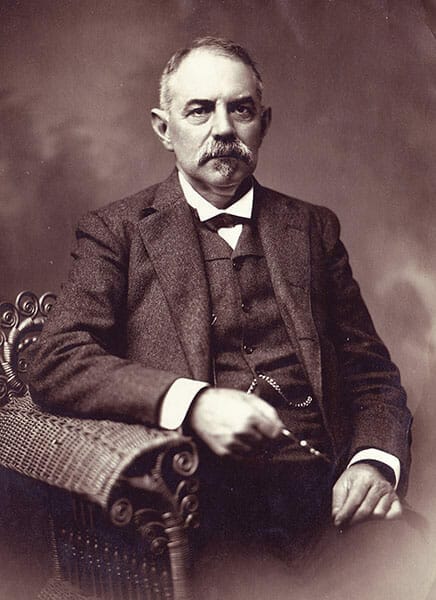

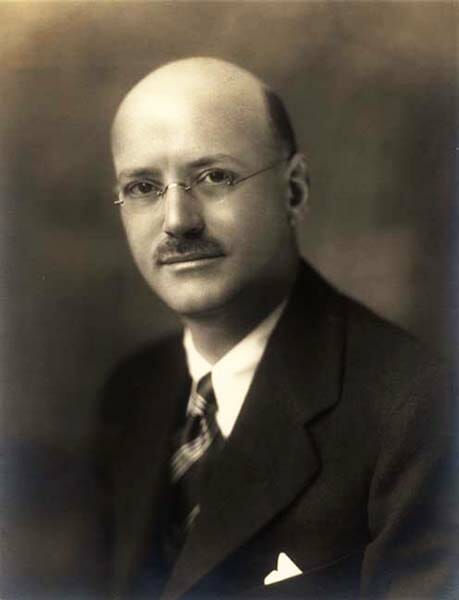

Thomas Goode Jones (1890-94)

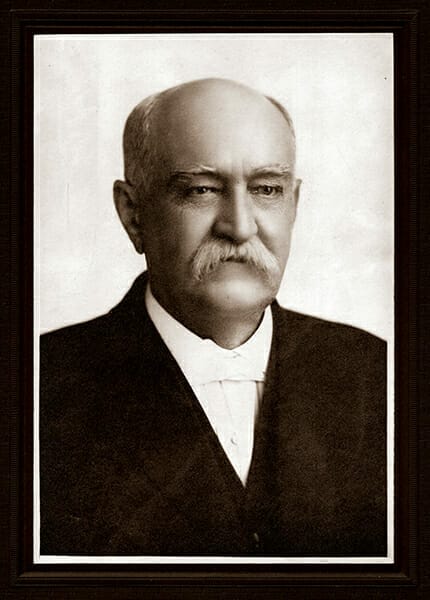

Thomas Goode Jones

Thomas Goode Jones (1844-1914) was one of the most notable Alabama politicians of the post-Civil War era. A Civil War hero, Jones would go on to serve in the legislature, as governor, and as a federal judge. An important supporter of the conservative or “Bourbon” wing of the Democratic Party, Jones was known for independent-minded thought and actions. An aggressive lawyer whose clients included the Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N), he was author of Alabama‘s pioneering 1887 code of legal ethics.

Thomas Goode Jones

Thomas Goode Jones (1844-1914) was one of the most notable Alabama politicians of the post-Civil War era. A Civil War hero, Jones would go on to serve in the legislature, as governor, and as a federal judge. An important supporter of the conservative or “Bourbon” wing of the Democratic Party, Jones was known for independent-minded thought and actions. An aggressive lawyer whose clients included the Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N), he was author of Alabama‘s pioneering 1887 code of legal ethics.

Thomas Goode Jones was born November 26, 1844, in Macon, Georgia. He was the eldest child of Samuel Goode and Martha Ward Goode Jones, both descendants of old Virginia families. Samuel Jones graduated from Williams College, came south in 1839, and embarked on a successful career as a railroad builder in Georgia. In 1850, he moved his family to Montgomery, Alabama, serving as a captain of the home guard during the Civil War.

