Vulcan Statue and Vulcan Park

Vulcan Statue and Park

The statue of Vulcan looks down over the city of Birmingham from a height of almost 600 feet, watching over the city it was built to symbolize. The 56-foot, 60-ton statue is the largest iron figure ever cast, and at the time it was made, it was the biggest statue created in the United States and the second-tallest statue in the country, behind the Statue of Liberty. Conceived for the 1904 World’s Fair, the statue was cast with iron made from ore mined at Red Mountain, on which it now rests, in an effort to advertise Birmingham and promote Alabama’s iron industry.

Vulcan Statue and Park

The statue of Vulcan looks down over the city of Birmingham from a height of almost 600 feet, watching over the city it was built to symbolize. The 56-foot, 60-ton statue is the largest iron figure ever cast, and at the time it was made, it was the biggest statue created in the United States and the second-tallest statue in the country, behind the Statue of Liberty. Conceived for the 1904 World’s Fair, the statue was cast with iron made from ore mined at Red Mountain, on which it now rests, in an effort to advertise Birmingham and promote Alabama’s iron industry.

In Roman mythology, Vulcan was the god of fire and blacksmithing and the counterpart of the Greek god Hephaestus. Born to Jupiter and Juno, he was the builder of palaces and weapons for gods and demi-gods. Birmingham’s association with Vulcan dates to the 1880s, a time when Alabama was the nation’s fourth-highest producer of iron and steel, fueled by the area’s rich coal, limestone, and ore deposits, and Birmingham was expanding rapidly as a result. The image of Vulcan was assimilated into a short-lived Mardi Gras tradition from 1896–1900, in which the king of the celebration masqueraded as “Rex Vulcan,” or King Vulcan.

In 1903, a lack of funds derailed the state government’s plans to present an exhibit at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri. The Commercial Club of Birmingham (now the Birmingham Area Chamber of Commerce) took on the task of creating an exhibit under the leadership of club president Frederick M. Jackson and state fair director J. A. MacKnight, who conceived the idea of a giant iron man. The Commercial Club approved the project in October 1903, although opinions differed over whether to sculpt an “ugly” Vulcan or a “handsome” Mercury, the Roman god of commerce and travel. Ultimately, the blacksmith god was chosen to showcase Birmingham’s industrial might.

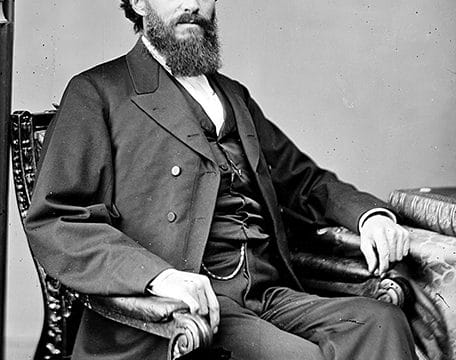

Giuseppe Moretti and Vulcan Statue, 1904

The club first called for the figure to rise 50 feet, then increased the height six feet to surpass a 52-foot bronze Buddha in Tokyo. With 2,000 square feet reserved at the Palace of Mines and Metallurgy on the St. Louis fairgrounds, MacKnight commissioned Italian sculptor Giuseppe Moretti, whose credentials included works for the Austro-Hungarian emperor, the city of Pittsburgh, and American industrialist William K. Vanderbilt. Moretti agreed to complete a plaster cast in 40 days, as the World’s Fair opening day loomed on April 30, 1904. Working in New Jersey, Moretti designed Vulcan standing next to an anvil, holding aloft a spear point in his right hand and a hammer in his left. He created an eight-foot clay prototype of his vision, and in January 1904, he and 16 assistants began work on full-sized plaster casts, which were transported to Birmingham by train, the last section arriving on March 8. The figure was cast from pig iron at Sloss Furnaces between March 10 and April 16 at Birmingham Steel and Iron Company, under the direction of Moretti and company president James R. McWane.

Giuseppe Moretti and Vulcan Statue, 1904

The club first called for the figure to rise 50 feet, then increased the height six feet to surpass a 52-foot bronze Buddha in Tokyo. With 2,000 square feet reserved at the Palace of Mines and Metallurgy on the St. Louis fairgrounds, MacKnight commissioned Italian sculptor Giuseppe Moretti, whose credentials included works for the Austro-Hungarian emperor, the city of Pittsburgh, and American industrialist William K. Vanderbilt. Moretti agreed to complete a plaster cast in 40 days, as the World’s Fair opening day loomed on April 30, 1904. Working in New Jersey, Moretti designed Vulcan standing next to an anvil, holding aloft a spear point in his right hand and a hammer in his left. He created an eight-foot clay prototype of his vision, and in January 1904, he and 16 assistants began work on full-sized plaster casts, which were transported to Birmingham by train, the last section arriving on March 8. The figure was cast from pig iron at Sloss Furnaces between March 10 and April 16 at Birmingham Steel and Iron Company, under the direction of Moretti and company president James R. McWane.

During the casting and molding process, members of the Commercial Club’s Vulcan Committee raised funds by assembling the plaster cast. It was the first time Vulcan was raised in its entirety, and the club charged 10 cents to view it and sold 12-inch bronze replicas. Another promotion took place when the minor-league Birmingham Barons baseball team hosted the New York Giants for three exhibition games. The third game fell on what was coined “Vulcan Day,” a fundraising effort in which the Barons took on the name “the Iron Men” for the day and Giants star pitcher Joe “Iron Man” McGinnity thrilled the crowd.

