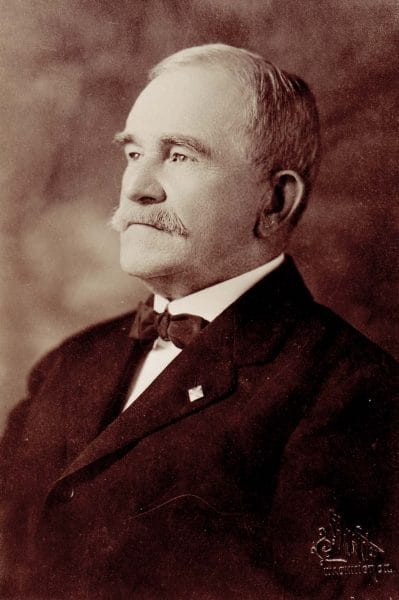

Joseph F. Johnston (1896-1900)

Joseph F. Johnston (1843-1913) served two terms as governor, from 1896 to 1900, and was in office during the four years surrounding the crisis leading up to the passage of the Constitution of 1901, which were among the most tumultuous in Alabama‘s history. After leaving office, Johnston was a candidate for the U.S. Senate against incumbent John Tyler Morgan, and for governor again in 1902, when the state held its first primary election. Both of these campaigns were highly contentious, as Johnston continued his fight against Democratic Party leaders that began in his second term.

Joseph F. Johnston

Joseph Forney Johnston was born on March 23, 1843, in Lincoln County, North Carolina, and grew up on the family farm. In 1860, he moved with his parents to Alabama and attended school in Talladega. At age 18, he volunteered for the Confederate Army and rose from private to captain and was wounded four times. After the war, he practiced law in Selma, Dallas County, until 1884, when he moved to the new boomtown of Birmingham to become a banker. Johnston served as president of the Alabama National Bank for three years, and then became president of the Sloss Iron and Steel Company, the largest manufacturing firm in the city. Johnston’s achievements in business were matched by his accomplishments in politics. Active in the Democratic Party in Selma during Reconstruction, he used his connections with leading figures in banking and steel to become a major figure in the party at the state level after his move to Birmingham. His links with the Black Belt planters and the Birmingham financial and industrial elite, referred to as the Big Mules, enabled him to align himself with both of the twin pillars of the state’s Democratic Party.

Joseph F. Johnston

Joseph Forney Johnston was born on March 23, 1843, in Lincoln County, North Carolina, and grew up on the family farm. In 1860, he moved with his parents to Alabama and attended school in Talladega. At age 18, he volunteered for the Confederate Army and rose from private to captain and was wounded four times. After the war, he practiced law in Selma, Dallas County, until 1884, when he moved to the new boomtown of Birmingham to become a banker. Johnston served as president of the Alabama National Bank for three years, and then became president of the Sloss Iron and Steel Company, the largest manufacturing firm in the city. Johnston’s achievements in business were matched by his accomplishments in politics. Active in the Democratic Party in Selma during Reconstruction, he used his connections with leading figures in banking and steel to become a major figure in the party at the state level after his move to Birmingham. His links with the Black Belt planters and the Birmingham financial and industrial elite, referred to as the Big Mules, enabled him to align himself with both of the twin pillars of the state’s Democratic Party.

During the early 1890s, Alabama, as well as most southern states, experienced considerable social and political unrest as farmers suffered from severe economic difficulties and desperately needed aid and relief. When the Democratic-controlled state governments failed to respond to their demands, the farmers organized politically to put pressure on, and even defeat, the Democrats. As a leading Democrat who was by now a serious contender for high office, Johnston became deeply involved in his party’s schemes and maneuvers to defeat the farmers and their newly formed party, the Jeffersonian Democrats. (In most of the South, and also in the wheat-growing far-western states of the North, however, they had organized as the People’s Party and were known as Populists).

After his party repelled this challenge on two occasions in 1892 and 1894, primarily by resorting to fraud and tampering with the ballots on Election Day, Johnston realized that the Democrats could not continue to ignore the needs of the state’s farm population and stay in power by fraudulent means. So, in 1896, he ran for governor as a reformer who hoped to moderate the party’s conservatism and clean up its corrupt electoral practices to regain the support of the frustrated and suffering farmers.

Joseph F. Johnston

Johnston won the election, defeating Congressman Richard Henry Clarke, and, once in office, introduced a series of reform measures. Some were intended to encourage economic development, but most aimed at regulating business, such as his proposal for the state railroad commission to set and enforce freight rates, and at forcing under-taxed corporations and large landowners to pay their fair share. The new governor also proposed an investigation into the state’s notorious convict-lease system, road construction, and increased state spending for public schools. Manufacturers, railroad companies, and the conservative wing of the party resisted Johnston’s reforms, however. As a result, his proposals, although limited in scope, often failed to pass, or were passed only in a weakened form.

Joseph F. Johnston

Johnston won the election, defeating Congressman Richard Henry Clarke, and, once in office, introduced a series of reform measures. Some were intended to encourage economic development, but most aimed at regulating business, such as his proposal for the state railroad commission to set and enforce freight rates, and at forcing under-taxed corporations and large landowners to pay their fair share. The new governor also proposed an investigation into the state’s notorious convict-lease system, road construction, and increased state spending for public schools. Manufacturers, railroad companies, and the conservative wing of the party resisted Johnston’s reforms, however. As a result, his proposals, although limited in scope, often failed to pass, or were passed only in a weakened form.

