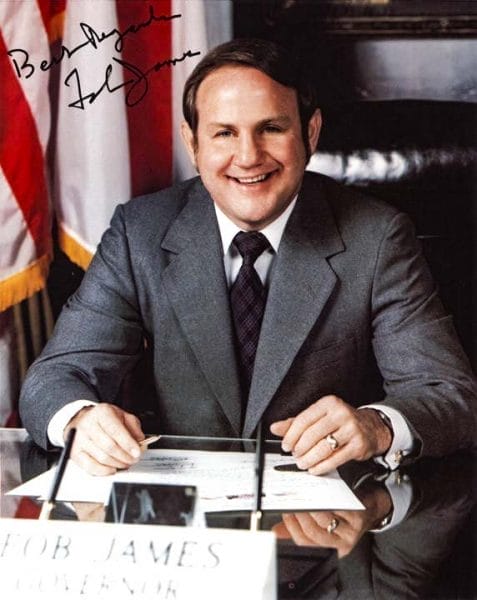

Forrest "Fob" James Jr. (1979-83, 1995-99)

Forrest Hood James Jr.

Forrest Hood “Fob” James Jr. (1934- ) has the distinction of being the only person ever elected governor of Alabama first as a Democrat and then as a Republican. In this respect he is an appropriate transitional figure in Alabama as state politics moved from being dominated by the Democratic Party to a competitive two-party system.

Forrest Hood James Jr.

Forrest Hood “Fob” James Jr. (1934- ) has the distinction of being the only person ever elected governor of Alabama first as a Democrat and then as a Republican. In this respect he is an appropriate transitional figure in Alabama as state politics moved from being dominated by the Democratic Party to a competitive two-party system.

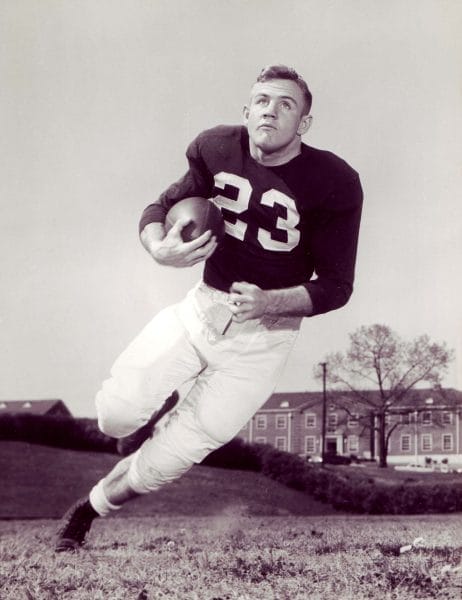

Fob James was born on September 15, 1934, in Lanett, Chambers County, to Forrest Hood “Fob” James Sr. and Rebecca Ellington James. He and his father (and his son and grandson) bear the names of the Confederate generals Nathan Bedford Forrest and John Bell Hood. James attended public schools in Lanett and West Point, Georgia, before transferring to the private Baylor Military Academy in Chattanooga, Tennessee, when he was a sophomore in high school. James returned to Alabama in 1952 and enrolled in Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University), where he played football for Coach Ralph “Shug” Jordan‘s Tigers. A talented athlete, he was given All-American status by the Movietone and International News Service.

Fob James at AU

He received his bachelor of science degree in civil engineering in 1956. On August 20, 1955, before he entered his senior year at Auburn, he eloped with the school’s homecoming queen, Bobbie May Mooney of Decatur, with whom he later had four sons. Following his graduation, James played professional football for the Montreal Alouettes in the Canadian Football League for one year during the 1956 season. At the termination of his brief football career, the future governor served two years as a lieutenant in the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers. Late in 1958, he and his family moved to Montgomery, where he worked as an earth-moving engineer. In 1959, their second born, Greg, was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis. In need of additional money to pay Greg’s medical bills, James left Montgomery in 1960 to take a job as construction superintendent with a road-paving company in Mobile.

Fob James at AU

He received his bachelor of science degree in civil engineering in 1956. On August 20, 1955, before he entered his senior year at Auburn, he eloped with the school’s homecoming queen, Bobbie May Mooney of Decatur, with whom he later had four sons. Following his graduation, James played professional football for the Montreal Alouettes in the Canadian Football League for one year during the 1956 season. At the termination of his brief football career, the future governor served two years as a lieutenant in the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers. Late in 1958, he and his family moved to Montgomery, where he worked as an earth-moving engineer. In 1959, their second born, Greg, was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis. In need of additional money to pay Greg’s medical bills, James left Montgomery in 1960 to take a job as construction superintendent with a road-paving company in Mobile.

