Juliette Hampton Morgan

Juliette Hampton Morgan

Juliette Hampton Morgan (1914-1957), a Montgomery librarian, was among a small group of white liberal southerners who advocated racial justice in the 1940s and 1950s, a time of great social and political upheaval in Alabama. In letters to the Montgomery Advertiser, essays, and private correspondence with friends, family members, and colleagues, Morgan made some of the most insightful observations in the historical record about Montgomery’s racial crises. She wrote as a seventh-generation southerner, not as an outsider, and her work to end racial segregation came at a high cost.

Juliette Hampton Morgan

Juliette Hampton Morgan (1914-1957), a Montgomery librarian, was among a small group of white liberal southerners who advocated racial justice in the 1940s and 1950s, a time of great social and political upheaval in Alabama. In letters to the Montgomery Advertiser, essays, and private correspondence with friends, family members, and colleagues, Morgan made some of the most insightful observations in the historical record about Montgomery’s racial crises. She wrote as a seventh-generation southerner, not as an outsider, and her work to end racial segregation came at a high cost.

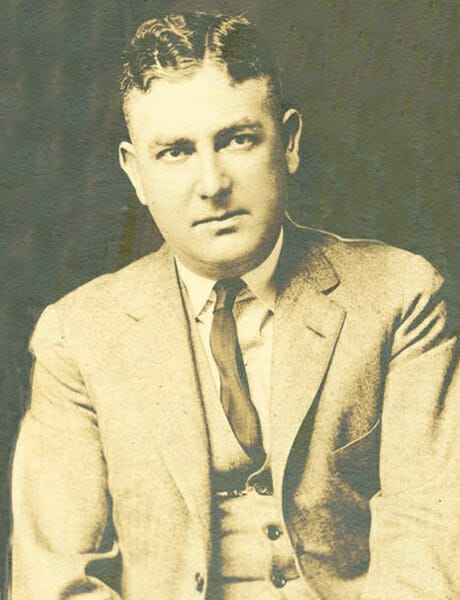

An unlikely activist, Morgan was born in Montgomery on February 21, 1914, to Lila Bess Olin Morgan, a descendent of Confederate general and South Carolina governor Wade Hampton, and Frank Perryman Morgan, grandson of a Georgia state senator and eldest son of the first mayor of Heflin, Cleburne County. In 1938, Frank Morgan unsuccessfully sought the Democratic nomination for governor of Alabama.

Frank P. Morgan

Morgan graduated from Montgomery’s Sidney Lanier High School in 1930 and earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English from the University of Alabama. In Tuscaloosa, she witnessed the ravages of the Great Depression. Many desperate residents—black and white—lost their jobs, their homes, and their savings, and no federal assistance was available to them. When she returned to Montgomery in 1936, Morgan became a supporter of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal economic reforms. She joined the local Democratic Club and participated in letter-writing campaigns to support federal anti-lynching legislation and to abolish the poll tax. She also volunteered with activist groups such as the Fellowship of the Concerned, the Southern Conference Educational Fund, and the Alabama Council on Human Relations. Morgan taught English and drama at Lanier until 1942, when she accepted a position as an assistant librarian at the local Carnegie Library. Ten years later, she was appointed research superintendent of the Montgomery City-County Public Library.

Frank P. Morgan

Morgan graduated from Montgomery’s Sidney Lanier High School in 1930 and earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English from the University of Alabama. In Tuscaloosa, she witnessed the ravages of the Great Depression. Many desperate residents—black and white—lost their jobs, their homes, and their savings, and no federal assistance was available to them. When she returned to Montgomery in 1936, Morgan became a supporter of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal economic reforms. She joined the local Democratic Club and participated in letter-writing campaigns to support federal anti-lynching legislation and to abolish the poll tax. She also volunteered with activist groups such as the Fellowship of the Concerned, the Southern Conference Educational Fund, and the Alabama Council on Human Relations. Morgan taught English and drama at Lanier until 1942, when she accepted a position as an assistant librarian at the local Carnegie Library. Ten years later, she was appointed research superintendent of the Montgomery City-County Public Library.

