Territorial Period and Early Statehood

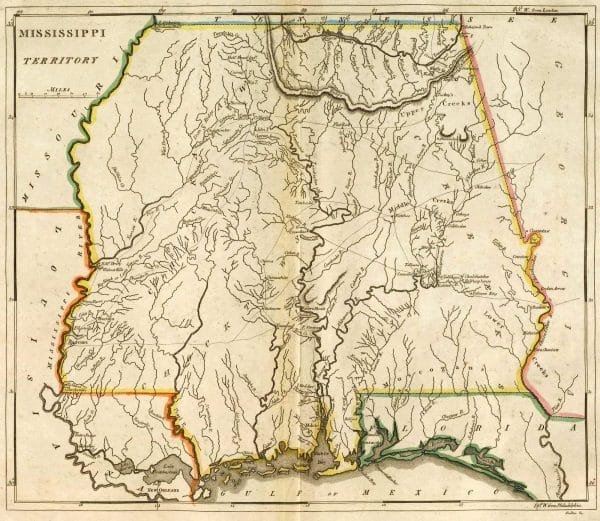

Mississippi Territory

The early history of Alabama as a territory and a state was marked by an increasing number of Americans migrating into the region that, with the United States’ continual expansion westward, became known as the “Old Southwest.” As these migrants, rich and poor, white and black, free and enslaved, travelled southward, they brought with them traditions of government, labor, culture, and social order, all of which would shape life on America’s southern frontier. The period was marked by turbulent relations with Native Americans, the development of a cotton-based economy dependent on enslaved labor, and political conflict between two political factions within state government, one based in the Black Belt region and the other centered in the northern hill country.

Mississippi Territory

The early history of Alabama as a territory and a state was marked by an increasing number of Americans migrating into the region that, with the United States’ continual expansion westward, became known as the “Old Southwest.” As these migrants, rich and poor, white and black, free and enslaved, travelled southward, they brought with them traditions of government, labor, culture, and social order, all of which would shape life on America’s southern frontier. The period was marked by turbulent relations with Native Americans, the development of a cotton-based economy dependent on enslaved labor, and political conflict between two political factions within state government, one based in the Black Belt region and the other centered in the northern hill country.

Territorial Period (1798-1819)

Becoming a Territory

The young United States acquired the British claims to all lands east of the Mississippi River, including present-day Alabama, as part of the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolution. The U.S. Congress, in April 1798, created the Mississippi Territory out of lands north of the 31st parallel formerly claimed by the colony of Georgia. By 1804, the territory possessed two white settlements, St. Stephens on the lower Tombigbee River and Natchez on the lower Mississippi. The territory’s boundaries included: Spanish Florida to the south, the Mississippi River to the west, the state of Tennessee to the north, and to the east, Georgia, which had grudgingly relinquished its claims to the area in 1802. No sooner had the territory been formed than questions over its division arose. Under pressure from white southerners desiring to see two slave states emerge, Congress created the Alabama Territory out of the eastern half of the Mississippi Territory on March 3, 1817. The act named William Wyatt Bibb of Georgia as governor of the territory of Alabama. The population grew so rapidly in the Alabama Territory (from 1,250 residents in 1800 to 9,046 in 1810 to 127,901 by 1820) that by 1817, state representatives at St. Stephens, the seat of the territorial government, were overwhelmed with petitions for statehood.