Fob James and Bobbie May Mooney

In 1961, James made his most important career move. He decided that he could earn a profitable living making plastic-coated barbells. With financial support from his father and a wealthy attorney friend, Jacob Walker Jr. of Opelika, the three incorporated Diversified Products in 1962. Starting small, James worked the machines himself, and over the next 15 years the company experienced tremendous growth. When the men sold Diversified Products to the Liggett Group of North Carolina in 1977, it had three plants and sales amounting to about $1 billion annually. James remained associated with the company until he was elected governor in 1978.

Fob James and Bobbie May Mooney

In 1961, James made his most important career move. He decided that he could earn a profitable living making plastic-coated barbells. With financial support from his father and a wealthy attorney friend, Jacob Walker Jr. of Opelika, the three incorporated Diversified Products in 1962. Starting small, James worked the machines himself, and over the next 15 years the company experienced tremendous growth. When the men sold Diversified Products to the Liggett Group of North Carolina in 1977, it had three plants and sales amounting to about $1 billion annually. James remained associated with the company until he was elected governor in 1978.

Politically, James was a nonpartisan conservative who usually affiliated with the Republican Party. Bobbie James was actually the first in the family to go on a ballot, running unsuccessfully on the Republican ticket in 1970 for a post on the Alabama State Board of Education. Her husband, after serving briefly as a member of the State Republican Executive Committee, switched to the Democratic Party in 1977. It was the expedient action of a man who had decided to run for governor in a state that had not elected a Republican in a century.

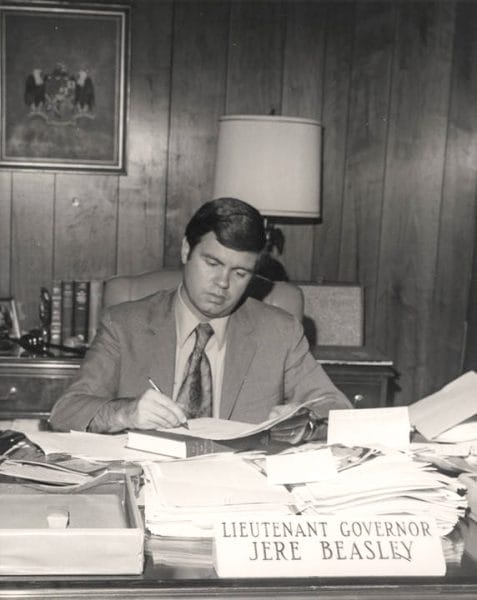

Lt. Gov. Jere Beasley

James set his sights high, and when he made known his aspirations for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination early in 1978, he was given little chance of success. George Wallace, who was at the end of two successive terms, was constitutionally barred from seeking another term. Most political observers thought that the next governor would be either former governor Albert Brewer, Lt. Gov. Jere Beasley, or Attorney General Bill Baxley. In the first balloting on September 5, 1978, however, James’s extensive media advertising paid off, and he easily led the ticket, followed by Baxley, who lagged by some 85,000 votes. In the September 26 runoff, James won the Democratic nomination by an even wider distance. In the general election in November, which was little more than a formality, James defeated former Cullman County probate judge Guy Hunt by a nearly five-to-one margin.

Lt. Gov. Jere Beasley

James set his sights high, and when he made known his aspirations for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination early in 1978, he was given little chance of success. George Wallace, who was at the end of two successive terms, was constitutionally barred from seeking another term. Most political observers thought that the next governor would be either former governor Albert Brewer, Lt. Gov. Jere Beasley, or Attorney General Bill Baxley. In the first balloting on September 5, 1978, however, James’s extensive media advertising paid off, and he easily led the ticket, followed by Baxley, who lagged by some 85,000 votes. In the September 26 runoff, James won the Democratic nomination by an even wider distance. In the general election in November, which was little more than a formality, James defeated former Cullman County probate judge Guy Hunt by a nearly five-to-one margin.

Alabama’s new governor was inaugurated for his first term on January 15, 1979, and won immediate and widespread approval when he declared in his inaugural address that he “claim(ed) for all Alabamians a New Beginning (his campaign theme) free from racism and discrimination.” During his first term as governor, he named Oscar W. Adams to fill a vacancy on the Alabama Supreme Court, the first African American chosen for such a position. In addition, he appointed other blacks to cabinet positions, including Gary Cooper as director of the Department of Pensions and Security, the first African American to be named to head a major state agency in Alabama in a century.

