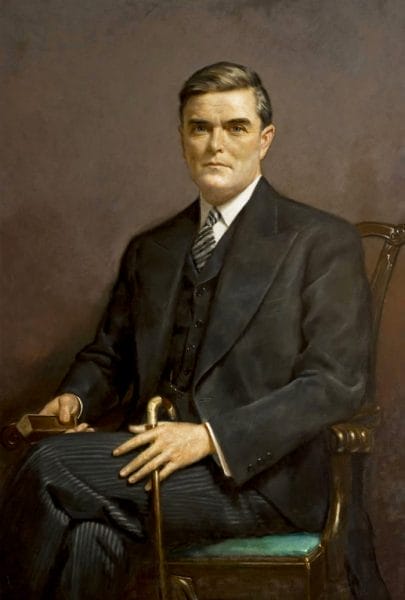

Frank M. Dixon (1939-43)

Frank M. Dixon

Frank M. Dixon (1892-1965) provided executive leadership for the state of Alabama during the early watershed years of World War II, when the state began to recover from the Great Depression. A handsome man and skilled orator, Dixon allied himself early and often with the “Black Belt-Big Mule” coalition, a group of Birmingham entrepreneurs and Black Belt planters that controlled state politics during much of the early twentieth century. As governor, Dixon is remembered for making important changes to streamline the state bureaucracy and later as a key figure in forming the Dixiecrat Party in 1948 to oppose the Democrats’ civil rights platform.

Frank M. Dixon

Frank M. Dixon (1892-1965) provided executive leadership for the state of Alabama during the early watershed years of World War II, when the state began to recover from the Great Depression. A handsome man and skilled orator, Dixon allied himself early and often with the “Black Belt-Big Mule” coalition, a group of Birmingham entrepreneurs and Black Belt planters that controlled state politics during much of the early twentieth century. As governor, Dixon is remembered for making important changes to streamline the state bureaucracy and later as a key figure in forming the Dixiecrat Party in 1948 to oppose the Democrats’ civil rights platform.

Frank Murray Dixon was born on July 25, 1892, in Oakland, California, to Frank Dixon, a preacher, and Laura Dixon. Dixon’s father was one of a long line of poor farmers from the North Carolina piedmont region who made a career from the Baptist pulpit and occasional lecturing. Dixon’s uncle was Thomas Dixon, a lawyer, preacher, state legislator, and best-selling author of several novels, including The Clansman (1905), which was later the basis for The Birth of a Nation, the first silent film to treat a serious subject. Although born in California, Frank Dixon spent most of his youth in the Tidewater region of Virginia. He received his early education in the public schools of Virginia and Washington, D.C., and graduated from the prestigious Phillips Exeter Preparatory School in New Hampshire and then Columbia University in New York City. Dixon earned a law degree from the University of Virginia in Charlottesville in 1916 and soon thereafter married Juliet Perry of Greene County, Alabama, with whom he had a son and a daughter.

Upon graduation from law school, he accepted employment with the prestigious Birmingham law firm of Frank S. White and successfully managed White’s run for the U.S. Senate. At the outbreak of World War I, Dixon resigned from the firm and volunteered with the Royal Canadian Air Corps. He was commissioned a second lieutenant and assigned to the French escadrilles as an aerial observer and machine gunner. In July 1918, the enemy shot down Dixon’s plane over Soissons, France, and he was seriously wounded, requiring doctors to amputate his right leg. The French government awarded him the Croix de Guerre with palm, made him a chevalier of the French Foreign Legion, and promoted him to major. During the 1920s, Dixon helped organize the American Legion in Alabama and served as its state commander and twice as Birmingham’s chapter post commander, service that earned him the loyalty of veterans across the state.

