Presidential Race of 1928

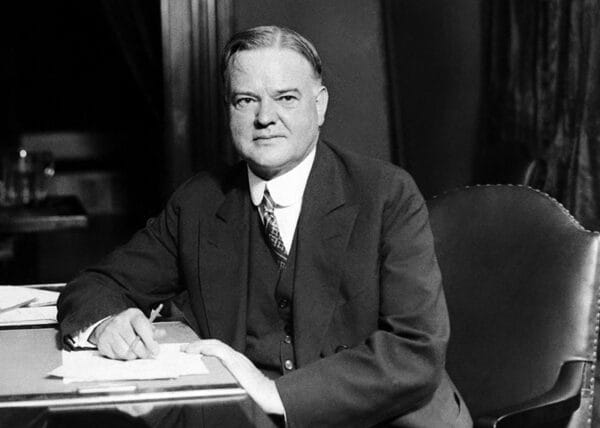

Herbert Hoover

The presidential election of 1928 was one of the most controversial in American history, providing a major test of party loyalties in Alabama, which had historically voted Democratic. The controversy surrounded the issues of Prohibition, religion, race, the Republican prosperity, and a distrust of urban politicians. Many scholars maintain that 1928 was a realigning election in which traditional party bases switched loyalties to the extent that the makeup of both parties was transformed. In Alabama, however, voters continued to support Democratic candidates by large majorities, voting for Franklin Roosevelt by margins of more than 80 percent between 1932 and 1944.

Herbert Hoover

The presidential election of 1928 was one of the most controversial in American history, providing a major test of party loyalties in Alabama, which had historically voted Democratic. The controversy surrounded the issues of Prohibition, religion, race, the Republican prosperity, and a distrust of urban politicians. Many scholars maintain that 1928 was a realigning election in which traditional party bases switched loyalties to the extent that the makeup of both parties was transformed. In Alabama, however, voters continued to support Democratic candidates by large majorities, voting for Franklin Roosevelt by margins of more than 80 percent between 1932 and 1944.

Both major candidates, Democrat Alfred E. Smith and Republican Herbert Hoover, came from similar backgrounds and expressed many of the same views. In 1928, Herbert Hoover was one of the most respected men in America. He had served as the United States Food Administrator during World War I and as the Commissioner for Belgian Relief to aid that country while occupied by Imperial Germany. As the leader of the American Relief Commission, Hoover oversaw post-war recovery efforts in Europe. He turned down the Republican nomination in 1920 but served the country as Secretary of Commerce from 1921 to 1928. The Irish-Catholic Smith was the popular four-term governor of New York who had instituted a number of successful reforms, including appointing women to significant positions, instituting policies aimed at improving education, child welfare, and care of the mentally ill, and ending the state’s system of pork-barrel politics.

Alfred E. Smith

One of the most important issues at the time was Prohibition, which had taken effect in January 1920, banning the sale, manufacture, and transportation of all beverages containing more than 0.5 percent alcohol. Al Smith, the Democratic candidate, opposed the ban on alcohol on the grounds that the issue should be decided at the state level. Hoover, the Republican candidate, was an advocate of Prohibition. Alabama was considered a “dry” state, bringing the state Democratic Party into direct conflict with the national party’s support for Smith.

Alfred E. Smith

One of the most important issues at the time was Prohibition, which had taken effect in January 1920, banning the sale, manufacture, and transportation of all beverages containing more than 0.5 percent alcohol. Al Smith, the Democratic candidate, opposed the ban on alcohol on the grounds that the issue should be decided at the state level. Hoover, the Republican candidate, was an advocate of Prohibition. Alabama was considered a “dry” state, bringing the state Democratic Party into direct conflict with the national party’s support for Smith.

Even more than his stand on Prohibition, Smith was opposed by Democratic Alabamians on two highly volatile personal issues: religion and race. Many Americans were convinced that a Smith victory would lead to Roman Catholic domination of the United States. Anti-Catholicism was particularly strong in the South, where many ministers sought to convince their congregations that Smith was evil and un-Christian. In response to the anti-Catholic fervor, Alabama created a commission to investigate charges that Catholic nuns were holding Protestant girls prisoner. In neighboring Florida, the governor announced that the Pope had his bags packed and was ready to take over the state if Al Smith won the election. Hoover supporters in the South also hoped to play on white southerners’ racial prejudices, insisting that Smith favored African Americans over white southerners and accusing him of favoring intermarriage. Smith was also vilified for his stand against the Ku Klux Klan.

