Tuskegee University

White Hall at Tuskegee University

Tuskegee University, established in 1881 in Tuskegee, Macon County, is the second-oldest historically black college in Alabama. Many of its faculty and staff made significant contributions to agriculture and rural life, and the school served as the training ground for the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II fame. Tuskegee students and faculty were also involved in promoting civil rights for African Americans in the 1950s and 1960s. Tuskegee University offers 60 programs of study in five colleges, with a student enrollment of approximately 3,000 students. The campus consists of a 450-acre campus and an additional 4,500 acres of forest and agriculture experiment and research station space. Tuskegee has been ranked by U.S. News and World Report as the top historically black college in the state of Alabama and sixth nationally among historically black colleges and universities. For its connections to noted writers and alumni Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray, the university is a stop on the Southern Literary Trail.

White Hall at Tuskegee University

Tuskegee University, established in 1881 in Tuskegee, Macon County, is the second-oldest historically black college in Alabama. Many of its faculty and staff made significant contributions to agriculture and rural life, and the school served as the training ground for the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II fame. Tuskegee students and faculty were also involved in promoting civil rights for African Americans in the 1950s and 1960s. Tuskegee University offers 60 programs of study in five colleges, with a student enrollment of approximately 3,000 students. The campus consists of a 450-acre campus and an additional 4,500 acres of forest and agriculture experiment and research station space. Tuskegee has been ranked by U.S. News and World Report as the top historically black college in the state of Alabama and sixth nationally among historically black colleges and universities. For its connections to noted writers and alumni Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray, the university is a stop on the Southern Literary Trail.

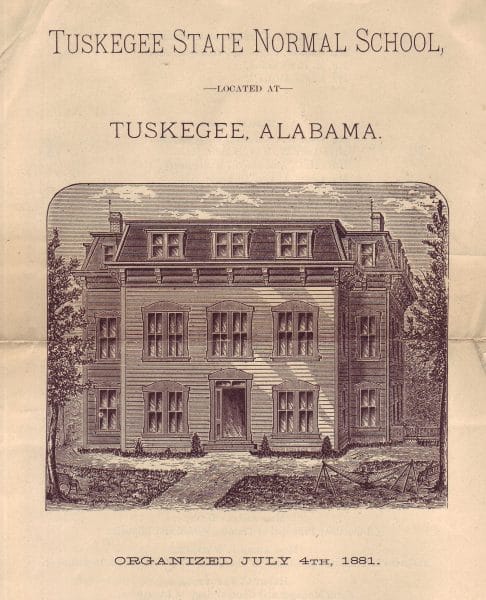

Tuskegee State Normal School

The school was founded on July 4, 1881, as the Tuskegee Normal School for Colored Teachers. Lewis Adams, an influential black leader and member of the Republican Negro Congress, suggested to Wilbur F. Foster, a white Democrat seeking re-election to the Alabama State Senate, that the development of a school for blacks in Macon County would win him black votes in the election. Foster won the office and delivered a bill to develop a normal school in Tuskegee that also allocated $2,000 annually to compensate teachers in Macon County. No funding was allocated for infrastructure, however. Adams, along with Thomas Dryer and M. B. Swanson, formed the school’s first board of commissioners, although Dryer was replaced early on. The new board immediately began a search for the school’s first faculty member and leader. Booker T. Washington, an instructor at Hampton Institute (present-day Hampton University) in Hampton, Virginia, accepted the challenge.

Tuskegee State Normal School

The school was founded on July 4, 1881, as the Tuskegee Normal School for Colored Teachers. Lewis Adams, an influential black leader and member of the Republican Negro Congress, suggested to Wilbur F. Foster, a white Democrat seeking re-election to the Alabama State Senate, that the development of a school for blacks in Macon County would win him black votes in the election. Foster won the office and delivered a bill to develop a normal school in Tuskegee that also allocated $2,000 annually to compensate teachers in Macon County. No funding was allocated for infrastructure, however. Adams, along with Thomas Dryer and M. B. Swanson, formed the school’s first board of commissioners, although Dryer was replaced early on. The new board immediately began a search for the school’s first faculty member and leader. Booker T. Washington, an instructor at Hampton Institute (present-day Hampton University) in Hampton, Virginia, accepted the challenge.