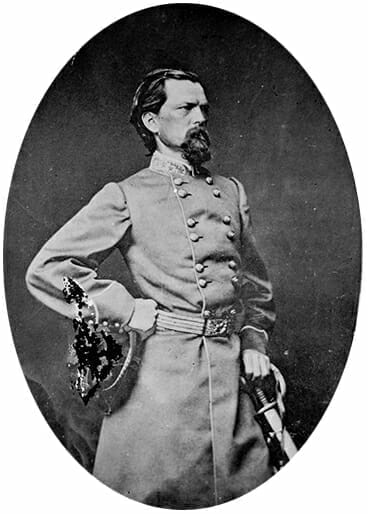

John B. Gordon

Thomas learned ambition and alliance to the South from his father. But this devotion was tempered by support of national industrial development, including railroad construction. Jones attended preparatory schools in Virginia and entered the Virginia Military Institute in the fall of 1860. Like his father, Jones supported the Confederacy, drilling volunteers in Richmond, serving with Stonewall Jackson in the Valley Campaign, aiding Georgia’s John B. Gordon, and finally marching with Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. He was wounded several times, earned promotion to major, and survived to carry a flag of truce through the lines at Appomattox.

John B. Gordon

Thomas learned ambition and alliance to the South from his father. But this devotion was tempered by support of national industrial development, including railroad construction. Jones attended preparatory schools in Virginia and entered the Virginia Military Institute in the fall of 1860. Like his father, Jones supported the Confederacy, drilling volunteers in Richmond, serving with Stonewall Jackson in the Valley Campaign, aiding Georgia’s John B. Gordon, and finally marching with Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. He was wounded several times, earned promotion to major, and survived to carry a flag of truce through the lines at Appomattox.

Jones’s wartime service with Gordon became an important influence in his later life. As a fellow supporter of industrial development in the South, Gordon, a future governor of Georgia, reaffirmed the values Jones’s father had instilled in him. Gordon and Jones each chose careers in law and politics, worked for the L&N, and maintained a close friendship.

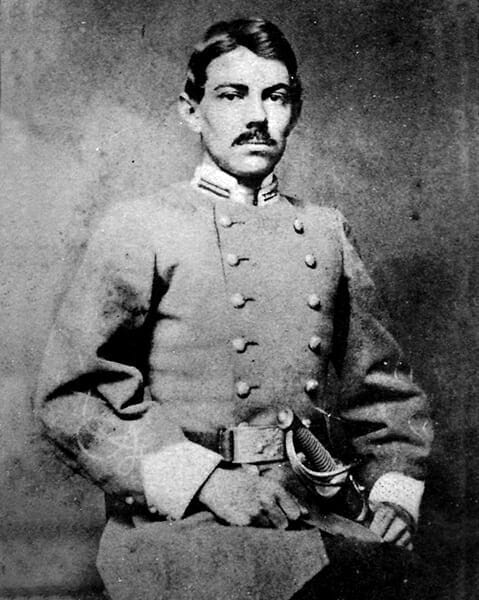

Thomas Goode Jones in Uniform

After the war, Jones returned to Montgomery and began farming cotton on land provided by his father. In 1866, he married Georgena Caroline Bird of Montgomery, with whom he had 13 children. Jones soon decided to leave agriculture and pursue a legal career. He studied under Chief Justice Abram J. Walker and was admitted to the Alabama State Bar in 1868. He also briefly edited The Daily Picayune, a journal for laboring men, in which he criticized post-war Reconstruction efforts by the federal government, but he refrained from attacking the Republicans who directed those efforts. This turned out to be a wise course. Jones ran unsuccessfully for a Democratic alderman seat in Montgomery in 1869 and was hired by the Republican-dominated Alabama Supreme Court the following year as its official reporter, a post that gave him steady work for a decade.

