Montgomery Bus Boycott

Rosa Parks’s Symbolic Bus Ride, 1956

Made famous by Rosa Parks‘s refusal to give her seat to a white man, the Montgomery bus boycott was one of the defining events of the civil rights movement. Beginning in 1955, the 13-month nonviolent protest by the black citizens of Montgomery to desegregate the city’s public bus system, Montgomery City Lines. Its success led to a November 1956 Supreme Court decision overturning segregated transportation that was legalized by the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling, an area left untouched by the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas decision to desegregate public schools.

Rosa Parks’s Symbolic Bus Ride, 1956

Made famous by Rosa Parks‘s refusal to give her seat to a white man, the Montgomery bus boycott was one of the defining events of the civil rights movement. Beginning in 1955, the 13-month nonviolent protest by the black citizens of Montgomery to desegregate the city’s public bus system, Montgomery City Lines. Its success led to a November 1956 Supreme Court decision overturning segregated transportation that was legalized by the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling, an area left untouched by the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas decision to desegregate public schools.

Jo Ann Robinson

Montgomery’s black residents had prepared the ground for the bus boycott long in advance; many had boycotted the buses on their own, or threatened to do so. In 1949, the newly formed Women’s Political Council (WPC) of Montgomery, an activist group of black professional women, began organizing the black community and lobbying white officials to modify Jim Crow restrictions in public transportation, with little success. In May 1954, WPC president Jo Ann Robinson, an English professor at Alabama State College, warned the mayor in a letter that a bus boycott might be imminent.

Jo Ann Robinson

Montgomery’s black residents had prepared the ground for the bus boycott long in advance; many had boycotted the buses on their own, or threatened to do so. In 1949, the newly formed Women’s Political Council (WPC) of Montgomery, an activist group of black professional women, began organizing the black community and lobbying white officials to modify Jim Crow restrictions in public transportation, with little success. In May 1954, WPC president Jo Ann Robinson, an English professor at Alabama State College, warned the mayor in a letter that a bus boycott might be imminent.

In March 1955, Claudette Colvin, a 15-year-old high school junior, refused to give up her bus seat to a white person. She was arrested for violating the segregated seating ordinances and mistreated by police. This angered the black community and sparked a brief, informal boycott of buses by many black residents. In August, Montgomery’s black community was shaken by the brutal lynching of 14-year-old Chicago native Emmett Till in Mississippi. Two months later, 18-year-old Mary Louise Smith, a house maid, was arrested for refusing to give up her seat. African Americans in Montgomery felt beleaguered.

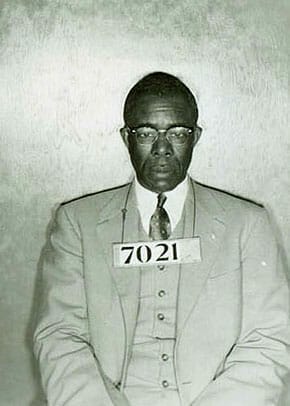

E. D. Nixon

In the early evening of December 1, 1955, Rosa L. Parks finished her work as a tailor’s assistant at Montgomery’s largest department store. She and her husband Raymond had been civil rights activists for years. Rosa Parks served as secretary of the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) branch and as advisor to the NAACP youth council, which Colvin joined after her arrest. When the bus driver, whom Parks had defied years before, ordered her to give up her seat for a white man, she replied “no.” Like Colvin and Smith, she was sitting in the unreserved midsection, and no vacant seat was free, so she would have had to stand while carrying her Christmas packages.

E. D. Nixon

In the early evening of December 1, 1955, Rosa L. Parks finished her work as a tailor’s assistant at Montgomery’s largest department store. She and her husband Raymond had been civil rights activists for years. Rosa Parks served as secretary of the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) branch and as advisor to the NAACP youth council, which Colvin joined after her arrest. When the bus driver, whom Parks had defied years before, ordered her to give up her seat for a white man, she replied “no.” Like Colvin and Smith, she was sitting in the unreserved midsection, and no vacant seat was free, so she would have had to stand while carrying her Christmas packages.

Although Parks did not plan her calm, determined protest, she recalled that she had a life history of rebelling against racial mistreatment. She believed that she had been “pushed as far as [she] could stand to be pushed.” Parks was arrested and then bailed out that night by friend E. D. Nixon, a Pullman car porter who had headed the local and Alabama state branches of the NAACP, and by two white friends, attorney Clifford Durr and his activist wife, Virginia Durr. The Durrs and Nixon persuaded Parks to allow her arrest to be used as a test case for the constitutionality of bus segregation.

