Thomas E. Kilby (1919-23)

Perhaps remembered most for having his name placed on an Alabama prison, Thomas Kilby (1865-1943) was one of the state’s more progressive governors. He oversaw improvements in state services, including education, mental health, and veterans’ benefits. He also improved the state’s finances and established the Child Welfare Department. In addition to his political activities, Kilby was a leading industrial and business force in the state, establishing several important companies in his home town of Anniston.

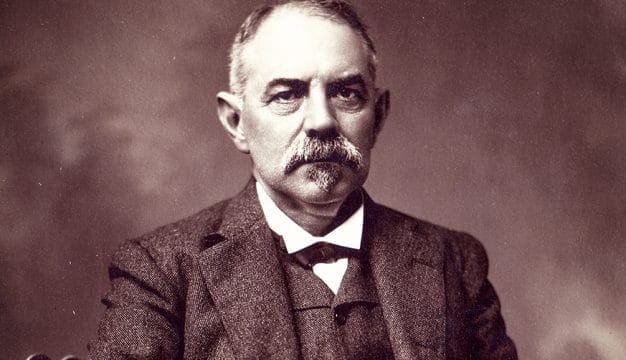

Thomas E. Kilby

Thomas Erby Kilby was born on July 9, 1865, in Lebanon, Tennessee, to Peyton Phillips Kilby and Sarah Ann Marchant Kilby. His family moved to Atlanta, Georgia, where Kilby received his early and only education in the city’s public grammar schools. He began his business career in 1887 as an agent for the Georgia-Pacific Railroad in Anniston, Alabama. In 1889, he entered the steel business with Horry Clark, who owned Clark and Company, and soon he was made a partner in the renamed Clark and Kelly Company. Over the next decade, the company evolved into a major operation renamed the Kilby Steel Company. The future governor also founded the Alabama Frog and Switch Company, and he served as president of both it and the Kilby Steel Company. Kilby married Mary Elizabeth Clark on June 5, 1894, and the couple would have three children.

Thomas E. Kilby

Thomas Erby Kilby was born on July 9, 1865, in Lebanon, Tennessee, to Peyton Phillips Kilby and Sarah Ann Marchant Kilby. His family moved to Atlanta, Georgia, where Kilby received his early and only education in the city’s public grammar schools. He began his business career in 1887 as an agent for the Georgia-Pacific Railroad in Anniston, Alabama. In 1889, he entered the steel business with Horry Clark, who owned Clark and Company, and soon he was made a partner in the renamed Clark and Kelly Company. Over the next decade, the company evolved into a major operation renamed the Kilby Steel Company. The future governor also founded the Alabama Frog and Switch Company, and he served as president of both it and the Kilby Steel Company. Kilby married Mary Elizabeth Clark on June 5, 1894, and the couple would have three children.

In 1911, Kilby foresaw the potential profits to be made in cast-iron pipe and organized the Alabama Pipe and Foundry Company. By 1921, he had purchased some dozen independent plants, creating a large and profitable business that he controlled until his death in 1943. Kilby extended his industrial business success into banking in the early twentieth century, when he became president of the City National Bank of Anniston, a position he held until he became governor and to which he returned as chairman after his governorship.

Kilby was elected to the Anniston City Council in 1898 and was influential in saving the city from bankruptcy by convincing those who held city debt to accept payment at a lower rate of interest. The meagerly educated Kilby also served on the city’s school board, where he acquired a lifelong commitment to education. In 1905, he ran unopposed for mayor of Anniston and served two successive terms, during which he maintained conservative fiscal, pro-business, and pro-development policies. Despite fiscal restraint, Kilby demonstrated strong progressive tendencies and increased the monies spent on prisoners for meals and medical treatment, approved construction of sanitary sewers, appointed a milk inspector, enforced gambling laws, and provided greater oversight of local water rates.

At the conclusion of his second term as mayor, Kilby travelled to Europe to study state and municipal governments there. After returning to Alabama, he won election as a Democrat in 1910 to the state Senate representing Calhoun County. In the legislature, he was a strong proponent of statewide Prohibition and helped to write a new revenue bill. In 1915, he was elected lieutenant governor, and his term was marked by the restoration of appointive powers for legislative committee assignments from the governor back to the lieutenant governor. Having won that power, Kilby saw that every legislative committee had a majority of Prohibition supporters, insuring the passage, over Gov. Charles Henderson‘s veto, of a statewide Prohibition law. Kilby’s disgust with the legislature for delaying enactment of revenue bills until the last moment propelled him to run for governor in 1918.