Thomas Goode Jones in Uniform

After the war, Jones returned to Montgomery and began farming cotton on land provided by his father. In 1866, he married Georgena Caroline Bird of Montgomery, with whom he had 13 children. Jones soon decided to leave agriculture and pursue a legal career. He studied under Chief Justice Abram J. Walker and was admitted to the Alabama State Bar in 1868. He also briefly edited The Daily Picayune, a journal for laboring men, in which he criticized post-war Reconstruction efforts by the federal government, but he refrained from attacking the Republicans who directed those efforts. This turned out to be a wise course. Jones ran unsuccessfully for a Democratic alderman seat in Montgomery in 1869 and was hired by the Republican-dominated Alabama Supreme Court the following year as its official reporter, a post that gave him steady work for a decade.

The appointment could not have come at a better time, for by 1870 the unstable cotton market had buried Jones under heavy debt, and he lost his land. And in addition to his work for the Supreme Court, he also spent the 1870s and early 1880s building his law practice and became a trusted advocate for the L&N and other important clients. At the same time, he was gaining a reputation as a moderate politician who was loyal to the Democrats but willing to work with Republicans. In general, he associated with Bourbon Democrats, advocates of limited government and low taxes whose base was primarily in the state’s Black Belt counties—and who, in a loose coalition with businessmen and industrial developers, dominated the Democratic Party for many years.

In 1875, Jones again ran for the alderman position in Montgomery and was successful in his campaign, serving until 1884. Once in office, he focused on issues of public health and prevention of yellow fever outbreaks. In 1874, Jones fully supported Democratic gubernatorial candidate George S. Houston, who promised that he would “redeem” the state from Republican rule and achieve the much-discussed Democratic goal of restoring white supremacy.” Jones also was involved in the organization of state militia units and by 1880 had risen to command of the Second Infantry regiment of state troops.

In 1884, Jones ran successfully for a seat in the Alabama House of Representatives. During this time, he was developing a personal philosophy built from diverse elements: the nationalistic and opportunistic aims of a railroad backer, the respect for legal rights of a lawyer, and the self-conscious paternalism of a former owner of enslaved people toward black citizens. In his role as a member of the legal profession, too, Jones showed concern for the lower classes. A leading member of the Alabama State Bar Association, in 1887 he authored a code of legal ethics (the first state-wide code to be adopted) that made it a lawyer’s duty to protect the poor and powerless and to expose “corrupt or dishonest behavior” in the profession.

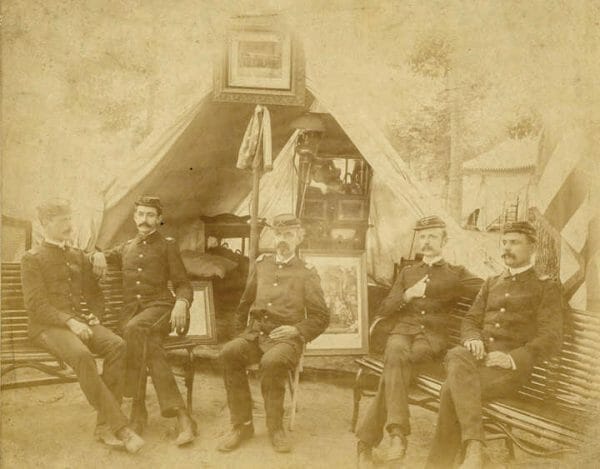

Thomas G. Jones and Montgomery Greys Officers, ca. 1890

As a legislator, Jones was likewise committed to the rule of law. He risked the wrath of white landowners by opposing bills that would have subjected defaulting sharecroppers to forced servitude or imprisonment. He also opposed the operations of the “fee” system, under which sheriffs and other officers leased convicts to industrialists for a fee. These same officials also winked at the brutal practices of local magnates or gave way to lynch mobs. Jones’s response to such events was to work for laws to insure order and due process for all citizens. He also was a willing commander of state troops on several occasions when they were called out to suppress mobs.