Washington had little to work with. With no money available to purchase instructional space, Washington used a room donated by Butler Chapel AME Zion Church to serve as a classroom for the school’s 30 adult students, most of whom came primarily from surrounding Macon County. Shortly thereafter, the university purchased a 100-acre abandoned plantation, near its original site, which still functions as the central part of the campus today. Washington used his talents and his social and political connections to help the university ascend to national prominence. That rise was not without controversy, however.

Booker T. Washington

Under Washington’s guidance, Tuskegee took a leadership role in the developing industrial education movement. In 1883, he hired English and social sciences teacher Adella Hunt Logan, who would go on to become a leader in the suffrage movement and the school’s first librarian. Washington also became an outspoken advocate for the movement at a time when there was a national debate among black intellectuals about the pros and cons of industrial versus liberal education. His most vocal opponent was W. E. B. Du Bois, a staunch supporter of liberal arts education. Washington’s persuasiveness won the support of many white philanthropic organizations that were integral to the creation of black colleges. He was such a successful fundraiser that the institution gained independence from the state of Alabama in 1892, becoming a private entity but retaining its status as a state land-grant college. In 1893, the state increased Tuskegee’s annual appropriation to $3,000, and the Slater Fund, a philanthropic organization, donated $1,000 for the development of an industrial education program. By this time, the school had grown to 600 students and 38 faculty members and had acquired an additional 1,300 acres of land, resulting in a 1,400-acre campus. The site included 20 buildings and had livestock, equipment, and property totaling $180,000.

Booker T. Washington

Under Washington’s guidance, Tuskegee took a leadership role in the developing industrial education movement. In 1883, he hired English and social sciences teacher Adella Hunt Logan, who would go on to become a leader in the suffrage movement and the school’s first librarian. Washington also became an outspoken advocate for the movement at a time when there was a national debate among black intellectuals about the pros and cons of industrial versus liberal education. His most vocal opponent was W. E. B. Du Bois, a staunch supporter of liberal arts education. Washington’s persuasiveness won the support of many white philanthropic organizations that were integral to the creation of black colleges. He was such a successful fundraiser that the institution gained independence from the state of Alabama in 1892, becoming a private entity but retaining its status as a state land-grant college. In 1893, the state increased Tuskegee’s annual appropriation to $3,000, and the Slater Fund, a philanthropic organization, donated $1,000 for the development of an industrial education program. By this time, the school had grown to 600 students and 38 faculty members and had acquired an additional 1,300 acres of land, resulting in a 1,400-acre campus. The site included 20 buildings and had livestock, equipment, and property totaling $180,000.

Tuskegee Institute Movable School

Tuskegee faculty were at the forefront of developing curriculum for the industrial education movement. As Tuskegee grew in size and importance so did the faculty, attracting such future luminaries as George Washington Carver. Carver, who arrived in 1896 to chair the agriculture department, would gain fame for many groundbreaking advances in the field of agriculture, including the introduction of crop rotation to Alabama’s rural farmers. Carver was also the guiding force behind the development of Tuskegee’s Movable School and a supporter of its facilitator, Thomas Monroe Campbell, who was the first black extension agent in the United States.

Tuskegee Institute Movable School

Tuskegee faculty were at the forefront of developing curriculum for the industrial education movement. As Tuskegee grew in size and importance so did the faculty, attracting such future luminaries as George Washington Carver. Carver, who arrived in 1896 to chair the agriculture department, would gain fame for many groundbreaking advances in the field of agriculture, including the introduction of crop rotation to Alabama’s rural farmers. Carver was also the guiding force behind the development of Tuskegee’s Movable School and a supporter of its facilitator, Thomas Monroe Campbell, who was the first black extension agent in the United States.