Johnston’s opposition was to become even more vigorous when he proposed a convention to rewrite the state’s constitution. The ensuing struggle preoccupied the state and the embattled governor for four years. In Johnston’s view, Alabama’s 1875 Constitution was harmful because it prevented the state from providing financial aid to emerging industries, whereas its taxing limitations frustrated the efforts of growing cities like Birmingham to fund development and expansion. The most important reason for calling a convention, however, was to restrict suffrage. Disfranchisement would not only eliminate black voters, whom Johnston and most white Alabamians considered unfit to participate in elections; it would also restrict the vote to those of the powerful social classes. Johnston’s initiative was opposed by his conservative, pro-business rivals as well as by many of his new supporters. Farming interests in the up-country, who had earlier been Jeffersonians or Populists, now feared that their poor and illiterate followers would be disfranchised.

After conceding some limitations on what the convention could do, the legislature passed a bill in the 1896-97 session calling for a constitutional convention. In the elections for delegates at large, however, the conservative Democrats won handily and then, anticipating a win of a majority of delegates and thus control of the convention, they insisted that calling the convention be a test of party loyalty. Johnston reacted dramatically by calling a special session of the legislature to repeal the convention bill, which it did by a slim majority. Johnston had broken with his party on a major issue, and the Birmingham Age-Herald applauded his bravery. Later in 1899, Johnston’s audacity was again evident when he challenged Alabama’s four-term senator John Tyler Morgan for his Senate seat, with the convention call the fundamental question dividing the two contestants.

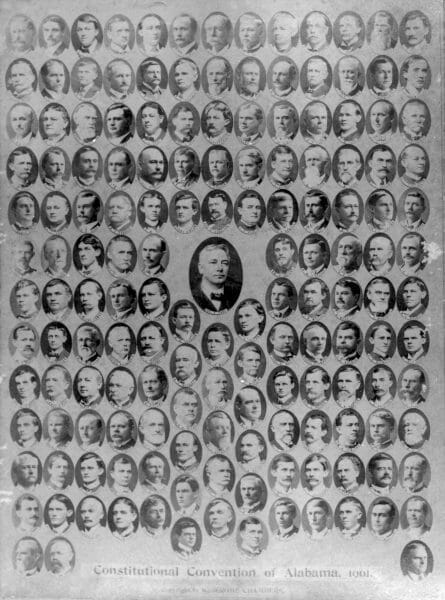

1901 Constitutional Convention

When Morgan won decisively, the convention was called and its primary objective was obtained. The 1901 Constitution disfranchised virtually all of the state’s previously eligible African American voters and a large number of poor and illiterate whites as well. Because the constitution had to be ratified by the voters, Johnston seized on this third and final chance to defeat it. He mobilized his reform coalition but was beaten again, with his opponents engaging in a last bout of electoral fraud to defeat him. In 1900, he insisted that the Democrats nominate their candidate for governor through a primary election. This novel approach originated among reformers and progressives of the early twentieth century who hoped it would dethrone the party machines and managers who controlled the conventions that chose candidates. Although Alabama’s Democratic executive committee felt compelled to concede to a primary, it was still able to control the outcome through its influence over the election machinery and the new and much-reduced electorate. Johnston was once again on the losing side as candidate for governor in 1902, and so was his determined attempt to change the direction of Alabama’s Democratic Party by adopting a reform agenda and winning over the masses of dissatisfied farmers as well as the reformers in the cities and towns.

1901 Constitutional Convention

When Morgan won decisively, the convention was called and its primary objective was obtained. The 1901 Constitution disfranchised virtually all of the state’s previously eligible African American voters and a large number of poor and illiterate whites as well. Because the constitution had to be ratified by the voters, Johnston seized on this third and final chance to defeat it. He mobilized his reform coalition but was beaten again, with his opponents engaging in a last bout of electoral fraud to defeat him. In 1900, he insisted that the Democrats nominate their candidate for governor through a primary election. This novel approach originated among reformers and progressives of the early twentieth century who hoped it would dethrone the party machines and managers who controlled the conventions that chose candidates. Although Alabama’s Democratic executive committee felt compelled to concede to a primary, it was still able to control the outcome through its influence over the election machinery and the new and much-reduced electorate. Johnston was once again on the losing side as candidate for governor in 1902, and so was his determined attempt to change the direction of Alabama’s Democratic Party by adopting a reform agenda and winning over the masses of dissatisfied farmers as well as the reformers in the cities and towns.

Joseph F. Johnston’s attempt to move the Democrats away from their economic and financial conservatism and toward the center of the political spectrum was insightful in conception and bold in its execution. But it failed decisively, and the conservative faction consolidated its hold on the party until 1907, when, at the height of the Progressive movement, Braxton Bragg Comer became governor and the Democrats briefly embraced reform. And although Johnston opposed the disfranchising convention, he did not have very enlightened views about race. He was a reformer, but his views about African Americans were little different from those of the men who actually carried disfranchisement out.

Despite his lengthy fight with the conservatives, Johnston remained an influential figure within the Democratic Party. Just before the state’s octogenarian senators, John T. Morgan and Edmund W. Pettus, died in 1907, the party held an unusual primary, jokingly called the “dead shoes” primary, to choose their successors. Johnston received the second highest number of votes, and so he took Pettus’s seat, with John H. Bankhead succeeding Morgan. Johnston’s five years in Washington were not marked by any significant accomplishments, and he died in office on August 8, 1913. He is buried Elmwood Cemetery in Birmingham.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Fry, Joseph A. John Tyler Morgan and the Search for Southern Autonomy. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992.

- McMillan, Malcolm C. Constitutional Development in Alabama, 1798-1901: A Study in Politics, the Negro, and Sectionalism. 1955. Reprint, Spartanburg, S.C.: Reprint Co., 1978.

- Perman, Michael. Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888-1908. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.