Vulcan in St. Louis

The first sections of the metal statue began their journey to St. Louis on April 18, but the final piece did not arrive until mid-May. Nevertheless, the partially constructed Vulcan was a crowd favorite. It was fully assembled and dedicated on June 7 and christened with Cahaba River water in place of champagne. The figure won a grand prize in September, and Moretti, McWane, and MacKnight were awarded silver medals for their efforts. City officials from St. Louis and San Francisco sought to purchase the colossus, the latter intent on employing it as a West Coast version of the Statue of Liberty. Birmingham rejected the offers, and in February 1905 the statue was taken apart and shipped home, where it was unloaded in a field on Red Mountain. Various civic groups argued over the statue’s future, and many Birmingham residents reacted negatively to its appearance, rejecting the Commercial Club’s proposal to display it downtown in Capitol Park (now Linn Park). The club finally approved a site for the statue at the 1906 Alabama State Fair, and workers in their haste bolted on the right arm incorrectly, so that the hand could not hold the spear point. Vulcan remained at the fair grounds until the 1930s and was adorned with advertisements for such products as Coca Cola and Liberty Overalls.

Vulcan in St. Louis

The first sections of the metal statue began their journey to St. Louis on April 18, but the final piece did not arrive until mid-May. Nevertheless, the partially constructed Vulcan was a crowd favorite. It was fully assembled and dedicated on June 7 and christened with Cahaba River water in place of champagne. The figure won a grand prize in September, and Moretti, McWane, and MacKnight were awarded silver medals for their efforts. City officials from St. Louis and San Francisco sought to purchase the colossus, the latter intent on employing it as a West Coast version of the Statue of Liberty. Birmingham rejected the offers, and in February 1905 the statue was taken apart and shipped home, where it was unloaded in a field on Red Mountain. Various civic groups argued over the statue’s future, and many Birmingham residents reacted negatively to its appearance, rejecting the Commercial Club’s proposal to display it downtown in Capitol Park (now Linn Park). The club finally approved a site for the statue at the 1906 Alabama State Fair, and workers in their haste bolted on the right arm incorrectly, so that the hand could not hold the spear point. Vulcan remained at the fair grounds until the 1930s and was adorned with advertisements for such products as Coca Cola and Liberty Overalls.

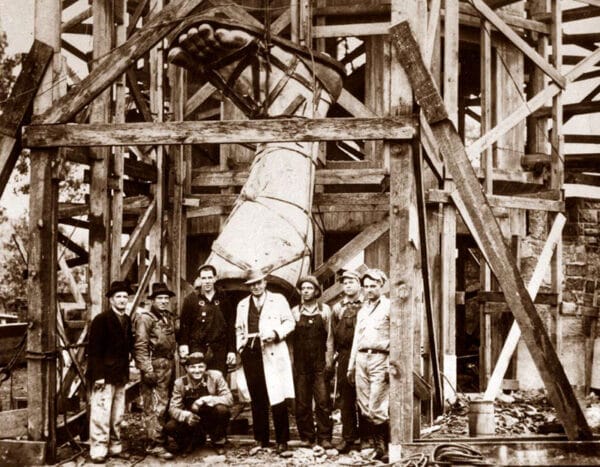

Statue of Vulcan

In 1935, a Birmingham committee led by the Kiwanis Club successfully convinced the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a Depression-era federal agency founded to create employment, to move Vulcan to a site on Red Mountain that the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company sold to the city for $5.00. The WPA provided the bulk of the funding for the project, and in 1936 Vulcan Park was built, including a museum and a 124-foot pedestal with an open-air observation platform. The statue was fully assembled on its new perch in May 1937, and in May 1939 Vulcan Park was completed, with a museum and cascading pools gracing the south side of the mountain. In 1946, the Birmingham Junior Chamber of Commerce replaced the spear point with a cone-shaped neon light that glowed green if the city had not seen a traffic fatality and red if it had.

Statue of Vulcan

In 1935, a Birmingham committee led by the Kiwanis Club successfully convinced the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a Depression-era federal agency founded to create employment, to move Vulcan to a site on Red Mountain that the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company sold to the city for $5.00. The WPA provided the bulk of the funding for the project, and in 1936 Vulcan Park was built, including a museum and a 124-foot pedestal with an open-air observation platform. The statue was fully assembled on its new perch in May 1937, and in May 1939 Vulcan Park was completed, with a museum and cascading pools gracing the south side of the mountain. In 1946, the Birmingham Junior Chamber of Commerce replaced the spear point with a cone-shaped neon light that glowed green if the city had not seen a traffic fatality and red if it had.

After the statue was installed on Red Mountain, cracks developed as a the result of the differential expansion rates of the metal and the concrete that was poured into the hollow cavity in the 1930s. Water also had entered the statue through an opening in the head and caused rust. The statue was repaired in the 1960s, and in 1971 the city painted Vulcan the color of iron ore, widened the pedestal, and enclosed the observation deck. The Vulcan Park Foundation was founded in 1999 to undertake a major renovation of the park and statue. After repairs and some recasting by Robinson Iron in Alexander City, the statue was painted gray and the pedestal was restored to approximate its original appearance. The park and museum reopened in 2004 to provide a sweeping view of the city and to educate visitors on the Vulcan statue’s significance in Birmingham history.

Additional Resources

Caton, Bill. Vulcan: Rekindling the Flame. Birmingham, Ala.: Hand Made Books, 1999.

Kiwanis International. The Story of Vulcan. Birmingham, Ala.: Birmingham Publishing, 1938.

Rowell, Raymond J. Vulcan In Birmingham: The Story of the World’s Largest “Iron Man,” and the City that Gave Him “Life.” Birmingham, Ala.: Birmingham Park & Recreation Board, 1972.

Thompson, George Clinton. “Vulcan: Birmingham’s Man of Iron.” Alabama Heritage 20 (Spring 1991): 2-17.