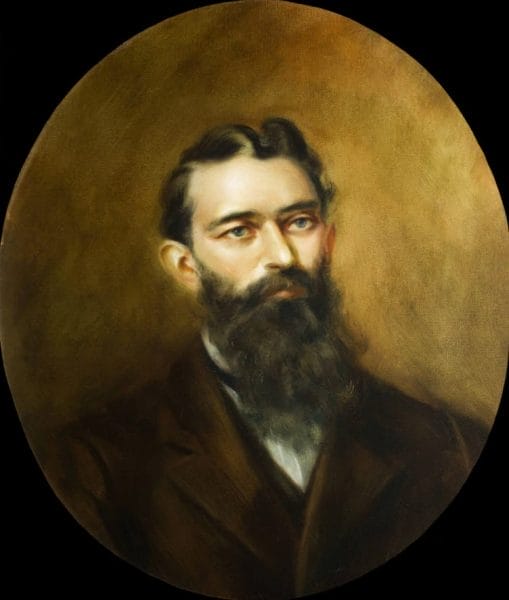

Thomas Seay (1886-90)

Thomas Seay

Thomas Seay (1846-1896) was Alabama‘s governor from 1886 to 1890, years when frustration at Bourbon rule began to boil over. He was a Confederate veteran, served in the state Senate for 10 years, and as governor took an active role in funding education, though he had a mixed record regarding other progressive ideals.

Thomas Seay

Thomas Seay (1846-1896) was Alabama‘s governor from 1886 to 1890, years when frustration at Bourbon rule began to boil over. He was a Confederate veteran, served in the state Senate for 10 years, and as governor took an active role in funding education, though he had a mixed record regarding other progressive ideals.

Born to Reuben and Ann McGee Seay on November 20, 1846, the future governor spent his boyhood on a plantation in Greene (later Hale) County. In 1858, his family moved to Greensboro, where he subsequently began his higher education at Southern University (which later merged with Birmingham College to create Birmingham-Southern College). Secession and the Civil War interrupted his studies, however. In 1863, Seay enlisted and served as a private in the Confederate Army. He saw action in skirmishes around Mobile at Spanish Fort and Fort Blakeley and had the ill-fortune to be captured and imprisoned on Ship Island near Alabama’s port city.

Having survived war and brief incarceration, young Seay returned to his studies at Southern University and graduated in 1867. He read law, was admitted to the Alabama State Bar, and settled down to the dual pursuits typical of his southern gentleman class: practicing law in Greensboro and growing cotton in Hale County. In 1874, at the age of 28, he ran unsuccessfully for the Alabama Senate, but two years later he was elected to that body. He served for 10 years and was president of the Senate from 1884 to 1886. He married Ellen Smaw of Greene County in 1875, and the couple had two children before her death in 1879. Two years later, he married Clara de Lesdernier, with whom he had four more children.

By the time the Democratic convention met in June 1886, delegates confronted a four-man race for governor. Seay was a dark-horse candidate who nonetheless was supported by the politicians and industrial interests of Birmingham, Anniston, and Sheffield. After the 10th ballot, Seay gained strength, and on the 30th ballot the other candidates withdrew. Seay was nominated for governor by acclamation. The divisive Democratic convention revealed a growing factionalism within the party between the state’s industrial-planter interests and small farmers. Seay was elected governor with 145,095 votes, against 37,118 for Republican Arthur Bingham and 576 for Prohibition candidate John T. Tanner. Although his political views did not differ substantially from his recent Bourbon predecessors, Seay’s nomination was viewed as a victory of a younger politician over the older and better-known Bourbon politicians. Seay’s $3,000 salary, the same as that received by his predecessors, was among the lowest in the South, along with those of North Carolina and Georgia.

Seay compiled an interesting and sometimes ambiguous record. He took an aggressive stance against lynching, angering the sheriff of Lauderdale County with his protest of an incident there. He opposed the Prohibition movement and asserted that the issue was a moral one that should not be politicized. Seay also supported legislation restricting the labor of women and children not yet 18 to eight hours a day, the first such act passed by a southern state. Legislators in the next session exempted two textile-mill counties from the act, however, and in 1894 the never-enforced-bill was repealed. Seay was the first Alabama governor to use state funds to provide small pensions for disabled Confederate veterans or the widows of slain Confederates.

Alabama School for Negro Deaf and Blind

Ultimately, Seay is best remembered for his support of education. He endorsed the controversial Blair Education Bill, a proposal in the U.S. Congress to grant federal funds for education to states on the basis of their illiteracy rates. His position ran counter to Alabama’s powerful and popular senator John Tyler Morgan, who opposed it, fearing that it would lead to federal control of education. Seay further supported an appropriation for improvements in agricultural education at the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Alabama (now Auburn University) and urged the founding of a school for deaf African Americans, which the legislature approved in 1891 as part of the Alabama Institute for the Deaf and Blind. He oversaw the establishment of the Normal School at Troy (now Troy University) and the Normal School for Colored Students in Montgomery (now Alabama State University). He supported increased but cautious expenditures to education and simultaneously, and in good Bourbon fashion, lowered the tax rate and ended his term of office with a surplus in the treasury from added revenues that came from improved property value.