Kilby’s campaign aimed to reform the way the legislature enacted budgets and raised revenue for the state’s business. He refused all campaign donations, and the contest was a quiet one, in part, because the United States was still in the midst of World War I. Kilby’s platform proposed an executive budget system that included an audit of state finances, increased support for public education, revision of state tax laws, increased pay for jury duty, abolition of the convict-lease system, and support for the Eighteenth Amendment to create national Prohibition.

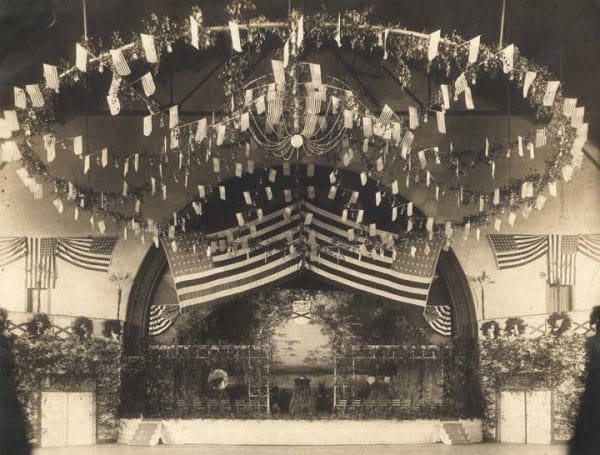

Kilby defeated William W. Brandon and was inaugurated in January 1919. The war in Europe had ended, soldiers were returning home, and the inauguration was lively and filled with more excitement than usual. Kilby made a brief speech in which he advocated increased support for education and public health, more attention to law enforcement, and good roads. Then, in a new event for gubernatorial inaugurals, he received the public for about two hours in the Capitol.

Thomas Kilby Inauguration

Kilby benefited from a brief period of postwar prosperity in 1919, but he also inherited a large bonded indebtedness and had to deal with postwar inflation and increased cost of services. Kilby proposed a balanced budget to the legislature, endorsed a graduated income tax, and recommended an excess profits tax on businesses to bring in needed revenue. He proposed a tax on the products of mines and timber land, asserting that the natural resources of the state were being depleted and that such taxes would repay the state for its loss. In addition, Kilby promoted administrative reforms. He recommended abolishment of county boards of equalization in favor of a person in each county appointed by the governor to equalize taxes. He created a Board of Control and Economy to purchase supplies for all departments of the state, manage the charitable and educational institutions of the state, and oversee the Convict Department. A budget commission was created, with the governor, attorney general, and state auditor comprising its membership. When the income tax bill was declared unconstitutional by the Alabama Supreme Court, Kilby attempted to raise ad valorem taxes. The governor managed to pay off more than $1 million in floating indebtedness, retire more than $500,000 in bonds, and pay off more than $1.5 million in unpaid warrants inherited from previous administrations. Nevertheless, he, too, left a debt for his successor.

Thomas Kilby Inauguration

Kilby benefited from a brief period of postwar prosperity in 1919, but he also inherited a large bonded indebtedness and had to deal with postwar inflation and increased cost of services. Kilby proposed a balanced budget to the legislature, endorsed a graduated income tax, and recommended an excess profits tax on businesses to bring in needed revenue. He proposed a tax on the products of mines and timber land, asserting that the natural resources of the state were being depleted and that such taxes would repay the state for its loss. In addition, Kilby promoted administrative reforms. He recommended abolishment of county boards of equalization in favor of a person in each county appointed by the governor to equalize taxes. He created a Board of Control and Economy to purchase supplies for all departments of the state, manage the charitable and educational institutions of the state, and oversee the Convict Department. A budget commission was created, with the governor, attorney general, and state auditor comprising its membership. When the income tax bill was declared unconstitutional by the Alabama Supreme Court, Kilby attempted to raise ad valorem taxes. The governor managed to pay off more than $1 million in floating indebtedness, retire more than $500,000 in bonds, and pay off more than $1.5 million in unpaid warrants inherited from previous administrations. Nevertheless, he, too, left a debt for his successor.