Martin Luther King and Bus Boycott Organizers

When WPC president Robinson heard about Parks’s arrest later that evening, she decided that the time had come for the long-considered boycott. Robinson and two students stayed up all night at the college mimeographing 50,000 flyers that called for a one-day bus boycott on Monday, December 5, the day of Parks’s trial. The next day they distributed the flyers all over the city. After Robinson persuaded Nixon to support the effort, he phoned Montgomery’s black ministers to enlist their aid. After initial hesitation, Baptist preacher Martin Luther King Jr., who had been selected pastor of Montgomery’s middle-class Dexter Avenue Baptist Church the previous year, agreed to participate. Fellow Baptist minister Ralph Abernathy, who became King’s close friend and confidant, joined eagerly and served as the most effective boycott mobilizer after King.

Martin Luther King and Bus Boycott Organizers

When WPC president Robinson heard about Parks’s arrest later that evening, she decided that the time had come for the long-considered boycott. Robinson and two students stayed up all night at the college mimeographing 50,000 flyers that called for a one-day bus boycott on Monday, December 5, the day of Parks’s trial. The next day they distributed the flyers all over the city. After Robinson persuaded Nixon to support the effort, he phoned Montgomery’s black ministers to enlist their aid. After initial hesitation, Baptist preacher Martin Luther King Jr., who had been selected pastor of Montgomery’s middle-class Dexter Avenue Baptist Church the previous year, agreed to participate. Fellow Baptist minister Ralph Abernathy, who became King’s close friend and confidant, joined eagerly and served as the most effective boycott mobilizer after King.

Fred Gray

On Monday morning, December 5, 1955, few African Americans rode buses. Most walked to work or school, carpooled with friends, took taxis, or hitchhiked. Parks was convicted of violating the segregation law and fined $14. Her young lawyer, Fred Gray, appealed the ruling. That afternoon, black leaders created the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to run the bus protest and unexpectedly elected King as MIA president. That night, King gave a powerful speech to several thousand people assembled for the first of many MIA mass meetings held in black churches. The participants voted overwhelmingly to continue the protest until officials met their demands for fairer treatment.

Fred Gray

On Monday morning, December 5, 1955, few African Americans rode buses. Most walked to work or school, carpooled with friends, took taxis, or hitchhiked. Parks was convicted of violating the segregation law and fined $14. Her young lawyer, Fred Gray, appealed the ruling. That afternoon, black leaders created the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to run the bus protest and unexpectedly elected King as MIA president. That night, King gave a powerful speech to several thousand people assembled for the first of many MIA mass meetings held in black churches. The participants voted overwhelmingly to continue the protest until officials met their demands for fairer treatment.

At the outset white officials and opinion leaders believed that the bus boycott would collapse quickly and that blacks were not capable of a long-term protest campaign. The white community solidified in opposition, spurred by growth of the local White Citizens’ Council, but a few brave white citizens, such as Virginia and Clifford Durr and city librarian Juliette Hampton Morgan, supported the civil rights effort.

Montgomery Bus Boycott

The bus boycott carried on, supported by virtually all of Montgomery’s 40,000 black residents (more than one-third of the city population). Activist and cook Georgia Gilmore organized the “Club from Nowhere,” a group of women who cooked and sold food to raise money for the boycott and also accepted anonymous donations, and she also fed boycotters and movement leaders in her Montgomery home. The MIA created a highly efficient carpool system managed by women leaders, one of many vital roles that women performed. City officials negotiated with MIA leaders, who had initiated talks in late December 1955. The officials made no concessions, however, and talks broke down in January. When it became evident that the boycott would continue indefinitely, and that the bus company (which supported an end to segregated seating) might be put out of business, the city commissioners adopted a “get tough” policy. Police harassed carpool drivers, and King was arrested on a false speeding charge. His house was bombed while his wife, Coretta, and infant daughter were at home, but they were unharmed. Nixon’s home was also bombed, with little damage. (Later in the year, Abernathy’s church and other churches and parsonages were bombed.)