Native American Inhabitants

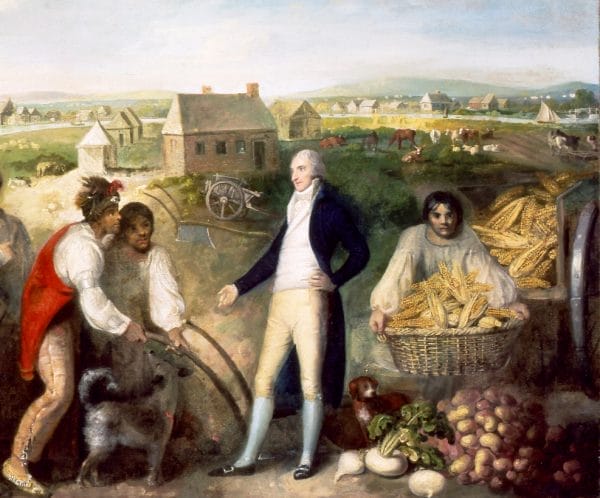

Benjamin Hawkins and the Creek Indians

Alabama’s Native American residents, predominantly members of the Creek, Cherokee, and Choctaw nations, played a central role during the state’s territorial period as conflicts between Indians and white settlers during the early 1800s paved the way for the creation of the state of Alabama. Indian frustrations over white land claims and the resulting Creek War of 1813-14 were rooted in the policies known as the “plan of civilization” initiated during Pres. George Washington’s administration. With orders from the federal government, Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins pressed southeastern Indians to adopt white methods of education, agriculture, and labor systems that relied on enslaved African Americans and urged them to accept white clothing styles, gender roles, and Christianity. White expansionists felt that by accepting these and other characteristics, Native Americans would assimilate into mainstream American culture and abandon their vast hunting lands more quickly to white settlers.

Benjamin Hawkins and the Creek Indians

Alabama’s Native American residents, predominantly members of the Creek, Cherokee, and Choctaw nations, played a central role during the state’s territorial period as conflicts between Indians and white settlers during the early 1800s paved the way for the creation of the state of Alabama. Indian frustrations over white land claims and the resulting Creek War of 1813-14 were rooted in the policies known as the “plan of civilization” initiated during Pres. George Washington’s administration. With orders from the federal government, Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins pressed southeastern Indians to adopt white methods of education, agriculture, and labor systems that relied on enslaved African Americans and urged them to accept white clothing styles, gender roles, and Christianity. White expansionists felt that by accepting these and other characteristics, Native Americans would assimilate into mainstream American culture and abandon their vast hunting lands more quickly to white settlers.

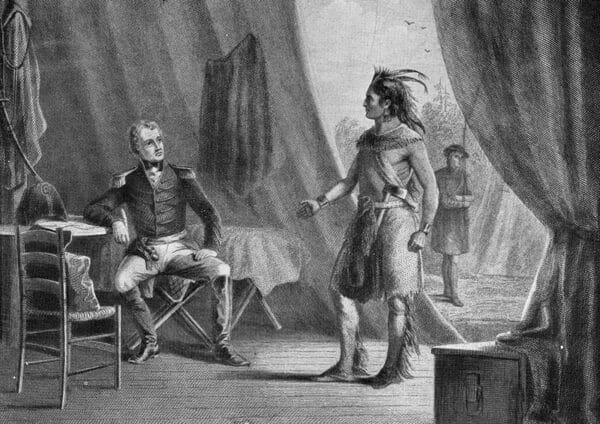

Massacre at Fort Mims

Not all Indian peoples resisted the transformation. One eighteenth-century Creek leader who embraced aspects of both European and Creek culture was Alexander McGillivray, the son of a prominent Creek woman and a Scottish deerskin trader who ultimately became one of Georgia’s leading citizens. Well-read and affluent, McGillivray emerged in the 1780s and 1790s as an influential politician who bridged the divide between early American leaders and Creek peoples by centralizing Creek power and managing the affairs of the Creek Nation. Ultimately, he was recognized by the Washington administration as the most important of the Creek leaders. Yet, the opportunity to expose internal division in Indian societies over “civilization” presented itself as the War of 1812 between Americans and the British seemingly ran parallel with the internal Creek War in the southeastern United States. During the Creek War, the United States sided with the Lower Creeks led by men like McGillivray who had accepted and profited from the new order but who were directly challenged by Upper Creeks engaged in a religious revival movement centered on defending “traditional” Indian life. The pan-Indian leader Tecumseh and his followers, known as Red Sticks, led this movement to reject white culture. Andrew Jackson’s defeat of the Creek insurgency at Tohopeka, or Horseshoe Bend, in March 1814 won him national fame for subduing Indian opposition to white expansion. This and other engagements like those at or Burnt Corn Creek and Fort Mims demonstrated the complexity of the evolving relationships between white Americans, Indian residents, and their mixed-ancestry children on the Alabama frontier. Jackson’s own presidency ensured that the Creek War was not the last time the Indian inhabitants of Alabama would be forced to deal with the federal government’s support of white expansion.