In 1946, Morgan’s involvement with a Montgomery interracial women’s prayer group brought her to an even more activist phase of her life. The prayer meetings had to be scheduled in black churches because no white congregation would risk hosting an integrated gathering, which violated the city’s municipal code. After participating in the group, she began to put her convictions into action on the city buses. For years she had witnessed white bus drivers mistreat black men and women who paid the same 10-cent fare that she did. Although Morgan had been raised to accept the principles of white supremacy, she was outraged when she saw drivers refuse to pick black people up in the rain, throw their change on the floor rather than hand it to them, and call them ugly names.

It was unusual for someone like Morgan, who came from a prominent family, to use the city buses. Many of Montgomery’s white residents drove to work, but she was unable to drive because she suffered from panic attacks. The fact that she used public transportation sensitized her to situations that many of her white friends, neighbors, and colleagues never experienced.

Juliette Hampton Morgan Memorial Library

One evening on her way home from the library, Morgan watched a black woman pay her fare and leave the bus to enter by the back door, as black people were required to do. Before the woman could re-enter, however, the driver pulled away. Morgan had seen actions like this before, but this evening she jumped up and pulled the emergency cord. When the bus stopped, she demanded that the driver open the back door and let the woman board. For the next several years, she disrupted service every time she witnessed an abuse. In 1952, three years before the start of the city’s famous bus boycott, she wrote a letter to the Montgomery Advertiser warning white residents that African Americans were tired of remaining silent about Montgomery’s segregation statutes and that things had to change.

Juliette Hampton Morgan Memorial Library

One evening on her way home from the library, Morgan watched a black woman pay her fare and leave the bus to enter by the back door, as black people were required to do. Before the woman could re-enter, however, the driver pulled away. Morgan had seen actions like this before, but this evening she jumped up and pulled the emergency cord. When the bus stopped, she demanded that the driver open the back door and let the woman board. For the next several years, she disrupted service every time she witnessed an abuse. In 1952, three years before the start of the city’s famous bus boycott, she wrote a letter to the Montgomery Advertiser warning white residents that African Americans were tired of remaining silent about Montgomery’s segregation statutes and that things had to change.

Morgan’s activism eventually threatened her position at the library. Her critiques of the city’s segregation laws outraged many white residents, including some of her own friends, neighbors, and colleagues. A few were so angry that they questioned her sanity. Former students, members of her church, shopkeepers, and people she had known all her life began to shun her. Under mounting pressure, Montgomery mayor William A. Gayle urged the library’s board of trustees to fire her. Although they refused, the library director warned Morgan not to write any more provocative letters.

Morgan agreed, but she was sorely tempted on February 3, 1956, when white students at the University of Alabama (UA), her alma mater, rioted after a Birmingham federal court ordered the school to register Autherine Lucy as its first black student. The terrified university trustees subsequently expelled Lucy, and for the next year crosses were burned all over the city to discourage other black students from applying to UA.

A year later, on January 5, 1957, Buford Boone, editor of the Tuscaloosa News, addressed a meeting of Tuscaloosa’s White Citizens’ Council and implored the leaders to stop supporting the violence. The complete text of his speech was published in the Tuscaloosa News, and Morgan finally broke her silence and wrote him a congratulatory note. With her permission, he published it. Her letter outraged Montgomery’s own White Citizens’ Council. A furious Mayor Gayle, a WCC member himself, vowed to remove her from the library. But the library trustees remained steadfast in their decision that firing Juliette Morgan would violate her First Amendment right of free speech. Their support provoked fury, and many white residents tore up their cards and boycotted the library. On July 15, 1957, someone burned a cross on Morgan’s front lawn. She resigned the following day and that night apparently took her own life with an overdose of sleeping pills.

The large number of people who attended her funeral service on July 17 demonstrated the remorse felt by Montgomery residents. Many who had refused to support Morgan while she lived, and several who had shunned and criticized her, came to pay their respects. Five years later, on August 13, 1962, the Montgomery public library was peacefully integrated.

On March 3, 2005, Juliette Hampton Morgan was inducted into the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame in Marion, and eight months later the City-County Library Board and the Montgomery County Commission voted unanimously to name the capital city’s central branch on High Street the Juliette Hampton Morgan Memorial Library.

Additional Resources

Lila Bess Olin Morgan Family Papers, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama.

Stanton, Mary. Journey Toward Justice: Juliette Hampton Morgan and the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2006.