Willie Mae "Big Mama" Thornton

Thorton, Willie Mae

Willie Mae Thornton (1926-1984) was an influential African American blues singer and songwriter whose career extended from the 1940s to the early 1980s. She was called “Big Mama” for both her size and her robust, powerful voice. She is best known for her gutsy 1952 rhythm and blues recording of “Hound Dog,” later covered by Elvis Presley, and for her original song “Ball and Chain,” made famous by Janis Joplin. Thornton’s compositions include more than 20 blues songs.

Thorton, Willie Mae

Willie Mae Thornton (1926-1984) was an influential African American blues singer and songwriter whose career extended from the 1940s to the early 1980s. She was called “Big Mama” for both her size and her robust, powerful voice. She is best known for her gutsy 1952 rhythm and blues recording of “Hound Dog,” later covered by Elvis Presley, and for her original song “Ball and Chain,” made famous by Janis Joplin. Thornton’s compositions include more than 20 blues songs.

Willie Mae Thornton was born December 11, 1926, to Thomas H. Thornton and Edna M. Richardson Thornton. She was one of at least four siblings. Several sources indicate she was born on the rural outskirts of Montgomery, but a few indicate the unincorporated community of Ariton in Dale County. By the time she was three, the family had settled in Lauderdale County. Her father was a minister and her mother sang in the church choir, and Willie Mae grew up singing in church and learned drums and harmonica, perhaps from a brother who was an outstanding player, later known as “Harp” Thornton.

Willie Mae’s mother died when she was 14, and she took a job cleaning a local saloon and soon was substituting for the regular singer. Accounts of how she attracted the notice of Atlanta music promoter Sammy Green vary. In one version, he heard her win first prize in a local amateur contest; in another she helped his artists move a piano up the club stairs. In any event, in 1941 Thornton joined Green’s Georgia-based show, The Hot Harlem Revue, and remained with him for seven years. Billed as the “New Bessie Smith,” she sang and danced throughout the southeastern United States. She later acknowledged the influence of artists heard during this time, including Smith, Ma Rainey, Junior Parker, and Memphis Minnie.

In 1948, Thornton left the Revue and settled in Houston, where she would contribute to the development of the “Texas blues” style. In this period, she worked with two producers: bandleader Johnny Otis and, most significant, a flamboyant black entrepreneur named Don Robey. Robey reportedly heard Thornton in Houston’s El Dorado Ballroom and was impressed with her ability to play multiple instruments, rare for a female singer. He signed her to a five-year contract with his Peacock Records Label. (This independent studio, later called Duke-Peacock, was known for gritty rhythm and blues and gospel and was an important influence on soul music and rock and featured artists such as Marie Adams, Johnny Ace, and a young Little Richard.)

Thornton’s open lesbianism caused some tension with Robey, but he produced her first recordings and set up a regular performance schedule for her in his Houston club, The Bronze Peacock, and on the southern performance trail known as the “Chitlin’ Circuit.” This string of clubs and venues covered the eastern and southern United States and were considered safe for African American musicians to play in. They ranged from the Cotton Club in New York’s Harlem neighborhood to local juke joints in Mississippi. Thornton spent much of the early 1950s on the road or recording for Robey or Johnny Otis when in Houston or Los Angeles.

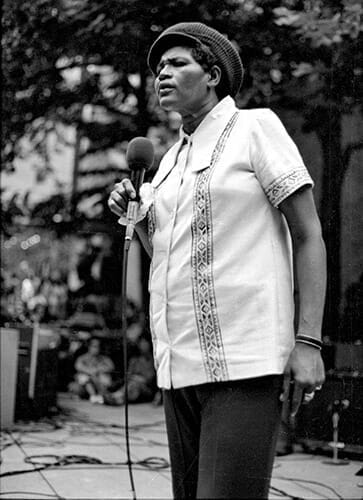

Willie Mae Thornton Performs in New York City

In 1952, Thornton travelled to New York City with the Otis Show to play the famed Apollo Theatre, where she initially served as the opening act for R&B artists “Little” Esther Phillips and Mel Walker but soon was promoted to headliner. She first earned the nickname “Big Mama” at this time. In August, at a recording session in southwest Los Angeles, she was approached by the young songwriting team of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller—soon to become rock & roll legends. They offered her a 12-bar blues vocal called “Hound Dog,” which she liked and paired on a single with her own “They Call Me Big Mama” on the B-side. Her exuberant “Hound Dog,” laden with open sexual references, whoops, and barks, was released nationwide in 1953 and soon topped the R&B charts. Despite its sale of two million copies, Thornton received only $500. In contrast, Elvis Presley’s 1956 version, heavily refined for mainstream audiences, brought him both fame and considerable financial reward. This is perhaps the most notorious example of the inequity that often existed when a black original was covered by a white artist.