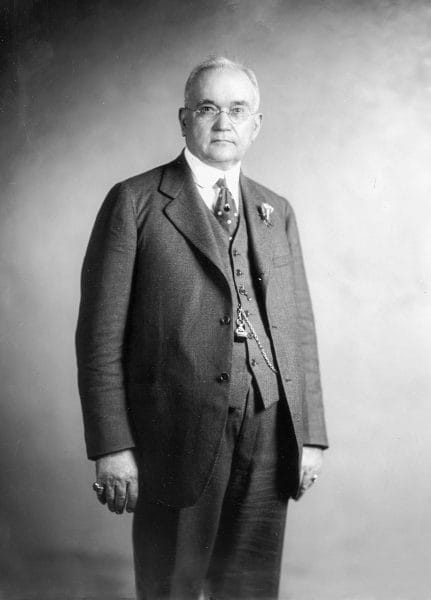

Alfred E. Smith

When he returned to Birmingham, Dixon formed his own law partnership, Bowers and Dixon, and became a successful corporate lawyer. He served as assistant solicitor of Jefferson County from 1919 to 1923 and wrote a legal treatise titled “The Local Laws of Birmingham.” He became more involved in politics during the 1920s, taking an active role in winning Alabama’s electoral votes for the controversial 1928 Democratic candidate for president, New York governor Al Smith. Like so many other Democratic loyalists in this event, Dixon warned that “bolting” the party to vote for Republican Herbert Hoover would threaten white supremacy and in effect reconstitute Reconstruction.

Alfred E. Smith

When he returned to Birmingham, Dixon formed his own law partnership, Bowers and Dixon, and became a successful corporate lawyer. He served as assistant solicitor of Jefferson County from 1919 to 1923 and wrote a legal treatise titled “The Local Laws of Birmingham.” He became more involved in politics during the 1920s, taking an active role in winning Alabama’s electoral votes for the controversial 1928 Democratic candidate for president, New York governor Al Smith. Like so many other Democratic loyalists in this event, Dixon warned that “bolting” the party to vote for Republican Herbert Hoover would threaten white supremacy and in effect reconstitute Reconstruction.

Although Dixon was an open advocate of white supremacy, he and other Birmingham executives joined plantation owners in the state in opposing the 1920s’ version of the Ku Klux Klan as a political force. The Klan represented a populist challenge to the hegemony of the Birmingham industrialists and their allies in the Black Belt. Along with the terror and intolerance of many Klansmen, the organization allied itself with the aspirations of union supporters and other working-class Alabamians.

Benjamin M. Miller

In 1934, Dixon attempted to succeed the conservative Benjamin Meek Miller as governor. Despite solid support from the planter-industrialist coalition and charges of Klan affiliation against his opponent, Dixon lost the primary election to former governor Bibb Graves. Four years later, in a process that repeated itself regularly during this era, Dixon profited from the constitutional mandate that forbade a governor from succeeding himself in office and easily defeated Chauncey Sparks to become governor. Ironically, Dixon attracted union leaders, younger voters, and other progressive Alabamians by pledging to push for reapportionment of the legislature, abolish the poll tax, and reorganize state government.

Benjamin M. Miller

In 1934, Dixon attempted to succeed the conservative Benjamin Meek Miller as governor. Despite solid support from the planter-industrialist coalition and charges of Klan affiliation against his opponent, Dixon lost the primary election to former governor Bibb Graves. Four years later, in a process that repeated itself regularly during this era, Dixon profited from the constitutional mandate that forbade a governor from succeeding himself in office and easily defeated Chauncey Sparks to become governor. Ironically, Dixon attracted union leaders, younger voters, and other progressive Alabamians by pledging to push for reapportionment of the legislature, abolish the poll tax, and reorganize state government.

Dixon’s success as governor was not accidental; he prepared for his term as few others have. In the months between his election and his inauguration, Dixon met with departing governor Graves, travelled to Washington, D.C., to secure the advice of public administration experts and even Pres. Franklin Roosevelt on his plans for changes in state government, and skillfully courted the press in Alabama. To secure legislative support for his programs, he held closed-door, pre-session conferences with groups of 20 lawmakers at a time to hear their views on his plans for administrative reform. He also placed his supporters in key leadership posts in both the state House and Senate.

Dixon launched a program to streamline Alabama’s government, basing his actions on a successful program implemented in Virginia and the advice of University of Alabama political scientist Roscoe C. Martin, an expert in the field of administrative and civil service reform. In his effort to rid the state of waste, inefficiency, duplication, and excess, Dixon eliminated 27 state agencies, largely by consolidating related and overlapping duties within one department. For example, the Department of Finance oversaw fiscal affairs by assuming the full duties of four agencies and the partial duties of six others. A new Department of Corrections replaced two older agencies; a single Department of Industrial Relations replaced six agencies, including Bibb Graves’ Department of Labor; the Conservation Department subsumed the functions of five agencies; and the Commerce Department took over those of three more.

Agencies under the leadership of committees were placed under a single individual accountable to the governor, thus centralizing power in the office of the governor. Dixon terminated all state employees who were added to state payrolls after May 3, 1938, the date he was nominated for governor, as well as every employee who had no specific and clearly assigned duties. In significant milestones for public school teachers, he helped push through a teachers’ retirement system and a teacher tenure law. Dixon’s most visible accomplishment was the establishment of a state civil service system requiring merit-based hiring of state employees. He was the first, and the last, twentieth-century governor to make an effort to eliminate duplication, inefficiency, and waste in the state’s bureaucracy.

Furthermore, Dixon reformed the way in which property taxes were assessed throughout the state. He and others in the “good government” reform movement objected to the county appointment of property tax review boards, whose members, they maintained, deliberately kept assessments at low levels and thus provided inadequate support for school districts and municipal services. Dixon’s reform bill mandated local boards be replaced by three-person boards appointed by the governor from a pool of names submitted by the county commission, the county board of education, and representatives of the county’s largest municipality. Although this measure passed, a second bill calling for state funds to be tied to a county’s willingness to increase its assessments was later withdrawn.

Liberty Ship USS Fort Laramie at ADDSCO

In 1939, as World War II began in Europe, prosperity began to slowly return to the nation and state. By 1942, more than one-half of the voluntary enlistments into the military for the entire country came from the South, putting formerly unemployed citizens to work. The governor oversaw a wartime reorganization of the Alabama State Docks at Mobile, resulting in a 400-percent increase in barge traffic. The war also brought a boom in the shipbuilding and ship repair industry to the Gulf Coast and the establishment of a major supply and repair post at the U.S. Army’s Brookley Field. Alabama enjoyed tremendous economic benefits from the industrial and military buildup associated with the war, and military bases and industries brought full employment to the state and greatly expanded the middle class.

Liberty Ship USS Fort Laramie at ADDSCO

In 1939, as World War II began in Europe, prosperity began to slowly return to the nation and state. By 1942, more than one-half of the voluntary enlistments into the military for the entire country came from the South, putting formerly unemployed citizens to work. The governor oversaw a wartime reorganization of the Alabama State Docks at Mobile, resulting in a 400-percent increase in barge traffic. The war also brought a boom in the shipbuilding and ship repair industry to the Gulf Coast and the establishment of a major supply and repair post at the U.S. Army’s Brookley Field. Alabama enjoyed tremendous economic benefits from the industrial and military buildup associated with the war, and military bases and industries brought full employment to the state and greatly expanded the middle class.

For all his achievements, Dixon was said to be “cold and inaccessible” in his style, conservative in his appointments, and given his pro-business stance, was fiercely anti-New Deal. The governor openly opposed Franklin Roosevelt’s third and fourth presidential campaigns and made opposition to Roosevelt’s 1942 Fair Employment Practices Committee and other pro-labor New Deal measures a notable feature of his administration. Dixon was a member of “Christian Americans,” thought by progressives to be a semi-fascist, anti-labor KKK group. Beyond his antilabor stance, Dixon also joined newspaper editor Grover Hall and others in Alabama to oppose a federal anti-lynching bill that called for steep fines and jail terms for policemen who lost their prisoners to mobs, additional fines against counties that hosted lynchings, and long sentences for county officials who conspired in such actions. The governor opposed it as “dangerous, unwarranted, and unwise.” When Fort Deposit whites lynched a black man for arguing with his white employer in early 1942, Dixon turned a blind eye and warned that the Klan might ride again if the federal government did not allow southern states a free hand in controlling their black populations.

1948 Democratic National Convention

The labor demands of the war era may have muted Dixon’s fundamental racism, but his postwar role as one of the primary architects of the 1948 “Dixiecrat” revolt fully revealed his bigotry. Although Dixon declined to serve as the presidential candidate for the Dixiecrats, he delivered the keynote address at its national convention in Birmingham. The Dixiecrat or States’ Rights Party organized in response to the civil rights package in the Democratic Party platform of 1948, which recommended four pieces of legislation: abolition of the poll tax, a federal antilynching law, desegregation, and a permanent Fair Employment Practices Commission. Pres. Harry S. Truman fully supported these goals, which promised the greatest federal intrusion into the South since Reconstruction, a frightening thought for those who shared Dixon’s leanings. The party eventually polled more than a million votes and carried five states in the 1948 general election. Some scholars have suggested that Dixon and his confederates were attempting to restore the South to its former place of influence within the Democratic Party, a place lost after the 1936 repeal of the rule requiring that Democratic presidential and vice presidential nominees receive two-thirds of the delegate votes at the Democratic National Convention. These high-minded ends may have played into the actions of the governor and his associates, but their overarching goal was to guarantee and maintain the racial status quo in the South.