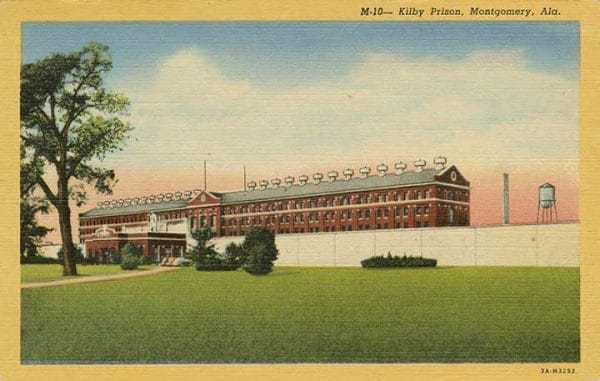

Kilby Prison

Kilby justified his tax increase proposals by linking them to humanitarian benefits. He had run for governor on a program of social reform. He advocated Prohibition, a “reform” he believed would destroy saloons, lessen the crime and prostitution that occurred around them, and benefit family life and the workplace as well. Kilby campaigned on keeping Alabama “bone dry” and advocated ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919. He also wanted to end convict leasing, but his efforts were unsuccessful, and the system was not eliminated until late in 1927, making Alabama the last state in the nation to abandon it. Nonetheless, Kilby’s activism brought better sanitation and sleeping arrangements at the convict camps, and the state constructed a new prison facility, bearing the governor’s name, that included a dairy, hog farms, and a spinning mill in which prisoners worked.

Kilby Prison

Kilby justified his tax increase proposals by linking them to humanitarian benefits. He had run for governor on a program of social reform. He advocated Prohibition, a “reform” he believed would destroy saloons, lessen the crime and prostitution that occurred around them, and benefit family life and the workplace as well. Kilby campaigned on keeping Alabama “bone dry” and advocated ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919. He also wanted to end convict leasing, but his efforts were unsuccessful, and the system was not eliminated until late in 1927, making Alabama the last state in the nation to abandon it. Nonetheless, Kilby’s activism brought better sanitation and sleeping arrangements at the convict camps, and the state constructed a new prison facility, bearing the governor’s name, that included a dairy, hog farms, and a spinning mill in which prisoners worked.

Kilby was involved with other social issues as well. He expanded services to the mentally ill and increased funding to Bryce Hospital. One of his most lasting accomplishments was the creation of the Child Welfare Department in 1919, which began enforcing laws that regulated the employment of children. He also secured a $50,000 appropriation from the legislature to support construction of the Alabama World War Memorial Building, which was to house the Alabama Department of Archives and History and the State Department of Education. During his tenure, the budget for farm demonstration agents was quadrupled. He increased appropriations to the Public Health Department, and workers’ compensation in the state became law in July 1919. Confederate veterans received an increase in their pensions, and he also led the movement to sell $25 million in state bonds in order to earn matching funds under the Good Roads Act sponsored by Alabama senator John Hollis Bankhead Sr.

Ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was a controversial issue in the 1919 legislative session. On this issue Kilby took no stand, although after the vote he expressed regret that the woman suffrage ratification was defeated in the state. In 1920, after national ratification was completed and women won the vote, Kilby called a special session of the legislature to provide for the registration of women to vote in Alabama.

Kilby displayed even greater passion for improving education in the state. He obtained additional funds for the Boys Industrial School and for the State Training School for Girls. Under his prodding, the legislature authorized a commission of experts, led by U.S. Commissioner of Education Philander P. Claxton, to make recommendations for the Alabama school system. They suggested more streamlined administration and increased funding, and the legislature concurred. A new school code was enacted in 1919, vesting more power in the state board of education. Vocational education received new emphasis as well, and spending for education increased more than 100 percent, rising from $3,750,000 in 1919 to $8,269,596 in 1922.