Thomas G. Jones and Montgomery Greys Officers, ca. 1890

As a legislator, Jones was likewise committed to the rule of law. He risked the wrath of white landowners by opposing bills that would have subjected defaulting sharecroppers to forced servitude or imprisonment. He also opposed the operations of the “fee” system, under which sheriffs and other officers leased convicts to industrialists for a fee. These same officials also winked at the brutal practices of local magnates or gave way to lynch mobs. Jones’s response to such events was to work for laws to insure order and due process for all citizens. He also was a willing commander of state troops on several occasions when they were called out to suppress mobs.

In 1886, Jones was elected speaker of the house—perhaps for his parliamentary and constitutional expertise—and thereafter his political rise was rapid. The times were tense for the state’s Democrats. Small farmers in Alabama and throughout the South were facing falling cotton prices and high interest rates. Jones knew what it was to be a frustrated farmer, but as a long-time servant of authority he was incapable of challenging the conventional order with regard either to politics or economics. Thus, in the late 1880s, he and many other Democrats were caught by surprise when thousands of small farmers and laborers, both black and white, joined together in such national organizations as the Farmer’s Alliance or the Knights of Labor. The alliance in particular showed farmers how to market cotton without the intervention of bankers, merchants, or large landowners; these and other groups fervently advocated an inflation of the nation’s currency. Jones and many of his fellow legislators saw these “agrarian” groups as foes of the corporations that he had represented in court—corporations that, in his view, had brought prosperity to post-war Alabama.

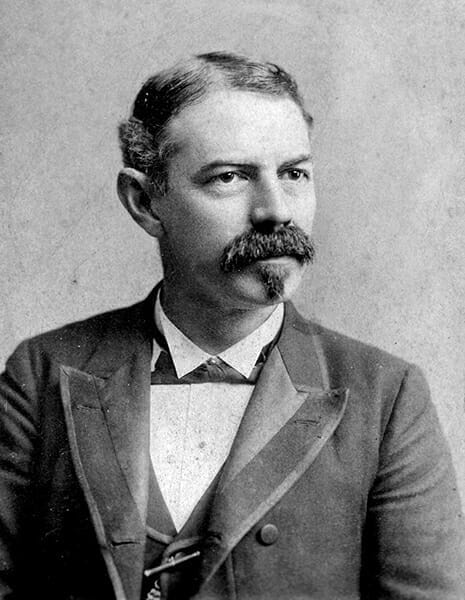

Reuben F. Kolb

In 1890, when the Farmer’s Alliance rallied behind Democratic gubernatorial candidate Reuben F. Kolb, the state’s agriculture commissioner, Jones was one of four conservatives or anti-agrarians who ran in an attempt to stop him and the movement he represented. At the state convention in May, Kolb was close to victory when the anti-Kolb managers decided to pool their votes to defeat him. Jones was the least well-known of the challengers, but his delegates were judged the most likely to switch to Kolb. For this reason and perhaps for his youthful vigor, after three days and 33 ballots Jones was given the nomination. He easily defeated his Republican opponent and took office.

Reuben F. Kolb

In 1890, when the Farmer’s Alliance rallied behind Democratic gubernatorial candidate Reuben F. Kolb, the state’s agriculture commissioner, Jones was one of four conservatives or anti-agrarians who ran in an attempt to stop him and the movement he represented. At the state convention in May, Kolb was close to victory when the anti-Kolb managers decided to pool their votes to defeat him. Jones was the least well-known of the challengers, but his delegates were judged the most likely to switch to Kolb. For this reason and perhaps for his youthful vigor, after three days and 33 ballots Jones was given the nomination. He easily defeated his Republican opponent and took office.

As governor, Jones was often at loggerheads with the legislative branch over his positions on several issues. For instance, few legislators shared his desire to make sheriffs more accountable for lynchings, nor did they appreciate his opposition to their efforts to limit funds to black schools. To his mind, such actions clearly violated the spirit and intent of the Fourteenth Amendment. The governor and the legislature did agree on a bill, passed in 1891, requiring separate but equal accommodations in railroad passenger cars.

