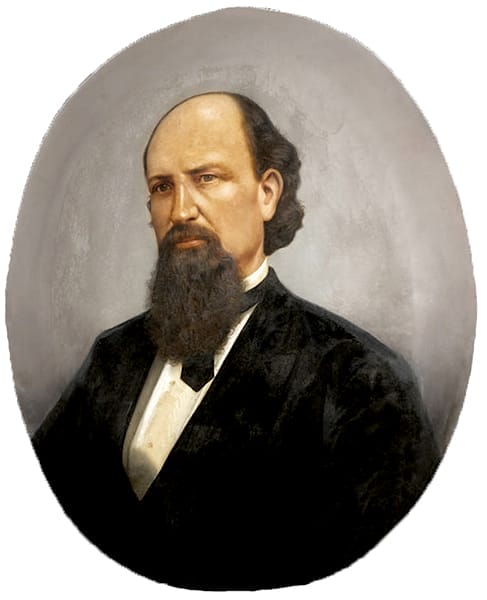

Robert Burns Lindsay (1870-72)

Robert B. Lindsay

Robert Lindsay (1824-1902) faced unprecedented difficulties as the first Democratic governor of Alabama in the aftermath of the Civil War and became nearly as unpopular as any Republican of the Reconstruction era. His administration was plagued by financial scandals and crises surrounding the state railroad and education but he also oversaw a reduction in Ku Klux Klan violence during his term in office.

Robert B. Lindsay

Robert Lindsay (1824-1902) faced unprecedented difficulties as the first Democratic governor of Alabama in the aftermath of the Civil War and became nearly as unpopular as any Republican of the Reconstruction era. His administration was plagued by financial scandals and crises surrounding the state railroad and education but he also oversaw a reduction in Ku Klux Klan violence during his term in office.

Born on July 4, 1824, in Lochmaben, Scotland, Robert Burns Lindsay was the son of John and Elizabeth McKnight Lindsay. Raised as a Presbyterian, he received an extensive education and won academic prizes at the University of St. Andrews. In 1844, Lindsay immigrated to North Carolina, where he joined his brother in the teaching profession. Five years later, he relocated to Tuscumbia, Colbert County, where he read law and was admitted to the Alabama State Bar in 1852. He was elected to represent Franklin County in the Alabama House of Representatives as a Democrat in 1853 and was elected to the state Senate in 1857. In 1854, he married Sarah Miller Winston, the half-sister of then-governor John Winston. The couple had nine children, four of whom survived into adulthood. One of those children was Maud McKnight Lindsay, who, despite her own lack of formal higher education, became a nationally known educator and author of numerous children’s books. This fortunate marriage assisted his political career, and he emerged as a prominent supporter of Winston’s campaign against railroad subsidies.

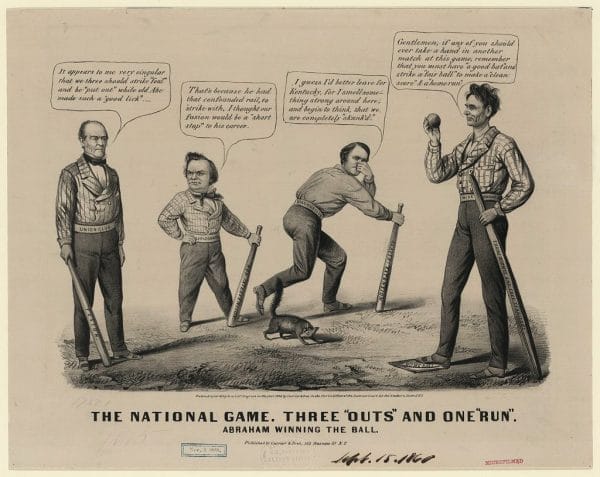

1860 Presidential Election Cartoon

In the campaign of 1860, Lindsay took a strong Unionist position, resigning a place on the John C. Breckenridge electoral ticket in order to serve on that of Stephen A. Douglas. In the crisis of 1861, he opposed immediate secession and continued to denounce it even after the Civil War began. Lindsay served for a time in Col. P. D. Roddey’s Fourth Alabama Cavalry regiment but was never an enthusiastic soldier. His tepid Confederate loyalties proved popular locally, and voters returned him to the Alabama Senate in 1865.