Forrest “Fob” and Bobbie James

Despite such auspicious beginnings, James’s lack of experience was immediately observable. He did not attempt to organize the legislature as previous governors had done and often found himself defeated by the “unmanaged” body. Nor did he focus on a limited agenda; instead, he attempted to push through numerous programs simultaneously. The legislature rejected his proposal for a new constitution and also turned down his recommendation that they stop earmarking state funds, the process by which legislators assigned specific tax revenues for particular projects. James’s first administration inherited serious economic problems from a deep national recession during the late 1970s, and the business-trained governor wanted a freer hand in deciding where state revenues would be expended. With declining revenues, he consolidated state agencies and cut a number of employees from the state payroll. During his first term, the governor angered some and was praised by others because he chose to emphasize funding for K-12 education over that for Alabama’s colleges and universities. As the state’s economic circumstances worsened, James was forced to prorate both the general and education budgets. Proration is a phenomenon in Alabama that occurs when tax revenues fall short of appropriated amounts. Under the state’s balanced budget requirement, funds are cut, forcing schools to complete the academic year with less revenue than anticipated.

Forrest “Fob” and Bobbie James

Despite such auspicious beginnings, James’s lack of experience was immediately observable. He did not attempt to organize the legislature as previous governors had done and often found himself defeated by the “unmanaged” body. Nor did he focus on a limited agenda; instead, he attempted to push through numerous programs simultaneously. The legislature rejected his proposal for a new constitution and also turned down his recommendation that they stop earmarking state funds, the process by which legislators assigned specific tax revenues for particular projects. James’s first administration inherited serious economic problems from a deep national recession during the late 1970s, and the business-trained governor wanted a freer hand in deciding where state revenues would be expended. With declining revenues, he consolidated state agencies and cut a number of employees from the state payroll. During his first term, the governor angered some and was praised by others because he chose to emphasize funding for K-12 education over that for Alabama’s colleges and universities. As the state’s economic circumstances worsened, James was forced to prorate both the general and education budgets. Proration is a phenomenon in Alabama that occurs when tax revenues fall short of appropriated amounts. Under the state’s balanced budget requirement, funds are cut, forcing schools to complete the academic year with less revenue than anticipated.

James was also thwarted when he asked legislators to decentralize state government and give home rule to counties and cities so that they could determine their own futures. Frustrated and not given to compromise, James reacted to these legislative defeats with outbursts of anger. Still, he was often his own worst enemy, and his inattention to detail led to embarrassing mistakes. A package of 20 anticrime bills, which he persuaded a special session of the legislature to enact in 1982, did not become law because his office failed to deliver them to the secretary of state within the required 10-day period. Later court decisions upheld the strict interpretation of this requirement for prompt delivery.

In other areas, however, James was more successful. Early in his first administration, the governor won praise beyond Alabama’s borders for the cooperative stances he frequently took in relation to the federal government, a sharp contrast to Wallace’s confrontational style. James also was more sympathetic to federal judicial efforts in the areas of mental health and prisons and to federal executive efforts to ensure the viability of the Medicaid program.

The issue of religion in the public arena was a prominent issue in both of James’s terms as governor. In 1982, the legislature passed a bill that encouraged voluntary prayer in the state’s public schools, and it included a suggested prayer written by the governor’s son, Fob James III. James’s official biographer, Sandra Baxley Taylor, reported that James did so at his wife’s urging. James’s efforts regarding prayer in public schools were thwarted but did not dissuade him from similar battles on the subject during his second term.

Jim Folsom Jr. and Family

James’s decision not to run again for governor in 1982 eased the way for George Wallace to return to office for a fourth and final term. Out of office, however, James began to yearn for a return to the governorship, and in both the 1986 and 1990 Democratic primaries was badly defeated in both races. Living a semi-retired life while out of office, he partnered with his sons in several businesses, including a marina, a solid-waste disposal firm, and a company that worked to prevent coastal erosion. In the spring of 1994, James’s desire to be governor led him to switch parties one more time, and he qualified at the last moment as a Republican candidate. In the June 7 first balloting, state senator Ann Smith Bedsole of Mobile forced James into a runoff, but on June 28 he defeated her decisively. In the November general election, James ran against the incumbent Democratic governor, Jim Folsom Jr., who had succeeded to that office on the ethics conviction and forced removal from office of Guy Hunt. James stressed ethics and repeatedly reminded voters that Folsom and his associates were under investigation for alleged illegal conduct. He also pledged that he would support no new taxes if he were given another term of office. Folsom, on the other hand, stressed economic development, especially his leadership in attracting the Mercedes-Benz company to Alabama. With integrity as an issue, low voter turnout in rural Democratic strongholds, and unusually high voter turnout in Republican suburbs, James defeated Folsom by a narrow margin and won his second term as governor, this time as a Republican. James also benefited from the national Republican landslide that gave the GOP control of Congress for the first time in 40 years.