Jones’s reform-mindedness was not common among his fellow mainline Democrats. In his second term, he was a relentless opponent of the convict-lease system and enjoyed the support of labor unions, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, former rival Reuben F. Kolb, and a considerable segment of the general public. In response to his efforts, in 1893 the legislature passed a measure by which the state convict authority began to acquire farmland with a view to making state prisons self-supporting. The plan involved transfer of all prisoners from work in Birmingham‘s mines by January 1, 1895. Sadly, the lingering fiscal crisis that followed the Panic of 1893 led to the repeal of the legislation under Jones’s successor, William C. Oates. Indeed, Alabama did not end its convict-lease system until the 1920s, the last U.S. state to do so.

Thomas Goode Jones, ca. 1895

Reform efforts had little to do with Jones’s main task as a party leader—namely, to keep Kolb and the Alliancemen out of power. Kolb had been a good loser in the 1890 election, but two years later he was determined either to win the Democratic gubernatorial nomination or to break the party apart. In spring 1892, fierce battles for delegates raged, and Jones, mindful of and resorting to the Democrats’ long-time racial strategy, spoke out in support of white supremacy. In June, rather than face a second convention defeat, Kolb’s supporters proclaimed him the nominee of the Jeffersonian Democrats. Supported by the newly formed People’s Party (which included the most radical members of the Farmers Alliance and the Knights of Labor) and backed tacitly by Republicans, Kolb and the Jeffersonians challenged Bourbon control of the Black Belt by promising to protect the political rights of blacks.

Thomas Goode Jones, ca. 1895

Reform efforts had little to do with Jones’s main task as a party leader—namely, to keep Kolb and the Alliancemen out of power. Kolb had been a good loser in the 1890 election, but two years later he was determined either to win the Democratic gubernatorial nomination or to break the party apart. In spring 1892, fierce battles for delegates raged, and Jones, mindful of and resorting to the Democrats’ long-time racial strategy, spoke out in support of white supremacy. In June, rather than face a second convention defeat, Kolb’s supporters proclaimed him the nominee of the Jeffersonian Democrats. Supported by the newly formed People’s Party (which included the most radical members of the Farmers Alliance and the Knights of Labor) and backed tacitly by Republicans, Kolb and the Jeffersonians challenged Bourbon control of the Black Belt by promising to protect the political rights of blacks.

Predictably, Democratic journalists and stump-speakers responded with a campaign for white supremacy. Given his efforts to uphold the principles of the Fourteenth Amendment, it is ironic that Jones should have been the standard bearer in such a racist campaign. It likewise was ironic that Kolb, whose party was reaching out to blacks, criticized Jones’ zealous opposition (or over-zealous opposition, from the point of view of white racists) to lynch mobs. The saddest aspect of the election may have been that Jones won it as he did. It was generally agreed that Kolb was defeated by Democratic election officials who stole the votes of black men. Jones reacted to mounting evidence of fraud with anger and denial, filing libel charges against one of his harshest critics, Populist Party editor Frank Baltzell. Shamed and suffering from poor health and financial problems, Jones considered returning to work for the L&N. But his anger against Kolb and the agrarians convinced him to stay in office—and confirmed his belief that the Democratic Party was the rightful, if flawed, guardian of an idealized southern way of life. Despite his support of funding for black schools and desire to end the convict-lease system, Jones bought into his party’s belief in “white supremacy.” In 1893, Jones supported passage of the Sayre Act, which provided for the governor to appoint county registrars and poll officials, insuring they would all be Democrats. Under the act, these officials would maintain voting rolls and “assist” in marking the ballots of illiterate voters. Passage of the Sayre law all but decided the 1894 election in advance—in favor of the Democrats.

During the summer of 1894, his last year as governor, Jones repeatedly sent troops to the Birmingham area to oppose violent strikes by miners and railroad workers whose political loyalties were decidedly Jeffersonian. State convicts and black strikebreakers kept the mines operating. The strike was broken by Jones’s actions, but the link between farm and labor forces was strengthened.

