Historically Black Colleges and Universities in Alabama

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) in Alabama and other states were established after the Civil War to provide educational opportunities to thousands of newly freed slaves and later to skirt segregation policies prior to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The schools established in Alabama under this premise were: Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical University (AAMU), Alabama State University, Concordia College, Miles College, Oakwood University, Selma University, Stillman College, Talladega College, and Tuskegee University.

Winsborough Hall at Stillman College

During the period of slavery, Blacks in the United States were prohibited from education and learning. But even at this time, enslaved people thirsted for knowledge and viewed education as the key to their freedom. In Alabama, enslaved people pursued various forms of education despite laws barring them from learning to read and write. These stealth efforts included underground reading rooms in which educated slaves taught each other to read, learning from the slave owners’ wives, who were occasionally sympathetic toward the children of slaves, and being taught by abolitionists.

Winsborough Hall at Stillman College

During the period of slavery, Blacks in the United States were prohibited from education and learning. But even at this time, enslaved people thirsted for knowledge and viewed education as the key to their freedom. In Alabama, enslaved people pursued various forms of education despite laws barring them from learning to read and write. These stealth efforts included underground reading rooms in which educated slaves taught each other to read, learning from the slave owners’ wives, who were occasionally sympathetic toward the children of slaves, and being taught by abolitionists.

After the Civil War, the daunting task of educating more than four million formerly enslaved people, with nearly 440,000 in Alabama alone, was shouldered by the federal Freedman’s Bureau and many northern church missionaries. In 1865, the Freedmen’s Bureau began establishing black colleges in Alabama and elsewhere in the South, employing staff and teachers with primarily military backgrounds. Most black colleges were institutions of higher learning in name only during the first decades of their existence, however. These facilities generally provided primary and secondary education, a feature that was true of most early white colleges.

Booker T. Washington Monument

Alabama’s private black colleges—Miles College, Oakwood College, Selma University, Stillman College, Talladega College, Concordia College (now closed), and Tuskegee University—were founded by black and white churches and missionary societies actively working with the Freedmen’s Bureau. Some of the more prominent black churches involved were the African Methodist Episcopal and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion, whereas the most important white organizations were the American Baptist Home Mission Society and the American Missionary Association. But there were others as well. The benevolence of these latter organizations was often tinged with self-interest and occasionally racism. Their goals in establishing these colleges were to convert the formerly enslaved people to their brand of Christianity and to rid the country of the “menace” of uneducated African Americans.

Booker T. Washington Monument

Alabama’s private black colleges—Miles College, Oakwood College, Selma University, Stillman College, Talladega College, Concordia College (now closed), and Tuskegee University—were founded by black and white churches and missionary societies actively working with the Freedmen’s Bureau. Some of the more prominent black churches involved were the African Methodist Episcopal and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion, whereas the most important white organizations were the American Baptist Home Mission Society and the American Missionary Association. But there were others as well. The benevolence of these latter organizations was often tinged with self-interest and occasionally racism. Their goals in establishing these colleges were to convert the formerly enslaved people to their brand of Christianity and to rid the country of the “menace” of uneducated African Americans.

Black education in Alabama received a boost in 1890, when the federal government promoted public black colleges under the second Morrill Act. Whereas the Morrill Act of 1862 had provided federal lands with which to fund and locate schools, the 1890 act stipulated that states practicing segregation in their public colleges and universities would forfeit federal funding unless they established agricultural and mechanical institutions for the black population. Although the wording of the Morrill Act called for the equitable division of federal funds, these new black institutions received less funding than their white counterparts and thus had inferior facilities. Alabama A&M University and the Tuskegee Institute were among the institutions supported by these federal funds.