Robert R. Moton

Booker T. Washington remained president until his death in 1915. He was succeeded by Robert R. Moton, a former administrator at Hampton Institute, who served until 1935. After Washington’s death, the industrial education model at black colleges lost a significant amount of its momentum. At the time of Washington’s death, HBCUs had produced a thriving black middle class that sought greater control over the curriculum of black colleges. This new middle class was largely comprised of educators who recognized the value of a liberal arts education. Under Moton’s leadership, Tuskegee began to offer a liberal arts curriculum. During his tenure, Tuskegee donated land for the creation of the Tuskegee Veterans Administration Hospital in 1923 for black veterans of World War I. At the time, the hospital was the first and only such institution staffed by blacks. Administrator Bess Bolden Walcott and fellow members of the Tuskegee Women’s Club founded the first all-black Red Cross chapter at the institution, and she would later be instrumental in earning the organization a National Historic Landmark designation.

Robert R. Moton

Booker T. Washington remained president until his death in 1915. He was succeeded by Robert R. Moton, a former administrator at Hampton Institute, who served until 1935. After Washington’s death, the industrial education model at black colleges lost a significant amount of its momentum. At the time of Washington’s death, HBCUs had produced a thriving black middle class that sought greater control over the curriculum of black colleges. This new middle class was largely comprised of educators who recognized the value of a liberal arts education. Under Moton’s leadership, Tuskegee began to offer a liberal arts curriculum. During his tenure, Tuskegee donated land for the creation of the Tuskegee Veterans Administration Hospital in 1923 for black veterans of World War I. At the time, the hospital was the first and only such institution staffed by blacks. Administrator Bess Bolden Walcott and fellow members of the Tuskegee Women’s Club founded the first all-black Red Cross chapter at the institution, and she would later be instrumental in earning the organization a National Historic Landmark designation.

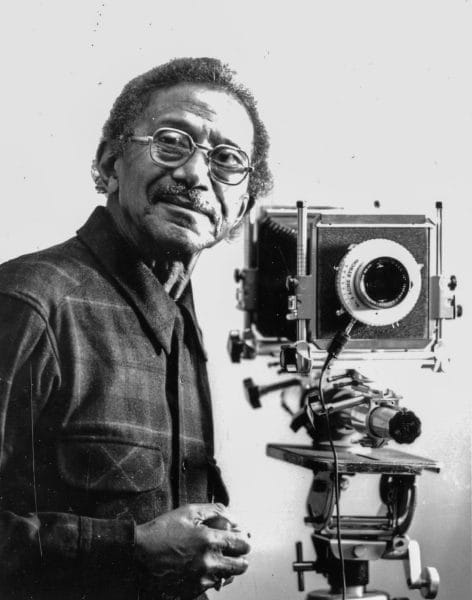

Prentice “P. H.” Polk

In 1935, Frederick D. Patterson, doctor of veterinary medicine and professor in Tuskegee’s department of agriculture, became the institute’s third president and served until 1953. Under his leadership, Tuskegee established the School of Veterinary Medicine, the only such program of its kind at a black college. To date, approximately 75 percent of all African American veterinarians in the United States were educated at Tuskegee. Patterson also founded the United Negro College Fund (UNCF), which has provided more than $1 billion in tuition assistance to students attending private HBCUs. Patterson envisioned the UNCF after realizing that the fundraising capabilities of private black colleges were stymied following World War II. He believed that those schools could be more effective in raising funds collectively, rather than individually soliciting prospective donors and philanthropic organizations. Twenty-six other black college presidents joined in his effort. Also during this period, Patterson hired Prentice Herman “P.H.” Polk as the institution’s official photographer; he would become one of the most noted names in the history of photography.