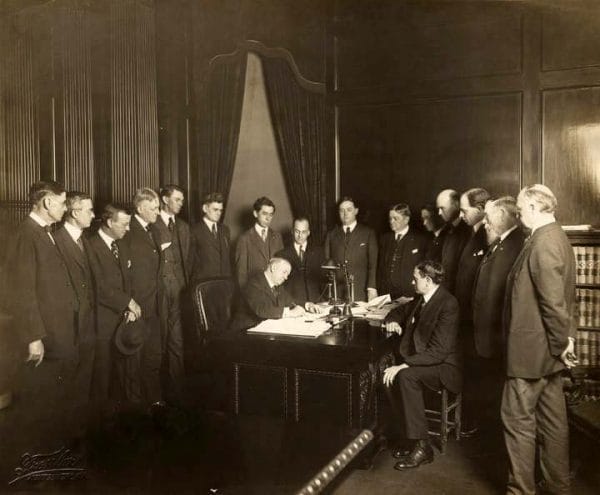

Thomas Kilby Bill Signing

Kilby’s attitude toward upholding the law was exemplified in two disparate ways. In 1919, he used the power of his office to ensure that the perpetrators of a lynching in Baldwin County were arrested and convicted. Likewise, he used his executive powers to protect nonstriking miners during a 1919 strike in the Birmingham coal fields. The essential issue in this case was whether mine owners would be forced to recognize the union. When shortages of coal began to occur, Kilby sent in units of the state’s National Guard to end the strike, and non-union laborers replaced the strikers, effectively, if only temporarily, negating the United Mine Workers efforts in Alabama. Social and economic equity held little appeal for Kilby, especially because many of the striking miners were black. His numerous efforts at social progress were thus overshadowed by his actions during this and other strikes. Kilby’s progressivism was that of the businessman. He set the state’s finances on a businesslike footing, enforced accountability, and streamlined government while increasing services and benefits to citizens considered deserving. He understood that government action could be the engine of economic expansion and that education was essential to economic and social success. In 1921, Kilby earned the distinction of being the first living person featured on a coin issued by the U.S. Mint. The commemorative coin was issued in honor of Alabama’s 1919 centennial of admission to the Union.

Thomas Kilby Bill Signing

Kilby’s attitude toward upholding the law was exemplified in two disparate ways. In 1919, he used the power of his office to ensure that the perpetrators of a lynching in Baldwin County were arrested and convicted. Likewise, he used his executive powers to protect nonstriking miners during a 1919 strike in the Birmingham coal fields. The essential issue in this case was whether mine owners would be forced to recognize the union. When shortages of coal began to occur, Kilby sent in units of the state’s National Guard to end the strike, and non-union laborers replaced the strikers, effectively, if only temporarily, negating the United Mine Workers efforts in Alabama. Social and economic equity held little appeal for Kilby, especially because many of the striking miners were black. His numerous efforts at social progress were thus overshadowed by his actions during this and other strikes. Kilby’s progressivism was that of the businessman. He set the state’s finances on a businesslike footing, enforced accountability, and streamlined government while increasing services and benefits to citizens considered deserving. He understood that government action could be the engine of economic expansion and that education was essential to economic and social success. In 1921, Kilby earned the distinction of being the first living person featured on a coin issued by the U.S. Mint. The commemorative coin was issued in honor of Alabama’s 1919 centennial of admission to the Union.

In perhaps his most progressive moment, Kilby urged a new constitution for Alabama. In January 1923, as he was leaving office, he opined to the legislature that progressive legislation had been restricted or eliminated because of constitutional Prohibition. He went on to say that a constitutional commission of about 35 citizens needed to be created from various professions, such as farmers, businessmen, educators, bankers, doctors, lawyers, the press, and organized labor. Those citizens could thoroughly study and review the constitution and bring it up to date.

Kilby won no other political offices after his term as governor. He ran for the U.S. Senate in 1926 and in 1932 but lost to Hugo Black both times. In the first race, Kilby treated Black condescendingly and concentrated on debating and defeating his other opponent, John Bankhead Jr. As they hurled insults at one another, Black moved up in the polls. Kilby finished last in a field of five candidates in 1926 and fared little better against the incumbent Black in 1932. He returned to his business pursuits in Anniston and died there on October 22, 1943, and was buried in Highland Cemetery there.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Kilby, Thomas Erby. Administrative files, 1919–1923. Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery.

- Owen, Emily. Thomas E. Kilby in Local and State Government. Anniston, Ala.: Birmingham Publishing, 1948.

- Stewart, William H. “Failure of Reform: Attempts to Rewrite the 1901 Constitution.” In A Century of Controversy: Constitutional Reform in Alabama. Bailey Thomson, ed. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.

- Straw, Richard A. “The United Mine Workers of America and the 1920 Coal Strike in Alabama.” Alabama Review 28 (April 1975): 104–27.