J. Thomas Heflin

Thomas Heflin, the junior senator from Alabama, aroused anti-Smith fervor through speeches and pamphlets. Heflin denounced Democrats who voted party lines rather than choosing candidates based on their stands on issues. He claimed that such party members would vote for a “yellow dog” if it ran on the Democratic ticket, giving rise to the label of “Yellow-Dog Democrats,” which became popular as a negative term for describing southerners who remained staunchly loyal to the party, no matter the candidate.

J. Thomas Heflin

Thomas Heflin, the junior senator from Alabama, aroused anti-Smith fervor through speeches and pamphlets. Heflin denounced Democrats who voted party lines rather than choosing candidates based on their stands on issues. He claimed that such party members would vote for a “yellow dog” if it ran on the Democratic ticket, giving rise to the label of “Yellow-Dog Democrats,” which became popular as a negative term for describing southerners who remained staunchly loyal to the party, no matter the candidate.

Both Smith and Hoover were accused of having been involved to some extent in political scandals. For Smith, it was his direct connection with Tammany Hall, the New York political machine. For Hoover, it was his party’s responsibility for the Teapot Dome scandal, in which a number of prominent politicians had been accused of manipulating illegal oil reserve deals.

In addition, Alabamians and other southerners were suspicious of Al Smith’s “big city” ways, which were generally viewed as both sophisticated and sinful and disrespectful of southern family values. Smith actively campaigned throughout the country. His informal style was in direct contrast to Hoover’s statesman-like conduct. Hoover delivered only eight campaign speeches in 1928, content to rely on his reputation as a strong executive and humanitarian and ride the wave of Republican economic prosperity.

Hoover supporters employed typical election-year rhetoric and tactics by asserting that a Democratic victory would signal a return to hard times. They also managed to raise a good deal of anti-Democratic fervor by claiming that Pres. Woodrow Wilson had plunged the nation into the European war to serve the interests of himself and those of the Democratic Party. In addition, wealthy Republicans financed the anti-Smith campaign and in Alabama, the state Republican chairman distributed more than 200,000 copies of anti-Catholic pamphlets to promote a Hoover victory. By the time the Republican national convention met in Kansas City, Missouri, in early June, all but one of Alabama’s delegates supported Hoover. When the Democratic Party met in Houston, Texas, in late June, all 24 of the state’s delegates opposed Smith.

On election night, November 6, 1928, Smith barely triumphed over Hoover in Alabama, with 127,797 votes to 120,725, carrying the state by 51.33 percent. Alabama’s 12 electoral votes were allotted to Smith under the winner-take-all system. But Hoover was able to win considerable support in Alabama’s northeast industrial counties and in several southern counties, whereas Smith won the counties in the Black Belt region.

Nationally, the returns revealed a landslide victory for Hoover, who won the popular vote by 21,427,123 (58.2 percent) compared with 15,015,464 (40.8 percent) for Smith. The landslide was even more significant in the Electoral College, with 444 votes for Hoover and 87 for Smith. The remainder of the popular vote was spread among Socialist Party candidate Norman Thomas, and Communist Party candidate William Foster. In addition to Alabama, Smith carried only Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Arkansas, and Georgia, as well as South Carolina, Mississippi, and Louisiana by more than 80 percentage points each. The other states of the former Confederacy deserted the Democratic Party for the first time since Reconstruction. Despite the loss of the election, the Democrats carried most of the nation’s large cities for the first time, a result that would recur in many subsequent elections.

Delivering his inaugural address on March 4, 1929, President Hoover promised Americans that he would lead the country through four more years of prosperity and freedom, but was unable to deliver on the former. On October 29, 1929, the stock market crashed, plunging the country into the Great Depression. Hoover’s insistence that the national government had no responsibility for providing direct aid to unemployed, hungry, and desperate Americans paved the way for the Democratic victory of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932. As a result, Democrats controlled the White House from 1933 until 1952 when voters returned a Republican, Dwight D. Eisenhower, to the presidency. In 1960, the only other Irish Catholic Democrat to run for president, John F. Kennedy, took the White House with only partial help from Alabama. The state gave six electoral votes to non-declared Harry Byrd of Virginia, a conservative Democrat opposed to integration, and began Alabama’s shift toward the Republican Party.

Additional Resources

Andersen, Kristi. The Creation of a Democratic Majority, 1928-1936. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979.

Craig, Douglas B. After Wilson: The Struggle for the Democratic Party, 1920-1934. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

Key, V. O., Jr. The Responsible Electorate. New York: Random House, 1966.

Licht, Allan J. Prejudice and the Old Politics: The Presidential Election of 1928. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979.

Peel, Roy V. and Thomas C. Donnelly. The 1928 Campaign: An Analysis. New York: Richard R. Smith, 1931.