Massacre at Fort Mims

Not all Indian peoples resisted the transformation. One eighteenth-century Creek leader who embraced aspects of both European and Creek culture was Alexander McGillivray, the son of a prominent Creek woman and a Scottish deerskin trader who ultimately became one of Georgia’s leading citizens. Well-read and affluent, McGillivray emerged in the 1780s and 1790s as an influential politician who bridged the divide between early American leaders and Creek peoples by centralizing Creek power and managing the affairs of the Creek Nation. Ultimately, he was recognized by the Washington administration as the most important of the Creek leaders. Yet, the opportunity to expose internal division in Indian societies over “civilization” presented itself as the War of 1812 between Americans and the British seemingly ran parallel with the internal Creek War in the southeastern United States. During the Creek War, the United States sided with the Lower Creeks led by men like McGillivray who had accepted and profited from the new order but who were directly challenged by Upper Creeks engaged in a religious revival movement centered on defending “traditional” Indian life. The pan-Indian leader Tecumseh and his followers, known as Red Sticks, led this movement to reject white culture. Andrew Jackson’s defeat of the Creek insurgency at Tohopeka, or Horseshoe Bend, in March 1814 won him national fame for subduing Indian opposition to white expansion. This and other engagements like those at or Burnt Corn Creek and Fort Mims demonstrated the complexity of the evolving relationships between white Americans, Indian residents, and their mixed-ancestry children on the Alabama frontier. Jackson’s own presidency ensured that the Creek War was not the last time the Indian inhabitants of Alabama would be forced to deal with the federal government’s support of white expansion.

Land Conflicts

The decline of Indian populations spawned by two centuries’ worth of European-introduced diseases, warfare, and eventually formalized land cessions like those included in the 1814 Treaty of Fort Jackson greatly encouraged white relocation to present-day Alabama. The total number of white residents increased dramatically to 309,527 by 1830. As the most intense conflicts with the region’s Native Americans drew to a close by the late 1810s, the struggle for who would control the state’s government, who would be represented, and whose interests would be paramount took center stage.

Treaty of Fort Jackson

Whereas some historians have considered the land-hungry migrants from neighboring southern states such as Georgia, Tennessee, Virginia, and the Carolinas as “settlers,” other historians view the settlement of Alabama differently. They perceive the migration phenomenon commonly referred to as “catching Alabama fever” as a second wave of in-migration that built upon roughly two centuries of European encroachment. Fueling this influx during the early 1800s was the idea commonly held among white migrants that this new territory represented a frontier filled with opportunity. In the Old Southwest, the possibility of a new beginning enticed migrants whose opportunities for land ownership had narrowed in older southern states. In addition to the poorer whites looking for cheap land came the sons of Virginia and South Carolina planters as well as those who had settled briefly in Georgia, such as members of the Broad River Group. These men carried with them the capital to establish themselves as the frontier’s social and political elites. Emerging conflicts between these two classes of new migrants manifested themselves in land sales and the creation of the state’s first constitution.

Treaty of Fort Jackson

Whereas some historians have considered the land-hungry migrants from neighboring southern states such as Georgia, Tennessee, Virginia, and the Carolinas as “settlers,” other historians view the settlement of Alabama differently. They perceive the migration phenomenon commonly referred to as “catching Alabama fever” as a second wave of in-migration that built upon roughly two centuries of European encroachment. Fueling this influx during the early 1800s was the idea commonly held among white migrants that this new territory represented a frontier filled with opportunity. In the Old Southwest, the possibility of a new beginning enticed migrants whose opportunities for land ownership had narrowed in older southern states. In addition to the poorer whites looking for cheap land came the sons of Virginia and South Carolina planters as well as those who had settled briefly in Georgia, such as members of the Broad River Group. These men carried with them the capital to establish themselves as the frontier’s social and political elites. Emerging conflicts between these two classes of new migrants manifested themselves in land sales and the creation of the state’s first constitution.