Willie Mae Thornton Performs in New York City

In 1952, Thornton travelled to New York City with the Otis Show to play the famed Apollo Theatre, where she initially served as the opening act for R&B artists “Little” Esther Phillips and Mel Walker but soon was promoted to headliner. She first earned the nickname “Big Mama” at this time. In August, at a recording session in southwest Los Angeles, she was approached by the young songwriting team of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller—soon to become rock & roll legends. They offered her a 12-bar blues vocal called “Hound Dog,” which she liked and paired on a single with her own “They Call Me Big Mama” on the B-side. Her exuberant “Hound Dog,” laden with open sexual references, whoops, and barks, was released nationwide in 1953 and soon topped the R&B charts. Despite its sale of two million copies, Thornton received only $500. In contrast, Elvis Presley’s 1956 version, heavily refined for mainstream audiences, brought him both fame and considerable financial reward. This is perhaps the most notorious example of the inequity that often existed when a black original was covered by a white artist.

Rhythm & blues were soon eclipsed by the growth of rock & roll, and Thornton’s career slowed in the mid-1950s, although she was only in her thirties. Her agreements with both Robey and Otis expired, and in the late 1950s, she moved to San Francisco to perform with her old friend Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, a former Duke-Peacock artist. She had no contract or regular band and endured a number of difficult years. Fortunately, traditional blues were revived by the mid-1960s through the enthusiastic interest of artists such as Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, and the Rolling Stones, and the Bay Area became a center of blues activity. Although she still did not have regular support, Thornton always was invited to the Monterey Jazz Festival and in 1965 toured Europe with the American Folk Blues Festival, an unusual honor for a female artist.

In the late 1960s, she made several seminal recordings for Chris Strachwitz, producer of Arhoolie Records, including Big Mama Thornton: In Europe (1966), backed by Buddy Guy, Walter Horton, and Freddy Below; Big Mama Thornton with the Chicago Blues Band (1966), with Muddy Waters, Sam “Lightnin'” Hopkins, and Otis Spann; and Ball & Chain (1968), a compilation of original work by Thornton, Hopkins, and Larry Williams. Rock artists took note of these powerful recordings. The title song of Ball & Chain became a signature song for Thornton’s great admirer Janis Joplin, and in September 1968 Thornton appeared at the Sky River Rock Festival with a lineup that included the Grateful Dead, James Cotton, and Santana.

The 1970s brought more documentation of her work: Saved (Pentagram Records), She’s Back (Backbeat), and Jail and Sassy Mama! (Vanguard). Also at this time, however, years of heavy drinking began to affect Thornton’s health. She had to be led to the bandstand at the 1979 San Francisco Blues Festival, and despite illness gave a stunning performance. She survived a serious auto accident and rallied to perform at the 1983 Newport Jazz Festival with Muddy Waters, B. B. King, and Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson, resulting in a live recording, The Blues—A Real Summit Meeting (Buddha Records). Thornton’s final compilation, Quit Snoopin’ Round My Door, was released posthumously by Ace Records (U.K.). Willie Mae Thornton died of a heart attack in Los Angeles on July 25, 1984, at the age of 57. The funeral was led by her old friend, now Reverend Johnny Otis, and many artists paid tribute. She was buried in Inglewood Park Cemetery in Los Angeles. That same year, she was inducted into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame. She was inducted into the Alabama Music Hall of Fame in 2020.

Additional Resources

Dicaire, David. Blues Singers: Biographies of 50 Legendary Artists of the Early 20th Century. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland Press, 1999.

Grattan, Virginia. American Women Songwriters: A Biographical Dictionary. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 1993.

Smith, Jesse Carney, ed. Powerful Black Women. Detroit: Visible Ink Press, 1996.