1860 Presidential Election Cartoon

In the campaign of 1860, Lindsay took a strong Unionist position, resigning a place on the John C. Breckenridge electoral ticket in order to serve on that of Stephen A. Douglas. In the crisis of 1861, he opposed immediate secession and continued to denounce it even after the Civil War began. Lindsay served for a time in Col. P. D. Roddey’s Fourth Alabama Cavalry regiment but was never an enthusiastic soldier. His tepid Confederate loyalties proved popular locally, and voters returned him to the Alabama Senate in 1865.

Lindsay opposed the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, but with the election of Pres. Ulysses S. Grant in 1868, he publicly called on Democrats to accept political reality. To some Alabamians, this suggested Lindsay’s potential defection to the Republican Party, but in 1870, the Democratic and Conservative Party chose Lindsay as its nominee for governor, primarily because of his moderate stance toward Reconstruction. His moderate views and lack of support for the Klan appealed to the anti-secession, white swing voters of north Alabama, many of whom might otherwise approve of Republican governor William H. Smith‘s Unionist credentials. Lindsay won the election by a narrow margin, and after several weeks of Smith disputing the result, he assumed the governorship in December 1870.

The newly elected Lindsay immediately faced a financial crisis. On January 1, 1871, the managers of Alabama’s most ambitious state-supported railroad, the Alabama & Chattanooga, proved unable to pay the interest on its bonds, claiming a short-term cash flow problem. They turned to the state to pay the interest, as called for in earlier subsidy legislation. The governor discovered, however, that his predecessor in the governor’s office had issued several hundred thousand dollars in bonds beyond those authorized by law to the Alabama & Chattanooga, which was known for corrupt practices. Lindsay pledged to honor all bona fide bonds but delayed payment because there were no records of the number of bonds issued. He sought a legislative inquiry into the matter and asked legislators to approve payments to the innocent purchasers of fraudulently issued bonds.

This plausible course of action proved disastrous. The default on the state-endorsed bonds sent a shock wave through Wall Street. The Alabama & Chattanooga managers found themselves without funds to continue operation. Worse still, the default imperiled several other half-finished railroad projects statewide. The legislature debated for months over the issue of which bonds to acknowledge, hoping to pay only those people who had unknowingly purchased unauthorized securities. The resulting delay raised speculation about the state’s ability to redeem the other securities it had endorsed. By the time the legislature gave Lindsay the latitude to decide which bonds should be paid, all Alabama railroad securities, endorsed by either the state or local governments, were devalued. Several railroad companies halted construction and ultimately went bankrupt during the Panic of 1873, an event that ultimately left the state unable to pay its other obligations as well.

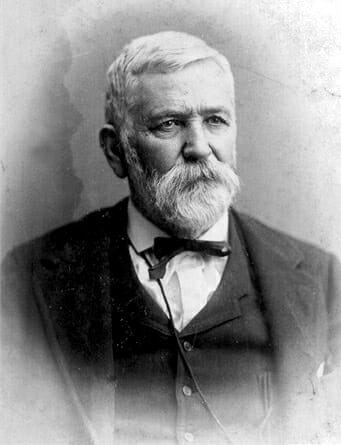

William Hugh Smith

Lindsay’s effort to distance himself from railroad corruption while attempting to protect the state’s credit satisfied no one. His revelation of Smith’s misdeeds undermined Alabama’s whole railroad program. When Lindsay seized control of the defaulting Alabama & Chattanooga, as required under the aid law, his woes were compounded. The state lacked the legal authority and expertise to finish construction, and the railroad ran at a ruinous loss and could not be sold until completed. The seizure also subjected the state to litigation, which further complicated the situation. At one point, railroad workers commandeered the bankrupt line to force payment of back wages. The most embarrassing development, however, was Lindsay’s implication in bribery. The directors of the Alabama & Chattanooga paid hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash and securities to one of Lindsay’s friends, Nathaniel McKay, who promised the directors that they would retain control of the railroad. This attempted bribe, in which Lindsay’s personal role is unclear, left the governor’s reputation in shreds.

