John Hollis Bankhead

John Hollis Bankhead

In addition to serving as a soldier, state legislator, and prison warden, John Hollis Bankhead (1842-1920) was a member of the U.S. Congress for 33 years—first in the House of Representatives and later in the Senate. Bankhead was also a farmer, a businessman, and the patriarch of a family that spawned many other famous Alabamians, including sons and fellow politicians John H. Bankhead II and William B. Bankhead; daughter and state archivist Marie Bankhead Owen; grandson and politician and businessman Walter William Bankhead; and granddaughter Tallulah Bankhead, a star of the stage and screen.

John Hollis Bankhead

In addition to serving as a soldier, state legislator, and prison warden, John Hollis Bankhead (1842-1920) was a member of the U.S. Congress for 33 years—first in the House of Representatives and later in the Senate. Bankhead was also a farmer, a businessman, and the patriarch of a family that spawned many other famous Alabamians, including sons and fellow politicians John H. Bankhead II and William B. Bankhead; daughter and state archivist Marie Bankhead Owen; grandson and politician and businessman Walter William Bankhead; and granddaughter Tallulah Bankhead, a star of the stage and screen.

John Hollis Bankhead was born on the family plantation near old Moscow in present-day Lamar County (formerly within Marion County), on September 13, 1842. Today, his birthplace lies within the town of Sulligent. His parents, James Greer Bankhead and Susan Hollis, originally hailed from South Carolina. The future senator attended local schools and at age 19 joined the Confederate Army as a private in Alabama‘s Sixteenth Infantry Regiment, Company K. He fought in many well-known battles, including Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and Perryville, Kentucky, was wounded several times, and rose to the rank of captain. According to some accounts, Bankhead joined the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction.

Marie and Tallulah Bankhead

After the Civil War, Bankhead turned to farming and politics. On November 13, 1866, he married Tallulah Brockman of Greenville, South Carolina, and together they raised five children: John, William, Louise, Marie, and Henry. Bankhead served three terms in the state legislature, representing Marion County in the state House of Representatives from 1865 to 1867, the Twelfth Senatorial District in the state Senate from 1876 to 1877, and returned to the House to represent Lamar County from 1880 to 1881. In between terms in the legislature Bankhead managed Prairie Lawn, his uncle’s plantation in Noxubee County, Mississippi.

Marie and Tallulah Bankhead

After the Civil War, Bankhead turned to farming and politics. On November 13, 1866, he married Tallulah Brockman of Greenville, South Carolina, and together they raised five children: John, William, Louise, Marie, and Henry. Bankhead served three terms in the state legislature, representing Marion County in the state House of Representatives from 1865 to 1867, the Twelfth Senatorial District in the state Senate from 1876 to 1877, and returned to the House to represent Lamar County from 1880 to 1881. In between terms in the legislature Bankhead managed Prairie Lawn, his uncle’s plantation in Noxubee County, Mississippi.

Bankhead, John Hollis

In 1881, Bankhead lobbied for and attained the position of warden of the state penitentiary in Wetumpka. As warden, he focused on Alabama’s convict-leasing system, which exploited the incarcerated as cheap labor for private industry. Although the system proved lucrative for the state and county governments, conditions for the prisoners were harsh and often deadly. Bankhead considered the state’s system outdated and publicly criticized the appalling conditions in which convicts lived. Medical care was poor, inmates were ill-fed, and housing was usually filthy and inadequate. Bankhead did not call for an end to the brutal system but urged the state legislature to improve conditions. Some scholars have suggested that Bankhead was in collusion with industrial leaders and improved the system for the benefit of industrial profits, but Bankhead’s role in Alabama’s convict-leasing system was much more complicated.

Bankhead, John Hollis

In 1881, Bankhead lobbied for and attained the position of warden of the state penitentiary in Wetumpka. As warden, he focused on Alabama’s convict-leasing system, which exploited the incarcerated as cheap labor for private industry. Although the system proved lucrative for the state and county governments, conditions for the prisoners were harsh and often deadly. Bankhead considered the state’s system outdated and publicly criticized the appalling conditions in which convicts lived. Medical care was poor, inmates were ill-fed, and housing was usually filthy and inadequate. Bankhead did not call for an end to the brutal system but urged the state legislature to improve conditions. Some scholars have suggested that Bankhead was in collusion with industrial leaders and improved the system for the benefit of industrial profits, but Bankhead’s role in Alabama’s convict-leasing system was much more complicated.

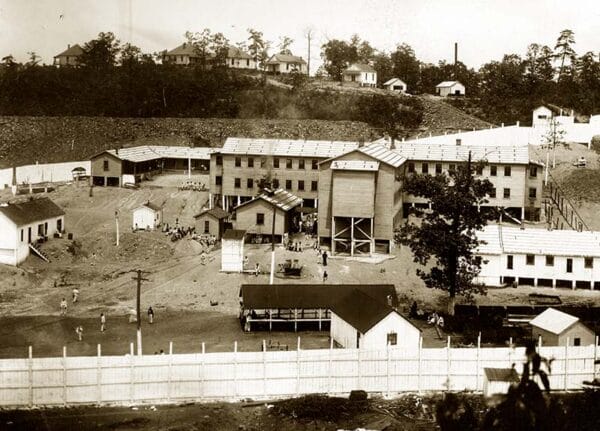

Pratt Company Mining Camp

As a young ambitious politician and future coal operator, Bankhead certainly identified with the state’s industrial leaders, but the letters that he wrote as warden also illustrate a paternalistic concern for the wellbeing of the prisoners and the belief that humane treatment was essential for the reform of individual convicts. He began his tenure by negotiating new contracts with the state’s industrialists, causing one contractor, John W. Comer, to sue for breach of contract. Bankhead continued the existing practice of housing convicts at the contractor’s location, but he advocated reform of this system. He wanted all prisoners to be housed at the penitentiary so that the warden could supervise their labor and living conditions. Various factors, including inadequate space and the need for legislative reform, prohibited Bankhead from making these changes. Although the state legislature did make some improvements in the convict-leasing system during Bankhead’s tenure as warden, there is question whether these reforms actually improved inmates’ lives or conditions. For example, in 1883, the General Assembly gave prison inspectors more authority to report and punish infractions, but there is little evidence that any punishments were ever meted out to guilty contractors. Bankhead did manage to provide better accommodations for convicts who lived at the Pratt Mines, where a majority of the state’s convicts labored. He supervised the construction of a $14,500 segregated facility that included separate hospitals, bathhouses, and dining halls for black and white inmates. In February 1885, the General Assembly re-organized the penitentiary system and abolished the office of warden. Bankhead moved to Fayette, where he resumed farming and went into business with a local merchant.

Pratt Company Mining Camp

As a young ambitious politician and future coal operator, Bankhead certainly identified with the state’s industrial leaders, but the letters that he wrote as warden also illustrate a paternalistic concern for the wellbeing of the prisoners and the belief that humane treatment was essential for the reform of individual convicts. He began his tenure by negotiating new contracts with the state’s industrialists, causing one contractor, John W. Comer, to sue for breach of contract. Bankhead continued the existing practice of housing convicts at the contractor’s location, but he advocated reform of this system. He wanted all prisoners to be housed at the penitentiary so that the warden could supervise their labor and living conditions. Various factors, including inadequate space and the need for legislative reform, prohibited Bankhead from making these changes. Although the state legislature did make some improvements in the convict-leasing system during Bankhead’s tenure as warden, there is question whether these reforms actually improved inmates’ lives or conditions. For example, in 1883, the General Assembly gave prison inspectors more authority to report and punish infractions, but there is little evidence that any punishments were ever meted out to guilty contractors. Bankhead did manage to provide better accommodations for convicts who lived at the Pratt Mines, where a majority of the state’s convicts labored. He supervised the construction of a $14,500 segregated facility that included separate hospitals, bathhouses, and dining halls for black and white inmates. In February 1885, the General Assembly re-organized the penitentiary system and abolished the office of warden. Bankhead moved to Fayette, where he resumed farming and went into business with a local merchant.