William Calvin Oates

In 1894, Jones endorsed William C. Oates’s gubernatorial candidacy, upholding the Bourbon faction of his party. After leaving office, Jones continued to mix power politics with paternalism. As governor, he had opposed calling a constitutional convention; but after the 1892 and 1894 elections he changed his mind and began campaigning for a new document. As a delegate to the 1901 convention, he supported the concept of suffrage restrictions, yet in an eloquent speech he opposed the “grandfather clause.” This was an electoral device by which men whose grandfathers had served in the military were allowed to escape requirements that otherwise would have prevented them from registering. Since the measure applied, in practical terms, only to white men, Jones denounced it as an openly discriminatory and therefore unconstitutional tool of disfranchisement.

William Calvin Oates

In 1894, Jones endorsed William C. Oates’s gubernatorial candidacy, upholding the Bourbon faction of his party. After leaving office, Jones continued to mix power politics with paternalism. As governor, he had opposed calling a constitutional convention; but after the 1892 and 1894 elections he changed his mind and began campaigning for a new document. As a delegate to the 1901 convention, he supported the concept of suffrage restrictions, yet in an eloquent speech he opposed the “grandfather clause.” This was an electoral device by which men whose grandfathers had served in the military were allowed to escape requirements that otherwise would have prevented them from registering. Since the measure applied, in practical terms, only to white men, Jones denounced it as an openly discriminatory and therefore unconstitutional tool of disfranchisement.

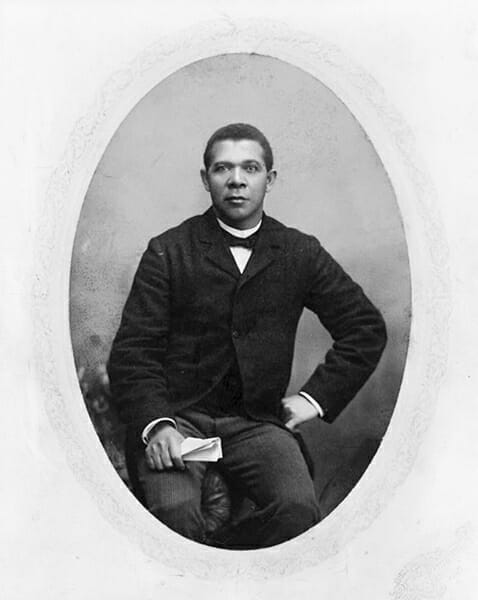

Booker T. Washington, ca. 1885

Over the years, Jones had developed a warm relationship with Booker T. Washington, president of Tuskegee Institute and renowned spokesman for African Americans. The two men were both intelligent conservatives, willing to work within the social and economic realities of their times. Although both were politically influential, each man considered himself above the worst aspects of political life. As a result of his Tuskegee connection, Jones was appointed in 1901 by Pres. Theodore Roosevelt as a federal judge for Alabama’s northern and middle districts. Beginning in 1903, Jones presided over a series of trials brought by the U.S. government against local officials, landlords, and employers whose corrupt arrangements held many black laborers and poor whites in peonage, or debt slavery. Although Jones found the actions of the defendants outrageous (as he made clear both in his published opinions and statements from the bench), he meted out mild punishments, convinced that the threat of exposure and future prosecution would serve as a deterrent.

Booker T. Washington, ca. 1885

Over the years, Jones had developed a warm relationship with Booker T. Washington, president of Tuskegee Institute and renowned spokesman for African Americans. The two men were both intelligent conservatives, willing to work within the social and economic realities of their times. Although both were politically influential, each man considered himself above the worst aspects of political life. As a result of his Tuskegee connection, Jones was appointed in 1901 by Pres. Theodore Roosevelt as a federal judge for Alabama’s northern and middle districts. Beginning in 1903, Jones presided over a series of trials brought by the U.S. government against local officials, landlords, and employers whose corrupt arrangements held many black laborers and poor whites in peonage, or debt slavery. Although Jones found the actions of the defendants outrageous (as he made clear both in his published opinions and statements from the bench), he meted out mild punishments, convinced that the threat of exposure and future prosecution would serve as a deterrent.

