Hugh McVay (1837)

In the summer of 1837, Hugh McVay (1766-1851) began his brief career as governor by a one-vote stroke of political fortune. As president of the state Senate before the office of lieutenant governor was created, McVay succeeded Gov. Clement Comer Clay, who resigned the office to serve Alabama in the U.S. Senate. The gubernatorial election of 1837 had already been held, and Arthur P. Bagby of Monroe County had been elected. Thus McVay served only three months until Bagby took office in November.

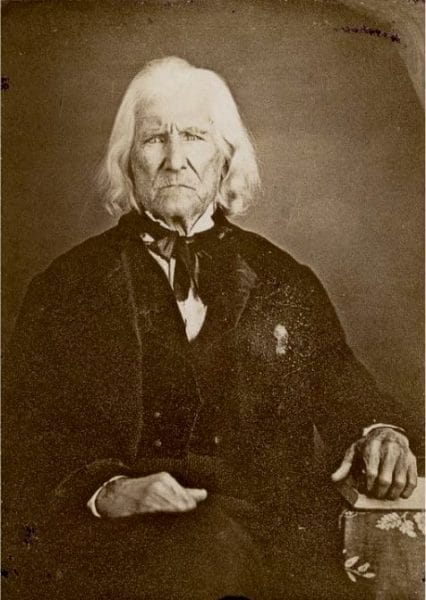

Hugh McVay

Hugh McVay was born near Greenville, South Carolina, in 1766 to Hugh and Sarah Street McVay. In the 1780s, he married Polly Hawks, with whom he had nine children. The family lived in Kentucky and Tennessee before moving to Alabama in 1807, where they became some of Madison County’s earliest squatters. McVay bought land, became a surveyor, and was one of the first attorneys admitted to the Madison County bar, although he apparently never developed a law practice.

Hugh McVay

Hugh McVay was born near Greenville, South Carolina, in 1766 to Hugh and Sarah Street McVay. In the 1780s, he married Polly Hawks, with whom he had nine children. The family lived in Kentucky and Tennessee before moving to Alabama in 1807, where they became some of Madison County’s earliest squatters. McVay bought land, became a surveyor, and was one of the first attorneys admitted to the Madison County bar, although he apparently never developed a law practice.

Polly McVay died in 1817, and soon after this, McVay moved his family to Lauderdale County and settled near Florence. In 1827, he married Sophia W. Davison in Memphis, a marriage that did not last. Sophia ran away with a man she claimed was her cousin while her husband was at the state capitol in Tuscaloosa. McVay then obtained one of the few divorces ever granted by the state legislature. This domestic rift had no known adverse consequences for the future governor.

McVay maintained a strong, long-term interest in state politics. He represented Madison County in both the Mississippi and Alabama territorial legislatures and was the Lauderdale County delegate to the 1819 constitutional convention in Huntsville. Beginning in 1820, he represented Lauderdale County in the state legislature, serving five years in the House of Representatives and 17 years in the state Senate. Because McVay was an early supporter of Pres. Andrew Jackson, the local aristocracy often opposed him, but ordinary farmers regularly supported him.

In 1836, he became president of the Senate by only a one-vote margin. Most officials, especially those in the state legislature, understood that the interim governor was only a temporary custodian of the office and would wield little power. Nearly all of the surviving correspondence of his governorship refers to him either as “acting” governor or ex officio governor or does not address him by name at all. The office of lieutenant governor would not be created until the constitutional convention of 1867. It was then abolished by the constitutional convention of 1875 and restored by the 1901 Constitutional Convention.

McVay took office while the economic depression known as the Panic of 1837 continued to wreak havoc in Alabama, especially on its overextended and badly administered state bank. McVay, a fearless Jacksonian Democrat known as a strong opponent of the banking system in Alabama, generally favored a hands-off, laissez-faire approach to the economy. Distrustful legislators who benefited from their support of the bank decided that secrecy and noncooperation were the wisest strategies to use with this governor. They deliberately kept documents related to the bank’s financial dealings from him. As he prepared to leave office, McVay admitted to the legislature and to the public that he had no information on how the banks were operating. He did not even know if any of the bonds issued to provide capital for the bank had sold at all and blamed the banks for the depression’s impact in Alabama. On November 22, 1837, the interim governor left office.

In 1840, McVay returned to the Alabama Senate and again was elected its president. During this period, he frequently played the maverick’s role. He was the only member of his party to vote against the controversial General Ticket Bill, which called for congressmen to be elected statewide rather than by districts in an attempt by Democrats to diminish Whig strength. McVay cast the only opposition vote to a Senate bill that provided for flogging anyone who embezzled from a bank, and he was the only senator from the Tennessee Valley to vote against establishing a state bank branch in that area. McVay remained in the Senate until 1844, when he returned to his home in Lauderdale County.

In an age of flamboyant oratory, McVay’s speeches were infrequent, generally short, and to the point. A contemporary described them as “plain, frank, and honest.” His plain speech matched his appearance and simple style of dress. Although his lack of formal education produced numerous unfavorable comments, he was actually a shrewd, tough man who voted independently and worried little about his popularity. By the time he retired, McVay was a wealthy plantation owner with more than 1,000 acres and 40 enslaved workers. He died on May 9, 1851, and was buried in the family cemetery outside of Florence.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Bjurberg, Richard, II. “A Political and Economic Study of Alabama’s Governors and Congressmen, 1831-1861.” Master’s thesis, Auburn University, 1947.

- Brantley, William H. Banking in Alabama, 1816-1860. 2 vols. Birmingham: Birmingham Printing Co., 1961.

- McVay, Hugh. Administrative files. Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery.