Treaty of New York (1790)

The 1790 Treaty of New York, between George Washington’s fledgling constitutional government and representatives of the Creek and Seminole Nations, stands out among several early agreements between the United States and Native American sovereignties. It is most notable in American diplomacy for its inclusion of agreements known only to certain parties. The treaty effectively ended the Spanish monopoly of trade with the Creeks and limited British influence on the southwestern frontier. Additionally, the document asserted U.S. authority to treat with the Creek Nation, ending efforts by the state of Georgia to act unilaterally and separately with the various tribes within and adjacent to its territory.

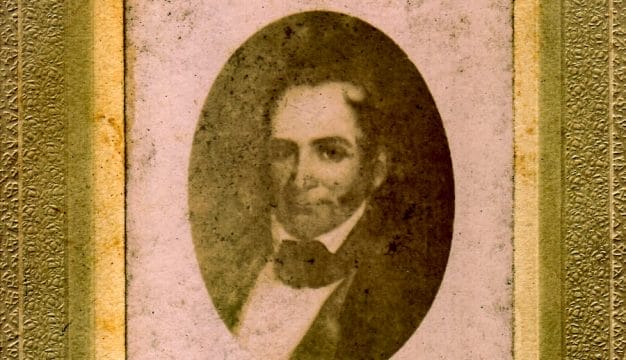

The treaty was crafted by Secretary of War Henry Knox, representing the U.S. government, and Alexander McGillivray, representing a select group of Creek chiefs who had accompanied him to New York. McGillivray also claimed to speak for the Seminoles. Much of the text was likely proposed by McGillivray, setting a precedent in which prominent individuals were given precedence over tribal councils in future negotiations between the U.S. government and Native American nations. The treating parties pledged lasting peace and friendship. Creeks and Seminoles within the boundaries of the United States would be subject to federal laws, rather than Georgia state laws. Creeks and Seminoles in Florida remained subject to Spanish law, although they too came under U.S. control in 1795, with the ratification of Pinckney’s Treaty. British right to passage through Creek lands was also restricted, and Creek prisoners were to be returned from American custody. The Creeks also ceded the land belonging to the allied Oconee Indians, which had been a contentious issue, and survey procedures were specified. For their part, the Creeks were granted an annual payment. In addition, Creeks within American territory and Americans in Creek (and American) territory would be subject to U.S. law, but Americans settling in Creek territory would forfeit federal protection. In an effort to encourage Creeks and Seminoles to take up agriculture, the U.S. government offered to provide domestic animals, agricultural tools, and up to four interpreters, intended to act as farm advisors, as part of its “plan of civilization”

As mentioned above, the treaty also contained six articles, set forth in a separate document, that were kept secret from the majority of the Creek leaders. The first laid out the structure of future commerce between the United States and the Creek Nation, including shifting the traffic in trade goods through American ports and away from Spanish territory and ports of entry. The United States also agreed to pay select Creek chiefs a $100 yearly stipend and to commission Alexander McGillivray as a brigadier general with annual pay of $1,200. This last gesture was aimed at encouraging McGillivray to promote U.S. interests and policies among his fellow Creeks.

The fifth secret article was likely the most significant. It stated, “The United States agree to educate and clothe such of the Creek youth as shall be agreed upon, not exceeding four in number at any one time.” Educated Native Americans would, and did, readily adopt and help promote mainstream American culture. Many became planters and, like McGillivray, merchants. David Tate, McGillivray’s nephew and British Indian agent David Taitt‘s son, was the first Creek student selected for federally subsidized education, and he was soon followed by other of McGillivray’s kinsmen. Tate’s nephew and McGillivray’s grand-nephew, David Moniac, was the last to benefit and became Alabama‘s first West Point cadet and graduate in 1822.

Initially, the secret articles drew acrimonious and sometimes public debate, with the most strenuous objections directed at inclusions regarding the application of federal law in Creek territory and the special treatment granted to McGillivray. Drafters publicly agreed to delete the secret articles, although in fact some were quietly implemented during the succeeding two decades. The secret articles were not made public until 1848, when historian Albert James Pickett discovered the Creeks’ original text of the secret articles and paraphrased them, sometimes ambiguously, in his History of Alabama and Incidentally of Georgia and Mississippi from the Earliest Period.

The Treaty of New York of 1790, crafted probably in large measure by Alexander McGillivray, one of the most interesting figures in the history of the Southeast, was ultimately valuable to the state’s creation. It confirmed the federal government’s exclusive authority under the U.S. Constitution for all foreign relations, including treating with sovereign Indian nations, and thus made the disposition of Creek and other Native American lands inside the state of Georgia a federal issue. This move in turn led to the establishment of the territories and later states of Mississippi and Alabama.

Further Reading

- Appleton, J. L., and R. D. Ward. “Albert James Pickett and the Case of the Secret Articles: Historians and the Treaty of New York of 1790.” Alabama Review 51 (January 1998): 3-36.

- Kappler, C. J., ed. Indian Affairs, Laws and Treaties 2. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1904.

- Wright, J. L., Jr. “Creek-American Treaty of 1790: Alexander McGillivray and the Diplomacy of the Old Southwest.” Georgia Historical Quarterly 51 (December 1967): 381-400.