He may have had second thoughts, however, for between 1908 and 1911, he helped Washington and Alabama Circuit Judge William H. Thomas prepare a successful challenge to the state’s contract labor law of 1903. This law was designed to criminalize simple breaches of contract by tenant farmers, thus giving large landowners more power and control. Jones and his allies carried the fight all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where with the Alonzo Bailey decision of 1911 they succeeded in overturning the act.

Louisville & Nashville Railroad Yard, Mobile

Jones’s last act of public service embroiled him in a ratemaking controversy between the railroads and the state of Alabama. Railroads in Alabama, especially Jones’s former client the L&N, had long exercised a tremendous influence over state legislators. Railroad lobbyists had used this power to prevent the state from regulating freight rates—a situation resented for decades by farm organizations and more recently by a coalition of business and manufacturing interests led by textile manufacturer Braxton Bragg Comer. Elected governor in 1906 on a platform of railroad regulation (and backed by a rarely seen reformist majority of legislators), Comer went right to work. In turn, the railroads sued the state, claiming that the new rates were discriminatory. The cases ended up in Jones’s courtroom, pitting his loyalties to the state against his loyalties to his former employer.

Louisville & Nashville Railroad Yard, Mobile

Jones’s last act of public service embroiled him in a ratemaking controversy between the railroads and the state of Alabama. Railroads in Alabama, especially Jones’s former client the L&N, had long exercised a tremendous influence over state legislators. Railroad lobbyists had used this power to prevent the state from regulating freight rates—a situation resented for decades by farm organizations and more recently by a coalition of business and manufacturing interests led by textile manufacturer Braxton Bragg Comer. Elected governor in 1906 on a platform of railroad regulation (and backed by a rarely seen reformist majority of legislators), Comer went right to work. In turn, the railroads sued the state, claiming that the new rates were discriminatory. The cases ended up in Jones’s courtroom, pitting his loyalties to the state against his loyalties to his former employer.

Walter B. Jones

In the event, Jones considered himself to be completely objective. He freely granted injunctions that prevented the state from enforcing the new railroad laws. As a result, he was the object of a great deal of anger, both from the Comer administration and from the public. In fairness to Jones, it should be noted that the case law (in other words, the legal precedents) were complex and were weighted heavily toward the rights and privileges of railroads. Reflecting these complications, the Alabama case dragged on until the two sides compromised in February 1914. Throughout, Jones withstood popular resentment, defending the fairness and appropriateness of his actions to the last. Jones died in Montgomery, his long-time residence, two months after the settlement of the case, on April 28, 1914, survived by his wife and several children. His son Walter Burgwyn Jones was a long-time state circuit judge in Montgomery.

Walter B. Jones

In the event, Jones considered himself to be completely objective. He freely granted injunctions that prevented the state from enforcing the new railroad laws. As a result, he was the object of a great deal of anger, both from the Comer administration and from the public. In fairness to Jones, it should be noted that the case law (in other words, the legal precedents) were complex and were weighted heavily toward the rights and privileges of railroads. Reflecting these complications, the Alabama case dragged on until the two sides compromised in February 1914. Throughout, Jones withstood popular resentment, defending the fairness and appropriateness of his actions to the last. Jones died in Montgomery, his long-time residence, two months after the settlement of the case, on April 28, 1914, survived by his wife and several children. His son Walter Burgwyn Jones was a long-time state circuit judge in Montgomery.

Further Reading

- Andrews, Carol Rice, Paul M. Pruitt, Jr., and David I. Duram, eds. Gilded Age Legal Ethics: Essays on Thomas Goode Jones’ 1887 Code. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama School of Law, 2003.

- Aucoin, Brent Jude. Thomas Goode Jones: Race, Politics & Social Justice in the New South. Tuscaloosa, Al.: University of Alabama Press, 2016.

- Huggins, Carolyn Ruth. “Bourbonism and Radicalism in Alabama: The Gubernatorial Administration of Thomas Goode Jones, 1890–1894.” Master’s thesis, Auburn University, 1968.