Early Statehood (1819-1828)

Politics and Society

Men from various social classes, including experienced statesmen like John W. Walker as well as frontiersmen like Samuel Dale, gathered in July 1819 at a constitutional convention held in the temporary capital city of Huntsville (which featured a surprise visit by Pres. James Monroe). In the subsequent constitution, delegates combined elements of self-interest and republican idealism in measures that included legalizing slavery and designating public lands for educational institutions. The document rejected the restrictive nature of other emerging southern legal systems, such as those of Mississippi and Louisiana, where limitations on suffrage and imprisonment for debts were quite common. Under this new constitution, Alabama was granted statehood on December 14, 1819 and William Wyatt Bibb was elected the state’s first governor.

William Wyatt Bibb, 1819

In frontier Alabama, and throughout its formative period, political ideologies clashed and co-mingled as politicians attempted to form a state government that all members of the body politic could support. Alabama’s early governors and party stalwarts embraced these ideological debates as interest-group politics emerged. The majority of elite Alabamians concentrated in the Black Belt and in Huntsville supported the “Georgia faction,” led by the state’s first governor, William Wyatt Bibb (1819-20), and his brother and successor Governor Thomas Bibb (1820-21); individuals from the middling and lower classes sided with governors Israel Pickens (1821-25) and John Murphy (1825-29) as they championed the interests of the “common man” versus those of the landed and monied elite.

William Wyatt Bibb, 1819

In frontier Alabama, and throughout its formative period, political ideologies clashed and co-mingled as politicians attempted to form a state government that all members of the body politic could support. Alabama’s early governors and party stalwarts embraced these ideological debates as interest-group politics emerged. The majority of elite Alabamians concentrated in the Black Belt and in Huntsville supported the “Georgia faction,” led by the state’s first governor, William Wyatt Bibb (1819-20), and his brother and successor Governor Thomas Bibb (1820-21); individuals from the middling and lower classes sided with governors Israel Pickens (1821-25) and John Murphy (1825-29) as they championed the interests of the “common man” versus those of the landed and monied elite.

State Capitol at Cahaba

Early Alabama possessed an active journalistic culture that offered a venue for many of these early political debates to take place. Various newspapers like the Cahawba Press and Alabama Intelligencer and Huntsville’s Alabama Republican and Huntsville Democrat demonstrated the regional splits that expanded during Alabama’s early decades. This conflict for consensus seems to be most clearly expressed during the negotiations for the permanent seat of the state’s capital. Nevertheless, early Alabamians could act collectively when the opportunity to fashion themselves as frontier yet civilized and cultured Americans presented itself. In April 1825, French nobleman and Revolutionary war hero the Marquis de la Lafayette journeyed through Alabama and attended lavish balls held in his honor at Montgomery, Cahawba and Mobile, costing the fledgling state an estimated $17,000. Alabamians long delighted in retelling how they entertained the hero the American and French Revolutions even as the experience left the young state facing an exorbitant debt.

State Capitol at Cahaba

Early Alabama possessed an active journalistic culture that offered a venue for many of these early political debates to take place. Various newspapers like the Cahawba Press and Alabama Intelligencer and Huntsville’s Alabama Republican and Huntsville Democrat demonstrated the regional splits that expanded during Alabama’s early decades. This conflict for consensus seems to be most clearly expressed during the negotiations for the permanent seat of the state’s capital. Nevertheless, early Alabamians could act collectively when the opportunity to fashion themselves as frontier yet civilized and cultured Americans presented itself. In April 1825, French nobleman and Revolutionary war hero the Marquis de la Lafayette journeyed through Alabama and attended lavish balls held in his honor at Montgomery, Cahawba and Mobile, costing the fledgling state an estimated $17,000. Alabamians long delighted in retelling how they entertained the hero the American and French Revolutions even as the experience left the young state facing an exorbitant debt.