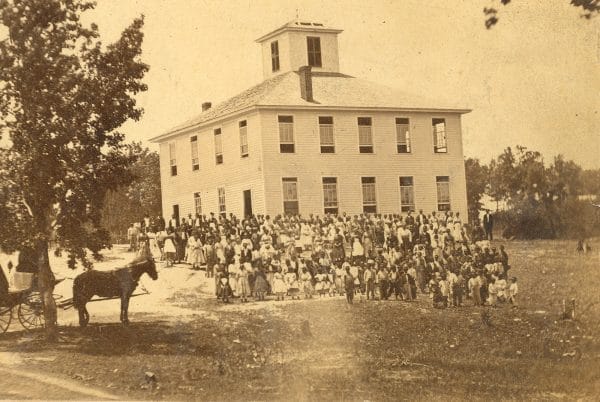

Lincoln Normal School

Alabama State University was the first black college in the state, established as the Lincoln School in Perry County by nine former slaves as a private institution in 1867. One year later, the Alabama Board of Education designated the school a state teaching institution, allotting it some state funding. After several name changes, the school moved to Montgomery in 1887. It was designated Alabama State University in 1969. Located in a hub of desegregation and civil rights activities, the institution played a leading role in negotiating racial strife in the 1950s and 1960s. Today, Alabama State University enrolls more than 5,000 students and boasts 47 degree programs.

Lincoln Normal School

Alabama State University was the first black college in the state, established as the Lincoln School in Perry County by nine former slaves as a private institution in 1867. One year later, the Alabama Board of Education designated the school a state teaching institution, allotting it some state funding. After several name changes, the school moved to Montgomery in 1887. It was designated Alabama State University in 1969. Located in a hub of desegregation and civil rights activities, the institution played a leading role in negotiating racial strife in the 1950s and 1960s. Today, Alabama State University enrolls more than 5,000 students and boasts 47 degree programs.

Talladega College

In 1869, two freedmen, William Savery and Thomas Tarrant, established Talladega College, the state’s oldest private black college. It had its roots in the Swayne School, established just two years earlier by the same men and named for Wager T. Swayne, assistant commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau. Interestingly, some of the first pupils at Talladega College were white and their classroom buildings were built by former slaves. The institution is affiliated with the United Church of Christ and currently boasts 1,500 students. Of note, the institution has a solid track record for placing its alumni in graduate and professional programs throughout the country.

Talladega College

In 1869, two freedmen, William Savery and Thomas Tarrant, established Talladega College, the state’s oldest private black college. It had its roots in the Swayne School, established just two years earlier by the same men and named for Wager T. Swayne, assistant commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau. Interestingly, some of the first pupils at Talladega College were white and their classroom buildings were built by former slaves. The institution is affiliated with the United Church of Christ and currently boasts 1,500 students. Of note, the institution has a solid track record for placing its alumni in graduate and professional programs throughout the country.

Alabama A&M University

Alabama’s other public black college, Huntsville-based Alabama A&M, was established in 1875 as the Huntsville Normal School dedicated to instructing teachers. With the support of the 1890 Morrill Act came a new location and a name change; the institution moved to Normal, Madison County, and was known as the State Agricultural and Mechanical College for Negroes. Alabama A&M was granted university status by the state in 1969. Currently, the institution serves more than 5,000 students and continues its commitment to the agricultural and mechanical arts as well as offering a liberal arts curriculum to its students.

Alabama A&M University

Alabama’s other public black college, Huntsville-based Alabama A&M, was established in 1875 as the Huntsville Normal School dedicated to instructing teachers. With the support of the 1890 Morrill Act came a new location and a name change; the institution moved to Normal, Madison County, and was known as the State Agricultural and Mechanical College for Negroes. Alabama A&M was granted university status by the state in 1969. Currently, the institution serves more than 5,000 students and continues its commitment to the agricultural and mechanical arts as well as offering a liberal arts curriculum to its students.

Selma University

Selma University, established by the Alabama State Missionary Baptist Convention in 1878 as the Alabama Baptist Normal and Theological School, was focused on training teachers, although it educated ministers as well. The institution had an African American president beginning in 1881, a rarity as most black colleges were led by whites in the early decades. Like Alabama State, Selma University also played a key role in the civil rights movement, with many of its students and faculty participating in the famous march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge led by Martin Luther King Jr. Renamed Selma University in 1980, the institution currently enrolls approximately 600 students, most of whom are from Alabama, with a focus on the liberal arts.