Prentice “P. H.” Polk

In 1935, Frederick D. Patterson, doctor of veterinary medicine and professor in Tuskegee’s department of agriculture, became the institute’s third president and served until 1953. Under his leadership, Tuskegee established the School of Veterinary Medicine, the only such program of its kind at a black college. To date, approximately 75 percent of all African American veterinarians in the United States were educated at Tuskegee. Patterson also founded the United Negro College Fund (UNCF), which has provided more than $1 billion in tuition assistance to students attending private HBCUs. Patterson envisioned the UNCF after realizing that the fundraising capabilities of private black colleges were stymied following World War II. He believed that those schools could be more effective in raising funds collectively, rather than individually soliciting prospective donors and philanthropic organizations. Twenty-six other black college presidents joined in his effort. Also during this period, Patterson hired Prentice Herman “P.H.” Polk as the institution’s official photographer; he would become one of the most noted names in the history of photography.

Moton Field

Not unlike Washington, Patterson’s visionary ideas were not without controversy. In November 1940, the War Department established a program to train black pilots for the U.S. Army Air Corps. Tuskegee was chosen as a training site for these pilots, given the institute’s existing course in aviation and its preexisting airfield, today named Moton Field in honor of the university’s second president. Tuskegee was once again criticized. Activists working to end racial segregation in the military opposed the creation of separate military training facilities. Nevertheless, Tuskegee moved forward with the training, and graduates of the program served with distinction in World War II. The pilots, now popularly known as the Tuskegee Airmen, were highly decorated for their service in the war and were critical forbears of the civil rights movement.

Moton Field

Not unlike Washington, Patterson’s visionary ideas were not without controversy. In November 1940, the War Department established a program to train black pilots for the U.S. Army Air Corps. Tuskegee was chosen as a training site for these pilots, given the institute’s existing course in aviation and its preexisting airfield, today named Moton Field in honor of the university’s second president. Tuskegee was once again criticized. Activists working to end racial segregation in the military opposed the creation of separate military training facilities. Nevertheless, Tuskegee moved forward with the training, and graduates of the program served with distinction in World War II. The pilots, now popularly known as the Tuskegee Airmen, were highly decorated for their service in the war and were critical forbears of the civil rights movement.

Samuel Younge Jr. at Tuskegee

In 1953, Luther H. Foster, who had previously served as the university’s business manager, succeeded Patterson. Foster led the institution through one of the most turbulent periods in U.S. history, the civil rights era of the 1950s and 1960s. Throughout his tenure and with his full support, students and professors were active in boycotts and court battles over black civil and voting rights. Tragically, Tuskegee student and voting-rights activist Samuel Younge Jr. was killed while attempting to use a whites-only restroom in 1966. That same year, Tuskegee became the first black college designated as a Registered National Historic Landmark. In 1966, noted social scientist and faculty member Lewis Wade Jones became director of the institute’s Rural Development Center, focusing on economic development for Black people in the rural South. In 1974, it became the only black college to be named a National Historic Site. During Foster’s tenure, the school established its College of Arts and Sciences and developed a number of engineering programs. He also eliminated a number of vocational programs. Gilbert L. Rochon, a research scientist and public health expert, became Tuskegee’s sixth president in November 2010. He served until 2014, when Brian Johnson, a literary scholar and academic administrator, was named as his replacement.

Samuel Younge Jr. at Tuskegee

In 1953, Luther H. Foster, who had previously served as the university’s business manager, succeeded Patterson. Foster led the institution through one of the most turbulent periods in U.S. history, the civil rights era of the 1950s and 1960s. Throughout his tenure and with his full support, students and professors were active in boycotts and court battles over black civil and voting rights. Tragically, Tuskegee student and voting-rights activist Samuel Younge Jr. was killed while attempting to use a whites-only restroom in 1966. That same year, Tuskegee became the first black college designated as a Registered National Historic Landmark. In 1966, noted social scientist and faculty member Lewis Wade Jones became director of the institute’s Rural Development Center, focusing on economic development for Black people in the rural South. In 1974, it became the only black college to be named a National Historic Site. During Foster’s tenure, the school established its College of Arts and Sciences and developed a number of engineering programs. He also eliminated a number of vocational programs. Gilbert L. Rochon, a research scientist and public health expert, became Tuskegee’s sixth president in November 2010. He served until 2014, when Brian Johnson, a literary scholar and academic administrator, was named as his replacement.