1948 Democratic National Convention

The labor demands of the war era may have muted Dixon’s fundamental racism, but his postwar role as one of the primary architects of the 1948 “Dixiecrat” revolt fully revealed his bigotry. Although Dixon declined to serve as the presidential candidate for the Dixiecrats, he delivered the keynote address at its national convention in Birmingham. The Dixiecrat or States’ Rights Party organized in response to the civil rights package in the Democratic Party platform of 1948, which recommended four pieces of legislation: abolition of the poll tax, a federal antilynching law, desegregation, and a permanent Fair Employment Practices Commission. Pres. Harry S. Truman fully supported these goals, which promised the greatest federal intrusion into the South since Reconstruction, a frightening thought for those who shared Dixon’s leanings. The party eventually polled more than a million votes and carried five states in the 1948 general election. Some scholars have suggested that Dixon and his confederates were attempting to restore the South to its former place of influence within the Democratic Party, a place lost after the 1936 repeal of the rule requiring that Democratic presidential and vice presidential nominees receive two-thirds of the delegate votes at the Democratic National Convention. These high-minded ends may have played into the actions of the governor and his associates, but their overarching goal was to guarantee and maintain the racial status quo in the South.

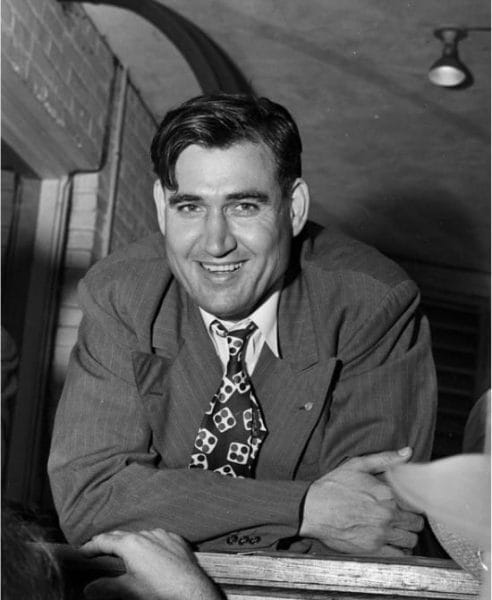

James “Big Jim” Folsom Sr.

During the 1950s and early 1960s, the former governor returned to the practice of corporate law and served as a lobbyist for conservative causes in the state legislature. In particular, he devoted much of his time to fighting labor’s attempts to overturn the state’s “right-to-work” law (a measure that forbade making union membership a condition for employment) that was passed during Gov. Gordon Persons‘s administration. The former governor also spoke against the economic and sometimes racial liberalism of Gov. James E. “Big Jim” Folsom Sr.

James “Big Jim” Folsom Sr.

During the 1950s and early 1960s, the former governor returned to the practice of corporate law and served as a lobbyist for conservative causes in the state legislature. In particular, he devoted much of his time to fighting labor’s attempts to overturn the state’s “right-to-work” law (a measure that forbade making union membership a condition for employment) that was passed during Gov. Gordon Persons‘s administration. The former governor also spoke against the economic and sometimes racial liberalism of Gov. James E. “Big Jim” Folsom Sr.

Dixon died in Birmingham on October 11, 1965, and was buried at Oak Hill Cemetery. Many of the reforms he instituted as governor are among the most significant in the state’s history. Nonetheless, in an era when Alabama’s congressional delegation was among the nation’s most liberal, Dixon may be remembered primarily as an archconservative who opposed the New Deal, turned his back on organized labor, and expressed a more virulent form of racism than many of the leading Alabama politicians of the era.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Feldman, Glenn. From Demagogue to Dixiecrat: Horace Wilkinson and the Politics of Race. Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1995.

- Permaloff, Anne, and Carl Grafton. Political Power in Alabama: The More Things Change. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995.

- The Public Life of Frank M. Dixon: Sketches and Speeches. Montgomery: Alabama Department of Archives and History, Historical and Patriotic Series, no. 18, 1979.