Alabama School for Negro Deaf and Blind

Ultimately, Seay is best remembered for his support of education. He endorsed the controversial Blair Education Bill, a proposal in the U.S. Congress to grant federal funds for education to states on the basis of their illiteracy rates. His position ran counter to Alabama’s powerful and popular senator John Tyler Morgan, who opposed it, fearing that it would lead to federal control of education. Seay further supported an appropriation for improvements in agricultural education at the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Alabama (now Auburn University) and urged the founding of a school for deaf African Americans, which the legislature approved in 1891 as part of the Alabama Institute for the Deaf and Blind. He oversaw the establishment of the Normal School at Troy (now Troy University) and the Normal School for Colored Students in Montgomery (now Alabama State University). He supported increased but cautious expenditures to education and simultaneously, and in good Bourbon fashion, lowered the tax rate and ended his term of office with a surplus in the treasury from added revenues that came from improved property value.

Had these actions comprised the total of Seay’s administrations, the young governor would be remembered for sharing many of the same progressive instincts of then-President Grover Cleveland, who visited Alabama in 1887. In counterpoint to these apparently progressive stands, however, Seay took positions that were typically Bourbon. Although he appointed Reuben F. Kolb as state commissioner of agriculture (and who later emerged as Alabama’s most famous Populist), Seay was no friend to the agrarian movement when its leaders looked to the state for relief during desperate economic times. In fact, Seay demonstrated his abiding conservatism when he reconsidered his acceptance of an invitation to speak to the 1889 Farmers Alliance Convention in Montgomery in a pointed display of his unhappiness with that group’s drift toward politics.

Pratt Company Mining Camp

In a similarly Bourbon action, Seay backed the interest of one of the state’s largest companies in a dispute over the convict-lease system. In 1888, a 10-year exclusive contract for convict labor was awarded to the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company (TCI), new owners of the Pratt mines, where the state’s prisoners were normally leased. Losing bidders protested the award, and a legislative committee found that TCI had not made the highest bid, nor were they taking the requisite number of convicts. Legislators recommended that the governor nullify the contract, which cost the state badly needed revenue, but Seay backed the company when it promised to live by the terms of its legal agreement with the state. TCI increased its payment for the convicts, but the state never required the company to follow all the terms of the contract. In 1888, Birmingham was the scene of a riot when two thousand men stormed the jail with the intent of hanging Richard Hawes for murdering his wife and two small daughters. Seay sent in state troops to maintain law and order, and the developing and prospering mineral district of Birmingham and Bessemer applauded his strong action.

Pratt Company Mining Camp

In a similarly Bourbon action, Seay backed the interest of one of the state’s largest companies in a dispute over the convict-lease system. In 1888, a 10-year exclusive contract for convict labor was awarded to the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company (TCI), new owners of the Pratt mines, where the state’s prisoners were normally leased. Losing bidders protested the award, and a legislative committee found that TCI had not made the highest bid, nor were they taking the requisite number of convicts. Legislators recommended that the governor nullify the contract, which cost the state badly needed revenue, but Seay backed the company when it promised to live by the terms of its legal agreement with the state. TCI increased its payment for the convicts, but the state never required the company to follow all the terms of the contract. In 1888, Birmingham was the scene of a riot when two thousand men stormed the jail with the intent of hanging Richard Hawes for murdering his wife and two small daughters. Seay sent in state troops to maintain law and order, and the developing and prospering mineral district of Birmingham and Bessemer applauded his strong action.

Seay was an interesting blend of old values and new directions. The reign of the Bourbons was about to undergo its first major challenge—not an ephemeral changing of the guard but a major effort to alter the content and beneficiaries of public action. At the very time that Alabama’s mining and manufacturing concerns grew and prospered, its small farmers struggled for survival. In reaction and counterpoint to their economic woes, those farmers cast about for causes and for cures, including organizing the Grange, the Wheel, and the Farmers Alliance, and then aligning with the Populist Party and the Jeffersonian Democrats. As the winds of the Populist revolt blew around him, Seay bent with them but was never swept away from the old moorings of the state Democratic Party.

In 1890, Seay was defeated in his bid for a U.S. Senate seat. He did not run for office again and died at the age of 49 on March 30, 1896, in Greensboro, where he is interred at City Cemetery.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Going, Allen Johnston. Bourbon Democracy in Alabama, 1874-1890. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1951.

- Rogers, William W. The One-Gallused Rebellion: Agrarianism in Alabama, 1865-1896. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1970.

- Rogers, Willliam W., et al. Alabama, The History of a Deep South State. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994.