National Center for Bioethics, Tuskegee University

Long-time administrator Benjamin F. Payton became the fifth president in 1981. In 1985, the school changed its name from Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute to Tuskegee University. In addition, Payton oversaw the establishment of the Tuskegee University National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care, which took place in 1997 in the aftermath of the scandal surrounding the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. In addition, Tuskegee became the home of the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site in 1998. Under Payton’s leadership, the university created the General Daniel “Chappie” James Center for Aerospace Science and Health Education, the largest athletic arena in the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference. James was a Tuskegee alum, Tuskegee airman, and the first African American to attain the rank of four-star general. In the academic arena, Payton’s administration developed the College of Business and Information Science and introduced the only aerospace engineering program at an HBCU. The university also initiated its first doctoral programs, in integrative biosciences and materials science and engineering. In May 2018, university trustees named Lily D. McNair as the school’s eighth, and first woman, president. McNair has a doctorate in psychology from the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

National Center for Bioethics, Tuskegee University

Long-time administrator Benjamin F. Payton became the fifth president in 1981. In 1985, the school changed its name from Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute to Tuskegee University. In addition, Payton oversaw the establishment of the Tuskegee University National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care, which took place in 1997 in the aftermath of the scandal surrounding the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. In addition, Tuskegee became the home of the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site in 1998. Under Payton’s leadership, the university created the General Daniel “Chappie” James Center for Aerospace Science and Health Education, the largest athletic arena in the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference. James was a Tuskegee alum, Tuskegee airman, and the first African American to attain the rank of four-star general. In the academic arena, Payton’s administration developed the College of Business and Information Science and introduced the only aerospace engineering program at an HBCU. The university also initiated its first doctoral programs, in integrative biosciences and materials science and engineering. In May 2018, university trustees named Lily D. McNair as the school’s eighth, and first woman, president. McNair has a doctorate in psychology from the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

Booker T. Washington Monument

Tuskegee has had an undeniable impact on the evolution of black colleges. In addition to its academic developments, it was the first HBCU to have a marching band, which is a hallmark of the black college football season. The Tuskegee Golden Tigers are in the NCAA Division II and are members of the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference, which is comprised of 12 other HBCUs. The university was also vital in the development of intercollegiate activities at black colleges with the creation of golf and tennis tournaments. Most significantly Coach Cleve “Major” Abbott created the Tuskegee Relays in 1927, which was for many years the third largest track event in the country.

Booker T. Washington Monument

Tuskegee has had an undeniable impact on the evolution of black colleges. In addition to its academic developments, it was the first HBCU to have a marching band, which is a hallmark of the black college football season. The Tuskegee Golden Tigers are in the NCAA Division II and are members of the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference, which is comprised of 12 other HBCUs. The university was also vital in the development of intercollegiate activities at black colleges with the creation of golf and tennis tournaments. Most significantly Coach Cleve “Major” Abbott created the Tuskegee Relays in 1927, which was for many years the third largest track event in the country.

Prominent Tuskegee alumni include Daniel “Chappie” James, who graduated in 1942, talk-show host Tom Joyner, who was born in Tuskegee and earned a sociology degree at the institute, and the members of the Motown group the Commodores, which was formed by Tuskegee students Lionel Richie, Thomas McClary, Walter Orange, Ronald LaPread, Milan Williams, and William King.

Further Reading

- Brown II, M. Christopher, and Kassie Freeman. Black Colleges: New Perspectives on Policy and Practice. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2004.

- Drewry, Henry N., and Humphrey Doermann. Stand and Prosper: Private Black Colleges and Their Stories. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- Williams, Juan, and Dwayne Ashley. I’ll Find a Way or Make One: A Tribute to Historically Black Colleges and Universities. New York: HarperCollins, 2004.