Jim Folsom Jr. and Family

James’s decision not to run again for governor in 1982 eased the way for George Wallace to return to office for a fourth and final term. Out of office, however, James began to yearn for a return to the governorship, and in both the 1986 and 1990 Democratic primaries was badly defeated in both races. Living a semi-retired life while out of office, he partnered with his sons in several businesses, including a marina, a solid-waste disposal firm, and a company that worked to prevent coastal erosion. In the spring of 1994, James’s desire to be governor led him to switch parties one more time, and he qualified at the last moment as a Republican candidate. In the June 7 first balloting, state senator Ann Smith Bedsole of Mobile forced James into a runoff, but on June 28 he defeated her decisively. In the November general election, James ran against the incumbent Democratic governor, Jim Folsom Jr., who had succeeded to that office on the ethics conviction and forced removal from office of Guy Hunt. James stressed ethics and repeatedly reminded voters that Folsom and his associates were under investigation for alleged illegal conduct. He also pledged that he would support no new taxes if he were given another term of office. Folsom, on the other hand, stressed economic development, especially his leadership in attracting the Mercedes-Benz company to Alabama. With integrity as an issue, low voter turnout in rural Democratic strongholds, and unusually high voter turnout in Republican suburbs, James defeated Folsom by a narrow margin and won his second term as governor, this time as a Republican. James also benefited from the national Republican landslide that gave the GOP control of Congress for the first time in 40 years.

Gov. Forrest James Official Portrait

James had been out of office for 12 years and was only the second Republican governor in modern times. In some areas the governor replicated the policies of his first administration, appointing Aubrey Miller, a black Alabamian, to head the Alabama Tourism Department. He stressed again what he called “fundamental American values” and pressed his consistent support for K-12 education. The legislature joined him in passing an educational reform package known as the James Educational Foundation Act. This important legislation required local school systems that were not already at a minimum level of support to raise local property taxes to 10 mills, and it increased the number of credit hours in academic subjects that students were required to have in order to graduate. This legislation also empowered the state superintendent of education to take control of schools that scored poorly on national achievement tests. It was a remarkable and important feat for James and, more importantly, for the state. Unfortunately, in his quest to improve K-12 education, he stripped funding from the state’s colleges and universities and further strained relations between higher education and the governor’s office.

Gov. Forrest James Official Portrait

James had been out of office for 12 years and was only the second Republican governor in modern times. In some areas the governor replicated the policies of his first administration, appointing Aubrey Miller, a black Alabamian, to head the Alabama Tourism Department. He stressed again what he called “fundamental American values” and pressed his consistent support for K-12 education. The legislature joined him in passing an educational reform package known as the James Educational Foundation Act. This important legislation required local school systems that were not already at a minimum level of support to raise local property taxes to 10 mills, and it increased the number of credit hours in academic subjects that students were required to have in order to graduate. This legislation also empowered the state superintendent of education to take control of schools that scored poorly on national achievement tests. It was a remarkable and important feat for James and, more importantly, for the state. Unfortunately, in his quest to improve K-12 education, he stripped funding from the state’s colleges and universities and further strained relations between higher education and the governor’s office.

James took a predictable “get tough” position on crime and criminals when he and his prison commissioner, Ronald Jones, reinstituted chain gangs for Alabama’s prison inmates. The governor approved other strict policies instituted by Jones but balked at the commissioner’s suggestion that chain gangs be extended to include female prisoners. Alabama’s chain gangs attracted national attention, and a number of other states followed Alabama’s lead in this area. In the summer of 1995, James signed into law a bill that ended Alabama’s requirement that rape victims pay for their own medical examinations, making Alabama the last state in the nation to end this practice. Yet, James’s reputation for distracted and eccentric behavior often overshadowed his positive actions. In a widely reported incident, James remarked that he wished the state’s government ran as well as the Waffle House restaurants he enjoyed frequenting. Editorial observers responded by suggesting that running a state was significantly more complicated than running a restaurant. In a nod to his Christian fundamentalist supporters, he also supported the inclusion of a “warning label” in Alabama biology textbooks regarding the theory of evolution.

