Knights of Labor in Alabama

Knights of Labor Meeting

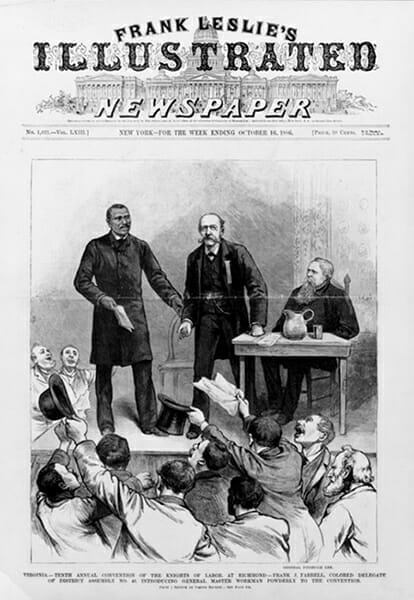

During the last quarter of the nineteenth century, as many as three million Americans joined the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor (KOL). At its peak in 1886, the KOL had between 700,000 and one million members, making it the largest labor organization in U.S. history to that point. In Alabama, KOL membership peaked at some 5,600 in late 1887 and despite a rather turbulent history that saw the organization collapse and resurrect itself several times, the KOL ultimately remained active and significant in Alabama longer than in most other states. Organizing workers regardless of skill, race (with the exception of the Chinese), or gender, the KOL not only provided Alabamians with an outlet for protesting long hours, low wages, and the convict-lease system, but also played a significant role in launching the Populist movement of the 1890s.

Knights of Labor Meeting

During the last quarter of the nineteenth century, as many as three million Americans joined the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor (KOL). At its peak in 1886, the KOL had between 700,000 and one million members, making it the largest labor organization in U.S. history to that point. In Alabama, KOL membership peaked at some 5,600 in late 1887 and despite a rather turbulent history that saw the organization collapse and resurrect itself several times, the KOL ultimately remained active and significant in Alabama longer than in most other states. Organizing workers regardless of skill, race (with the exception of the Chinese), or gender, the KOL not only provided Alabamians with an outlet for protesting long hours, low wages, and the convict-lease system, but also played a significant role in launching the Populist movement of the 1890s.

Formed in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1869, the KOL appointed its first southern organizers nine years later, including Edward S. Marshall of Montgomery and Michael F. Moran of Helena. By the end of 1878, the KOL had chartered six local assemblies in Alabama, including two in Mobile and two in Helena, where most members were coal miners. As of May 1880, the KOL had 19 local assemblies and as many as 700 members in the state. During this period, the organization became particularly active in Jefferson County, where many members (white and black alike) were coal miners and active in the Greenback-Labor Party (GLP).

The Alabama KOL declined, along with the GLP, in the early 1880s but entered a period of significant growth in 1885 that coincided with a comparable time of national growth during labor’s “great upheaval,” a period during the mid-1880s of strikes and related violence. At that time, KOL membership in Alabama included coal miners, dry-goods salesmen, woodworkers, machinists, cotton mill workers, ironworkers, lumbermen, and farmers and farmhands. Women and African Americans joined the ranks of Alabama Knights, but the latter were usually organized into all-black local assemblies.

Between 1885 and 1888, the KOL led a number of strikes in Alabama, mostly among coal miners, who struck against wage cuts, the use of convict labor, and the hiring of migrant Italian miners. The KOL also waged boycotts in response to firings or lockouts of workers who belonged to the organization but managed only limited success in these battles. The organization also formed a number of cooperative Knights-owned enterprises in Alabama during this period, including a real estate company and a cigar works. The success of these ventures led the organization to establish two “cooperative towns,” Powderly and Trevellick, in honor of two of the organization’s national leaders, Terence V. Powderly and Richard Trevellick, respectively. (The first of these communities outlived the KOL and is still a part of Birmingham today.) In addition, the KOL joined with other labor and farmer groups in forming the Alabama Union Labor Party in 1887 and the Labor Party of Alabama one year later. These parties won some local elections—KOL state lecturer E. S. Starr became the mayor of Selma in 1889—and helped pave the way for the Populist Party of the 1890s.

By 1889, however, the KOL began to deteriorate in Alabama and across the nation. Unsuccessful miners’ strikes, competition with trade unions affiliated with the newly formed American Federation of Labor (AFL), and internal strife within KOL ranks all contributed to the organization’s demise in Alabama. The KOL still maintained enough significance in 1892 to help launch the Alabama Populist Party, but by the time large strikes broke out among coal miners and railroad workers in 1894, the KOL had been almost completely eclipsed by other unions.

In 1898, as the nation’s economy finally began to recover from the economic panic of 1893 and Alabama’s mining and lumber industries rebounded, the KOL began a remarkable resurgence in the state. At a time when national membership had fallen to somewhere in the range of 20,000 to 50,000 individuals, the KOL had about 5,000 members in Alabama by 1900. The organization’s successes during this period included an agreement with a lumber mill in Brewton in 1899 that gave workers a 25-percent raise and forced the company to pay workers in cash rather than scrip redeemable only at the company store. But by mid-1901, falling timber prices began eroding the KOL’s bargaining power in that industry, and familiar problems such as internal and racial strife within the organization and quarrels with other unions weakened the KOL throughout the state. After 1902, the KOL began to decline in Alabama once again, although it remained active in the state until at least 1908.

Despite its up-and-down existence and ultimate collapse, the KOL nevertheless left a significant legacy in Alabama. It played a pioneering role in organizing workers, leading strikes and boycotts, lobbying for the eradication of the convict-lease system as early as 1886, and fostering unity between industrial workers and farmers. The Alabama State Federation of Labor, formed in 1900, carried many of the KOL’s battles into the twentieth century, playing an active role in politics, helping to get the convict-lease system abolished in 1928, and occasionally collaborating with the Alabama Farmers’ Union to fight for economic and social justice for working-class Alabamians.

Further Reading

- Brennan, James R. “Sawn Timber and Straw Hats: The Development of the Lumber Industry in Escambia County, Alabama, 1880-1910.” Gulf Coast Historical Review 11 (Spring 1996): 41-67.

- Hild, Matthew. “Dixie Knights Redux: The Knights of Labor in Alabama, 1898-1902.” Gulf South Historical Review 17 (Fall 2001): 36-51.

- ———. Greenbackers, Knights of Labor, and Populists: Farmer-Labor Insurgency in the Late-Nineteenth-Century South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007.

- ———. “Building the Alabama Labor Movement: Nicholas Byrne Stack and the Knights of Labor.” Alabama Review 73 (April 2020): 91-117.

- Letwin, Daniel. The Challenge of Interracial Unionism: Alabama Coal Miners, 1898-1921. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

- McLaurin, Melton A. The Knights of Labor in the South. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1978.