John H. Bankhead Home

In 1886, Bankhead defeated one-term Democratic incumbent John Mason Martin to represent Alabama’s Sixth District—which encompassed Fayette, Greene, Jefferson, Lamar, Marion, Pickens, Sumter, Tuscaloosa, Walker, and Winston Counties—in the U.S. House of Representatives and would serve for 20 years. He sat on the Rivers and Harbors Committee and on the Public Buildings and Grounds Committee, which he later chaired. These assignments enabled him to procure funding for the state for buildings and waterways. In 1906, he lost the Democratic primary to Richmond Pearson Hobson, a Spanish-American War hero from Hale County. This setback, however, did not end Bankhead’s congressional career. Later in 1906, Alabama held a Democratic primary for alternate senator. At that time, state legislatures still appointed federal senators. Alabama’s legislature met only every four years, and both of the state’s senators were aging. The state Democratic Party held a primary to choose a successor should one or both of its senators die before the legislature met again. Bankhead won the primary, and in June 1907, upon the death of Sen. John Tyler Morgan, he was appointed to his seat. In 1910, Bankhead moved to Jasper and built a large home, which he named Sunset. He and his sons purchased Caledonia Coal Company, which they renamed Bankhead Coal Company, and he took an active role in the company’s financing, although his son John served as the company’s president.

John H. Bankhead Home

In 1886, Bankhead defeated one-term Democratic incumbent John Mason Martin to represent Alabama’s Sixth District—which encompassed Fayette, Greene, Jefferson, Lamar, Marion, Pickens, Sumter, Tuscaloosa, Walker, and Winston Counties—in the U.S. House of Representatives and would serve for 20 years. He sat on the Rivers and Harbors Committee and on the Public Buildings and Grounds Committee, which he later chaired. These assignments enabled him to procure funding for the state for buildings and waterways. In 1906, he lost the Democratic primary to Richmond Pearson Hobson, a Spanish-American War hero from Hale County. This setback, however, did not end Bankhead’s congressional career. Later in 1906, Alabama held a Democratic primary for alternate senator. At that time, state legislatures still appointed federal senators. Alabama’s legislature met only every four years, and both of the state’s senators were aging. The state Democratic Party held a primary to choose a successor should one or both of its senators die before the legislature met again. Bankhead won the primary, and in June 1907, upon the death of Sen. John Tyler Morgan, he was appointed to his seat. In 1910, Bankhead moved to Jasper and built a large home, which he named Sunset. He and his sons purchased Caledonia Coal Company, which they renamed Bankhead Coal Company, and he took an active role in the company’s financing, although his son John served as the company’s president.

Bankhead, John, Tallulah

As senator, Bankhead served as campaign manager for Alabama senator Oscar Underwood when he sought the 1912 Democratic presidential nomination. He voted against the 19th amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave women the vote, because he considered suffrage to be a matter of state authority and was opposed to federal regulation. Bankhead told his constituents that he would support giving Alabama’s women the right to vote, but only at the state level if the majority of Alabama’s voters agreed. There was an implicit racial motivation to Bankhead’s position on woman suffrage as well. In 1919, white southerners like Bankhead still recalled with contempt the constitutional amendments passed by Congress during Reconstruction. The 15th Amendment prohibiting states from denying suffrage on the basis of race, which enfranchised many African Americans after the Civil War, was held in particular disdain. Although most southern states, including Alabama, circumvented the spirit of the 15th Amendment with literacy tests and poll taxes, many southern politicians still feared that any federal regulation of suffrage would validate future efforts by the national government to encourage black voting in the South, even though African American suffrage was not directly at issue during these debates. Despite Bankhead’s opposition, the 19th amendment passed Congress and was ratified by the states.

Bankhead, John, Tallulah

As senator, Bankhead served as campaign manager for Alabama senator Oscar Underwood when he sought the 1912 Democratic presidential nomination. He voted against the 19th amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave women the vote, because he considered suffrage to be a matter of state authority and was opposed to federal regulation. Bankhead told his constituents that he would support giving Alabama’s women the right to vote, but only at the state level if the majority of Alabama’s voters agreed. There was an implicit racial motivation to Bankhead’s position on woman suffrage as well. In 1919, white southerners like Bankhead still recalled with contempt the constitutional amendments passed by Congress during Reconstruction. The 15th Amendment prohibiting states from denying suffrage on the basis of race, which enfranchised many African Americans after the Civil War, was held in particular disdain. Although most southern states, including Alabama, circumvented the spirit of the 15th Amendment with literacy tests and poll taxes, many southern politicians still feared that any federal regulation of suffrage would validate future efforts by the national government to encourage black voting in the South, even though African American suffrage was not directly at issue during these debates. Despite Bankhead’s opposition, the 19th amendment passed Congress and was ratified by the states.