Montgomery Bus Boycott

The bus boycott carried on, supported by virtually all of Montgomery’s 40,000 black residents (more than one-third of the city population). Activist and cook Georgia Gilmore organized the “Club from Nowhere,” a group of women who cooked and sold food to raise money for the boycott and also accepted anonymous donations, and she also fed boycotters and movement leaders in her Montgomery home. The MIA created a highly efficient carpool system managed by women leaders, one of many vital roles that women performed. City officials negotiated with MIA leaders, who had initiated talks in late December 1955. The officials made no concessions, however, and talks broke down in January. When it became evident that the boycott would continue indefinitely, and that the bus company (which supported an end to segregated seating) might be put out of business, the city commissioners adopted a “get tough” policy. Police harassed carpool drivers, and King was arrested on a false speeding charge. His house was bombed while his wife, Coretta, and infant daughter were at home, but they were unharmed. Nixon’s home was also bombed, with little damage. (Later in the year, Abernathy’s church and other churches and parsonages were bombed.)

Rosa Parks Fingerprinted

On January 30, MIA leaders decided that because the city government would not accept their moderate demands, they would challenge the constitutionality of bus segregation—no longer seeking its reform but its abolition. For technical reasons, Parks’s case could not serve this purpose, so attorney Fred Gray filed a federal lawsuit on behalf of four female plaintiffs: Claudette Colvin, Mary Louise Smith, Aurelia Browder, and Susan McDonald. Meanwhile, in one of a string of blunders, city leaders indicted nearly 100 boycott leaders on conspiracy charges under an old anti-union law. They prosecuted King first, and his trial and conviction in March 1956 brought negative national publicity to the city as well as support and funds for the cause.

Rosa Parks Fingerprinted

On January 30, MIA leaders decided that because the city government would not accept their moderate demands, they would challenge the constitutionality of bus segregation—no longer seeking its reform but its abolition. For technical reasons, Parks’s case could not serve this purpose, so attorney Fred Gray filed a federal lawsuit on behalf of four female plaintiffs: Claudette Colvin, Mary Louise Smith, Aurelia Browder, and Susan McDonald. Meanwhile, in one of a string of blunders, city leaders indicted nearly 100 boycott leaders on conspiracy charges under an old anti-union law. They prosecuted King first, and his trial and conviction in March 1956 brought negative national publicity to the city as well as support and funds for the cause.

In June 1956, halfway through the boycott, the federal court in Montgomery ruled in Browder v. Gayle that Alabama’s bus segregation laws, both city and state, violated the Fourteenth Amendment and were thus unconstitutional. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld that decision in November, and MIA members voted to end the boycott. At the same moment, the city’s belated injunction shut down the carpool system by making it illegal, but those who had driven joined those who had been walking all along. After the city government lost its final appeal in the Supreme Court, black citizens desegregated Montgomery’s buses on December 21, 1956. White extremists fired on buses and bombed churches, but the year-long bus protest ended in victory over the city’s Jim Crow laws.

Posey Parking Lot Marker Unveiling

The triumphant bus boycott galvanized King and other southern preachers and activists like Abernathy and Fred Shuttlesworth of Birmingham to create the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which would initiate protests against white supremacy throughout the South. In this and other ways, the bus boycott prepared the ground for the historic black freedom movement that transformed American politics, culture, and values. The bus boycott forged the strategies and methods, the support networks and alliances, the language, vision, and spiritual expression that generated the ensuing mass movement for racial justice. The Montgomery experience showed the power of mass nonviolent direct action and set the standard for a democratic grassroots movement in which leadership was shared widely.

Posey Parking Lot Marker Unveiling

The triumphant bus boycott galvanized King and other southern preachers and activists like Abernathy and Fred Shuttlesworth of Birmingham to create the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which would initiate protests against white supremacy throughout the South. In this and other ways, the bus boycott prepared the ground for the historic black freedom movement that transformed American politics, culture, and values. The bus boycott forged the strategies and methods, the support networks and alliances, the language, vision, and spiritual expression that generated the ensuing mass movement for racial justice. The Montgomery experience showed the power of mass nonviolent direct action and set the standard for a democratic grassroots movement in which leadership was shared widely.

Additional Resources

Boycott. DVD, directed by Clark Johnson. Los Angeles: Home Box Office, Inc., 2001.

Burns, Stewart, ed. Daybreak of Freedom: The Montgomery Bus Boycott. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Eyes on the Prize: Awakenings (1954-1956). DVD, directed by Henry Hampton. Boston: Blackside, 1987.

Gray, Fred D. Bus Ride to Justice. Montgomery: Black Belt Press, 1994.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. Stride Toward Freedom. New York: Harper, 1958.

Robinson, Jo Ann Gibson. The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1987.

Thornton, J. Mills III. Dividing Lines. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.