcement periodically waged war on vagrants, often entering black saloons and arresting those who could not prove employment and leasing them to coal mines.

Attitudes toward hoboes generally became less hostile in the 1930s, when huge numbers of desperate unemployed workers began riding the rails, soon overwhelming railroad authorities. By 1932, 2,000 hoboes a month came through Birmingham, which was probably Alabama’s main gathering place. Most communities had no shelters, but Selma’s offer of one night’s lodging and two meals and insistence that hoboes move on was typical.

Nationally, hobo life was welcoming for African Americans, and most hobo jungles were integrated, although in the South blacks and whites were sometimes not allowed in the same boxcar. On March 25, 1931, in what appears to be a single incident of this type even in the South, white hoboes reported to the local sheriff that they had been forced off a train traveling from Chattanooga to Memphis in a brawl with black hoboes. When the train was stopped in Scottsboro, Alabama, two white women dressed in overalls were unexpectedly discovered on the train; they falsely accused nine young black men of rape. The Scottsboro convictions, retrials, and appeals remained notorious until the 1950s and fixed the image of hobo culture in Alabama in the public mind. There are few other cultural references in the hobo lifestyle to Alabama because it was considered such a hostile state. The increase in production during and after World War II largely made hoboes obsolete as a source of labor. When trains began using diesel engines in the 1950s, they became too difficult to ride illegally. Present-day homeless populations generally stay in one city and seek jobs or aid there, unlike the traveling hoboes of the past.

Additional Resources

Cohen, William. At Freedom’s Edge: Black Mobility and the Southern White Quest for Racial Control, 1861-1915. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1991.

Cresswell, Tim. The Tramp in America. London: Reaction Books, 2001.

Jones, Jacqueline. The Dispossessed: America’s Underclasses from the Civil War to the Present. New York: Basic Books, 1992.

Kusmer, Kenneth. Down and Out, On the Road: The Homeless in American History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.