Good Roads Movement

Although Bankhead opposed federal regulation of suffrage, he favored federal funding for transportation, especially for building roads and developing waterways. He supported improving roadways in order to facilitate mail delivery in rural areas and to help southern farmers transport goods to market. Bankhead also believed that federal and state cooperation was necessary to build and maintain good roads. In 1916, he sponsored federal legislation creating a fund of $200 million that would provide states with matching funds for highway construction. Alabama responded by passing a $25 million highway bond necessary to secure federal funds in 1921, and thus Bankhead’s bill began a tradition of federal and state cooperation to fund roadways. Bankhead also served as president of the United States Good Roads Association and spoke at good roads conferences across the nation. These efforts earned him the nickname “Father of Good Roads.”

Good Roads Movement

Although Bankhead opposed federal regulation of suffrage, he favored federal funding for transportation, especially for building roads and developing waterways. He supported improving roadways in order to facilitate mail delivery in rural areas and to help southern farmers transport goods to market. Bankhead also believed that federal and state cooperation was necessary to build and maintain good roads. In 1916, he sponsored federal legislation creating a fund of $200 million that would provide states with matching funds for highway construction. Alabama responded by passing a $25 million highway bond necessary to secure federal funds in 1921, and thus Bankhead’s bill began a tradition of federal and state cooperation to fund roadways. Bankhead also served as president of the United States Good Roads Association and spoke at good roads conferences across the nation. These efforts earned him the nickname “Father of Good Roads.”

Construction of the Bankhead Tunnel

Bankhead also championed the development of the nation’s waterways. In 1906, Pres. Theodore Roosevelt appointed Bankhead to a position on the Inland Waterways Commission, where he helped to study the most efficient use of the nation’s water resources. Among his congressional achievements in Alabama, he procured funding to construct a dam on the Coosa River to facilitate navigation and water-power generation. He encouraged the construction of a nitrate plant in Muscle Shoals during World War I to manufacture explosives and fertilizer. This project also laid a foundation for the later development of the Tennessee Valley Authority. He also provided Alabama’s coal regions with a water route to international markets through Mobile by securing federal appropriations to develop Mobile Bay and to construct a series of locks and dams on the Warrior River.

Construction of the Bankhead Tunnel

Bankhead also championed the development of the nation’s waterways. In 1906, Pres. Theodore Roosevelt appointed Bankhead to a position on the Inland Waterways Commission, where he helped to study the most efficient use of the nation’s water resources. Among his congressional achievements in Alabama, he procured funding to construct a dam on the Coosa River to facilitate navigation and water-power generation. He encouraged the construction of a nitrate plant in Muscle Shoals during World War I to manufacture explosives and fertilizer. This project also laid a foundation for the later development of the Tennessee Valley Authority. He also provided Alabama’s coal regions with a water route to international markets through Mobile by securing federal appropriations to develop Mobile Bay and to construct a series of locks and dams on the Warrior River.

On March 1, 1920, Bankhead died in Washington, D.C. His body was transported to Jasper and interred at Oak Hill Cemetery. Bankhead’s legacy lies in his commitments to improving waterways and roads. Alabama commemorated these efforts with the Bankhead Bridge, dedicated in April 1930 in Talladega County, which traverses the Coosa River and with the Bankhead Tunnel, opened to traffic in February 1941, which passes under the Mobile River. The nation dedicated the Bankhead National Highway in honor of his efforts on behalf of good roads. Today, travelers can still drive from Washington, D.C., through Bankhead’s hometown of Jasper, and on to San Diego, California, on the highway that bears his name.

Further Reading

- Koster, Margaret Shirley. “The Congressional Career of John Hollis Bankhead.” M.A. Thesis, University of Alabama, 1931.

- Watson, Elbert L. “John Hollis Bankhead, Sr.” In Alabama United States Senators, 95-98. Huntsville, Ala.: Strode Publishers, 1982.

- Weingroff, Richard F. “Federal Aid Road Act of 1916: Building the Foundation Sidebars.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration, 2005.