Selma University

Selma University, established by the Alabama State Missionary Baptist Convention in 1878 as the Alabama Baptist Normal and Theological School, was focused on training teachers, although it educated ministers as well. The institution had an African American president beginning in 1881, a rarity as most black colleges were led by whites in the early decades. Like Alabama State, Selma University also played a key role in the civil rights movement, with many of its students and faculty participating in the famous march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge led by Martin Luther King Jr. Renamed Selma University in 1980, the institution currently enrolls approximately 600 students, most of whom are from Alabama, with a focus on the liberal arts.

Tuskegee University, located in Tuskegee, Macon County, is the most well-known black college in Alabama and was founded in 1881 by educator Booker T. Washington. Space for the college was first provided by the Butler Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, but eventually the institution moved to an abandoned plantation, where it has remained to the present. Tuskegee was renowned for its dedication to the industrial arts and now enrolls approximately 3,000 students in its strong liberal arts curriculum as well as degree programs in many professional fields.

Oakwood University

Oakwood University, located in Huntsville on what used to be a plantation, was established in 1896 by the Seventh-Day Adventist Church with which the institution maintains close affiliation. During its early years, the college was known as the Oakwood Manual Training School and its curriculum focused on industrial education. In 1944, however, Oakwood adopted a more liberal-arts-oriented focus and began to offer bachelor’s degrees and was renamed Oakwood College. It was renamed Oakwood University in 2007 and currently enrolls more than 1,800 students.

Oakwood University

Oakwood University, located in Huntsville on what used to be a plantation, was established in 1896 by the Seventh-Day Adventist Church with which the institution maintains close affiliation. During its early years, the college was known as the Oakwood Manual Training School and its curriculum focused on industrial education. In 1944, however, Oakwood adopted a more liberal-arts-oriented focus and began to offer bachelor’s degrees and was renamed Oakwood College. It was renamed Oakwood University in 2007 and currently enrolls more than 1,800 students.

Miles College is located in Fairfield, in Jefferson County. The institution was founded by the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church in 1905 and continues to have strong ties to that church. Throughout its history, Miles College has had a strong relationship with the surrounding community even as it promoted racial uplift for blacks. During the civil rights era president Lucius Pitts helped to negotiate race relations with white citizens in the Birmingham area and strongly supported his students’ desires to participate in nonviolent protests. With more than 1,800 students, Miles College is considered one of the most competitive black colleges in the country, boasting high graduation rates. It also has provided three consecutive alumni as mayors of Birmingham.

Concordia College of Alabama in Selma was established in 1922 as the Alabama Lutheran Academy and College through the effort of Wilcox County native Rosa Young and the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod. Minister Robert O. Lynn was the first president of the institution, placing an emphasis on the spiritual and educational welfare of African Americans. Until 1983, Concordia was designated a junior college but began offering bachelor’s degrees in 1994. After several years of declining enrollment and financial difficulties, the college graduated its last class in April 2018 and closed permanently.

Each of these HBCUs contributes to the overall education of the Alabama citizenry as well as the economic life of the state. They are each unique in their strengths, but also share a common history of supporting the uplift of African Americans and the community as a whole. Notable alumni include civil rights activist Rosa Parks (Alabama State), writer Ralph Ellison (Tuskegee), Birmingham’s first African American mayor Richard Arrington (Miles College), and singer Lionel Richie (Tuskegee).

Further Reading

- Drewy, Henry N., Humphrey Doermann, and Susan H. Anderson. Stand and Prosper: Private Black Colleges and Their Students. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- Miles College Centennial History Committee. Miles College: The First One Hundred Years. Birmingham, Ala.: Arcadia Publishing, 2005.

- Westhauser, Karl E., Elaine M. Smith, and Jennifer A. Fremlin. Creating Community: Life and Learning at Montgomery’s Black University. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 2005.