William Hugh Smith

Lindsay’s effort to distance himself from railroad corruption while attempting to protect the state’s credit satisfied no one. His revelation of Smith’s misdeeds undermined Alabama’s whole railroad program. When Lindsay seized control of the defaulting Alabama & Chattanooga, as required under the aid law, his woes were compounded. The state lacked the legal authority and expertise to finish construction, and the railroad ran at a ruinous loss and could not be sold until completed. The seizure also subjected the state to litigation, which further complicated the situation. At one point, railroad workers commandeered the bankrupt line to force payment of back wages. The most embarrassing development, however, was Lindsay’s implication in bribery. The directors of the Alabama & Chattanooga paid hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash and securities to one of Lindsay’s friends, Nathaniel McKay, who promised the directors that they would retain control of the railroad. This attempted bribe, in which Lindsay’s personal role is unclear, left the governor’s reputation in shreds.

In other areas, however, Lindsay was able to claim some accomplishments, perhaps most importantly, a decline in Ku Klux Klan activity. The statewide Democratic victory eliminated some of the partisan reasons for terrorism. Enhanced national scrutiny of the Klan and the threat of federal intervention against it may also explain the decrease in Klan violence. Lindsay’s policy toward the Klan was complex: he often tried to stop violence in Klan-ridden localities by encouraging beleaguered Republican local officials to resign, whereupon he then appointed Democrats who were more acceptable to the white population. Thus, Lindsay was less committed to the rule of law than he was to the elimination of the Republican Party in Alabama. Still, he publicly denounced vigilantism, and such avowals may have contributed to the decline in Klan activity.

Robert B. Lindsay

Some Democratic constituents applauded Lindsay’s spending restraint, but cuts in education funding that closed schools prematurely undermined the governor’s support. These problems resulted from the fiscal difficulties created by the railroad scandals. Within the Democratic Party, Lindsay had antagonized railroad interests on the one hand and those who favored the wholesale repudiation of the railroad bonds, on the other. His most vocal critic was Robert McKee, of the Selma Argus, who editorialized that Lindsay diverted school money to “Wall Street gamblers and foreign speculators.” At the 1872 Democratic state convention, Lindsay’s announcement that he would not be a candidate reportedly evoked applause, and only the chairman’s timely intervention prevented hisses at his name. The Democratic gubernatorial candidate, ex-secessionist Thomas H. Herndon of Mobile, ran poorly. His opponent, David P. Lewis, won by a substantial margin, with eight previously Democratic north Alabama counties voting Republican. Lindsay thus had dispirited his party and paved the way for a Republican resurgence, ironically abetted by the decline of terrorist violence that once supported Democrat candidates.

Robert B. Lindsay

Some Democratic constituents applauded Lindsay’s spending restraint, but cuts in education funding that closed schools prematurely undermined the governor’s support. These problems resulted from the fiscal difficulties created by the railroad scandals. Within the Democratic Party, Lindsay had antagonized railroad interests on the one hand and those who favored the wholesale repudiation of the railroad bonds, on the other. His most vocal critic was Robert McKee, of the Selma Argus, who editorialized that Lindsay diverted school money to “Wall Street gamblers and foreign speculators.” At the 1872 Democratic state convention, Lindsay’s announcement that he would not be a candidate reportedly evoked applause, and only the chairman’s timely intervention prevented hisses at his name. The Democratic gubernatorial candidate, ex-secessionist Thomas H. Herndon of Mobile, ran poorly. His opponent, David P. Lewis, won by a substantial margin, with eight previously Democratic north Alabama counties voting Republican. Lindsay thus had dispirited his party and paved the way for a Republican resurgence, ironically abetted by the decline of terrorist violence that once supported Democrat candidates.

Two months after leaving office, Lindsay was stricken with paralysis. He returned to his law practice at a limited level but ignored politics beyond occasional defenses of his administration in the press. He remained an invalid until his death in Tuscumbia on February 13, 1902. As governor, Lindsay was faced with difficult fiscal challenges for which no attractive solution existed. His response to the crisis exacerbated the situation, with ruinous result to his party and the state as well.

Further Reading

- Summers, Mark W. Railroads, Reconstruction, and the Gospel of Prosperity: Aid under the Radical Republicans, 1865-1877. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1984.