Agriculture, Economics, and Slavery

Slavery emerged as the dominant labor system in Alabama, driven by the state’s rapidly developing cotton economy, and it had a significant impact on Alabamians in the Tennessee River Valley and those of the Tombigbee and Alabama River Valleys alike. By 1820, Alabama’s population had swelled to more than 125,000 persons, with slaves making up 31 percent of the total, or nearly 40,000 individuals. State politics in the 1820s centered on debates about the proposed creation of a state bank engineered by Gov. Israel Pickens. The banking institutions within the state were directly linked to the plight of fledgling planters and frontier yeomen who seemingly divided in the 1830s as the Black-Belt region grew in economic and political importance. Some distinction was no doubt drawn between the earliest white settlers, who possessed enough capital to acquire large tracts of land, and those who did not at the 1817 land auctions at Milledgeville, Georgia, and the much larger sale at Huntsville in 1818. In early Alabama, the primary necessity for agricultural producers, be they small farmers growing corn or large plantation owners manufacturing cotton, was land. Thus, the desire for land and the funding it necessitated from banking institutions had the potential to unite various socio-economic classes; yet it could also divide them, as elites were often able to acquire the best farm lands and the most slaves because they controlled the state’s networks of private banks.

Vine and Olive Colony

Although settlers of the upper and lower river valleys were involved in some form of agriculture, the centrality of slave labor evolved differently in the two regions. Farmers small and large in these districts had early on experimented with growing indigo, olives, small grains like wheat, and grapes (such as the French settlers of the Vine and Olive Colony), but they soon directed their attention to the emerging cotton culture. The degrees to which Alabamians did so exacerbated regional differences by the close of the 1820s. At the beginning of the 1830s, planters who staked out lands in lower Alabama began raising cotton with the assistance of slave labor, while in the hilly upcountry the majority of the inhabitants’ interests centered on small-scale subsistence agriculture. These regional divisions and their continued evolution would go on to affect state politics and daily life for all Alabamians throughout the early nineteenth century.

Vine and Olive Colony

Although settlers of the upper and lower river valleys were involved in some form of agriculture, the centrality of slave labor evolved differently in the two regions. Farmers small and large in these districts had early on experimented with growing indigo, olives, small grains like wheat, and grapes (such as the French settlers of the Vine and Olive Colony), but they soon directed their attention to the emerging cotton culture. The degrees to which Alabamians did so exacerbated regional differences by the close of the 1820s. At the beginning of the 1830s, planters who staked out lands in lower Alabama began raising cotton with the assistance of slave labor, while in the hilly upcountry the majority of the inhabitants’ interests centered on small-scale subsistence agriculture. These regional divisions and their continued evolution would go on to affect state politics and daily life for all Alabamians throughout the early nineteenth century.

Further Reading

- Abernethy, Thomas Perkins. The Formative Period in Alabama, 1815-1828. 1965. Reprint, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1990.

- Beidler, Philip D. First Books: The Printed Word and Cultural Formation in Early Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999.

- Blaufarb, Rafe. Bonapartists in the Borderlands: French Exiles and Refugees on the Gulf Coast, 1815-1835. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005.

- Brantley, William H. Three Capitals: A Book About the First Three Capitals of Alabama: St. Stephens, Huntsville, & Cahawba. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1976.

- Dupre, Daniel. Transforming the Cotton Frontier: Madison County, Alabama, 1800-1840. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997.

- Griffith, Benjamin W., Jr. McIntosh and Weatherford: Creek Indian Leaders. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1998.

- Saunt, Claudio. A New Order of Things: Property, Power, and the Transformation of the Creek Indians, 1733-1816. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Southerland, Henry DeLeon, Jr., and Jerry Elijah Brown. The Federal Road through Georgia, and Creek Nation, and Alabama, 1806-1836. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1989.

- Thornton, J. Mills. Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800-1860. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978.