Reversing the moderate posture of his first term, James began to reflect an individualistic states’ rights attitude. He refused to accept federal monies from the U.S. Department of Education’s Goals 2000 program because he believed that accepting the money would lead to increased federal involvement and control over the state’s schools. When Secretary of Education Richard Riley promised that the Department of Education would not interfere in the use of the funds, Alabama’s Board of Education ignored the governor’s role and voted to accept the funding and use it to purchase computers for K–12 classrooms. In a similar act, James “seceded” from the National Governors’ Association and was the only head of a state to refuse to attend this organization’s meetings.

Roy Moore

James’s longest and most publicized battle with the federal government came during the controversy surrounding the posting of the Ten Commandments and the offering of a daily prayer in the courtroom of Etowah County judge Roy Moore. In a suit brought by the American Civil Liberties Union, U.S. district court judge Ira DeMent, an appointee of Pres. George H. W. Bush, ordered the removal of the commandment plaque and cessation of the prayers because they violated the First Amendment guarantee of separation of church and state. Moore appealed the decision, and James supported his position, threatening for a brief period to mobilize the Alabama National Guard and use force if necessary to prevent the removal of the Ten Commandments plaque from Moore’s courtroom. In October 1997, Judge DeMent issued another sweeping and controversial order forbidding certain religious practices in DeKalb County’s public schools. James verbally attacked DeMent’s order as yet another illegitimate intrusion by federal courts into local affairs. The judge’s order was, in part, reversed shortly after James left office, allowing students—on their own—to hold religious meetings on school grounds.

Roy Moore

James’s longest and most publicized battle with the federal government came during the controversy surrounding the posting of the Ten Commandments and the offering of a daily prayer in the courtroom of Etowah County judge Roy Moore. In a suit brought by the American Civil Liberties Union, U.S. district court judge Ira DeMent, an appointee of Pres. George H. W. Bush, ordered the removal of the commandment plaque and cessation of the prayers because they violated the First Amendment guarantee of separation of church and state. Moore appealed the decision, and James supported his position, threatening for a brief period to mobilize the Alabama National Guard and use force if necessary to prevent the removal of the Ten Commandments plaque from Moore’s courtroom. In October 1997, Judge DeMent issued another sweeping and controversial order forbidding certain religious practices in DeKalb County’s public schools. James verbally attacked DeMent’s order as yet another illegitimate intrusion by federal courts into local affairs. The judge’s order was, in part, reversed shortly after James left office, allowing students—on their own—to hold religious meetings on school grounds.

Despite controversial statements and actions, James’s standing in public opinion appeared to benefit from the prosperity being enjoyed by the state and nation. When he qualified for a third term as governor in March 1998, the state’s unemployment rate was at its lowest point ever. But the business community and others who had supported James during earlier campaigns were disgruntled with his lack of interest in economic development issues and with his silly antics and provocative language. On various public occasions, he had scratched himself like a monkey, suggested that lobbyists were like French poodles who occasionally needed a “kick in the ass,” and recommended a “good butt-whupping and then a prayer” as the solution to teen crime. The business community blamed his flip-flopping and inattention for the failure to get strengthened tort reform enacted.

James struggled through a bitter Republican primary runoff with Montgomery millionaire businessman Winton Blount III and had little money left to finance the general election campaign. Lt. Gov. Don Siegelman, on the other hand, easily won the Democratic primary on the sole issue of establishing a state lottery to provide college scholarships. James opposed the lottery but had no focused agenda to offer and was defeated. He returned to semiretirement, saying he wanted to spend more time with his children and grandchildren.

James entered politics and was elected governor the first time as an idealistic progressive who sought fundamental reforms of Alabama’s constitutional system. Yet he was, on the whole, an inept politician and failed to get most of his agenda through the legislature. During his second term, James—like George Wallace—seemed distracted from the real issues of economic development and providing adequate funding for education by battles with the federal courts he could not possibly win. His momentous reform of K-12 education made some improvement in the education provided to the state’s children, but this success was obscured unfortunately by his futile battles with the federal government.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Labash, Matt. “God and Man in Alabama.” Weekly Standard (March 2, 1998): 19–25.

- Raimo, John W., ed. Biographical Directory of the Governors of the United States, 1978–1983. Westport, Conn.: Meckler Publishing, 1985.

- Sack, Kevin. “Alabama’s GOP Governor Follows His Own Vision of New South.” New York Times, August 29, 1997.

- Taylor, Sandra Baxley. Governor Fob James: His 1994 Victory, His Incredible Story. 1995. Reprint, Mobile, Ala.: Greenberry Publishing, 1995.