Mobile's Mardi Gras

Mardi Gras Parade on Royal Street

Mobile’s Mardi Gras celebration was the first in America and remains an important part of Alabama’s Gulf Coast culture. Mardi Gras was first observed when Mobile was a French colony, a century before the founding of Alabama. Today, thousands of Alabamians and visitors come to Mobile annually to participate in the various parades, which are sponsored by local mystic societies comprised of secret members. Presiding over the revelry are an elected king and queen, who are chosen each year from among the various societies. At the parades, spectators catch candy and trinkets thrown from elaborately decorated themed floats sponsored by the various mystic societies and take part in one of the America’s oldest cultural celebrations.

Mardi Gras Parade on Royal Street

Mobile’s Mardi Gras celebration was the first in America and remains an important part of Alabama’s Gulf Coast culture. Mardi Gras was first observed when Mobile was a French colony, a century before the founding of Alabama. Today, thousands of Alabamians and visitors come to Mobile annually to participate in the various parades, which are sponsored by local mystic societies comprised of secret members. Presiding over the revelry are an elected king and queen, who are chosen each year from among the various societies. At the parades, spectators catch candy and trinkets thrown from elaborately decorated themed floats sponsored by the various mystic societies and take part in one of the America’s oldest cultural celebrations.

Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville

Mardi Gras is a Catholic festival that traditionally begins 40 days before Easter and precedes the Lenten period. The name is French for “Fat Tuesday,” which is the last day of merriment and feasting and refers to the traditional practice of eating a fattened calf in preparation for the fasting and self-sacrifice of Lent. Mardi Gras celebrations first came to what is now Alabama with the early French explorers, who were led by Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville. He recorded the first observance of Mardi Gras in Mobile in his journal in 1699. Men in the camp marked the occasion with feasts, dancing, and a night of masked revelry. The annual celebrations of the festival continued as control of the city passed from the French to the British and the Spanish and finally to the United States in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase.

Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville

Mardi Gras is a Catholic festival that traditionally begins 40 days before Easter and precedes the Lenten period. The name is French for “Fat Tuesday,” which is the last day of merriment and feasting and refers to the traditional practice of eating a fattened calf in preparation for the fasting and self-sacrifice of Lent. Mardi Gras celebrations first came to what is now Alabama with the early French explorers, who were led by Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville. He recorded the first observance of Mardi Gras in Mobile in his journal in 1699. Men in the camp marked the occasion with feasts, dancing, and a night of masked revelry. The annual celebrations of the festival continued as control of the city passed from the French to the British and the Spanish and finally to the United States in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase.

Knights of Revelry Float

Mardi Gras activities remained an important part of social celebration in south Alabama, but the festivities were not held during the traditional pre-Lenten period. The first American celebration was held, instead, on New Year’s Eve in 1831, when a cotton broker named Michael Krafft and several of his friends held a spontaneous parade through downtown Mobile carrying rakes, cowbells, and other farming implements. When the young men’s motive behind the revelry was questioned, Krafft wryly replied that they were the Cowbellion de Rakin Society, formed to celebrate the coming year. The Cowbellion parade became an annual affair with costumes, masks, and, by 1840, themed parades. By the 1850s, several Cowbellions had migrated to New Orleans, where they continued their traditions.

Knights of Revelry Float

Mardi Gras activities remained an important part of social celebration in south Alabama, but the festivities were not held during the traditional pre-Lenten period. The first American celebration was held, instead, on New Year’s Eve in 1831, when a cotton broker named Michael Krafft and several of his friends held a spontaneous parade through downtown Mobile carrying rakes, cowbells, and other farming implements. When the young men’s motive behind the revelry was questioned, Krafft wryly replied that they were the Cowbellion de Rakin Society, formed to celebrate the coming year. The Cowbellion parade became an annual affair with costumes, masks, and, by 1840, themed parades. By the 1850s, several Cowbellions had migrated to New Orleans, where they continued their traditions.

The Cowbellion Society was the first of what would be many such organizations, which became known as mystic societies because their membership was secret. It was made up of Mobile’s upper-class young men, who refused to allow the city’s numerous dockworkers and nonprofessional men into their ranks. Women also were excluded. Working-class Mobilians soon formed their own societies, however. In 1841, cotton warehouse workers founded the Strikers Independent Society, named for the act of striking, or marking, cotton bales for shipping.

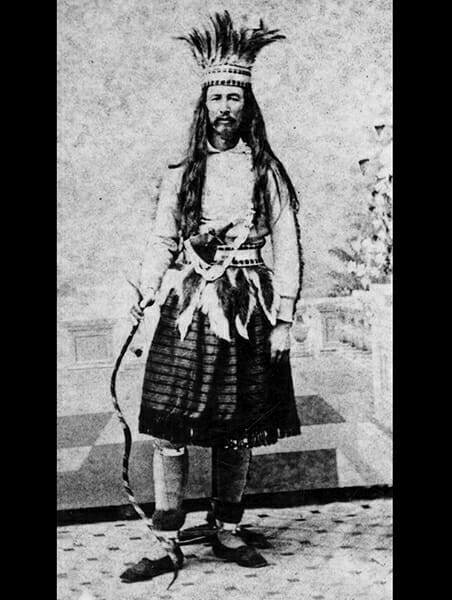

Joe Cain

The Civil War brought a halt to such celebratory activities, and in April 1865, Union troops took control of the city. Mobile’s Mardi Gras festivities resumed unexpectedly the following year when Joseph Stillwell Cain, a local clerk and former member of the Tea Drinkers Mystic Society, led a parade through the occupied city dressed as a fictional Indian named Chief Slackabamarinico. Cain exuberantly declared an end to Mobile’s suffering and signaled the return of the city’s parading activities, to the delight of local residents. He also succeeded in moving Mobile’s celebration from New Year’s Eve to the traditional Fat Tuesday. Older societies such as the Cowbellions and the Striker’s continued to hold their parades on New Year’s Eve, but soon Mobile’s carnival season revolved around Fat Tuesday.

Joe Cain

The Civil War brought a halt to such celebratory activities, and in April 1865, Union troops took control of the city. Mobile’s Mardi Gras festivities resumed unexpectedly the following year when Joseph Stillwell Cain, a local clerk and former member of the Tea Drinkers Mystic Society, led a parade through the occupied city dressed as a fictional Indian named Chief Slackabamarinico. Cain exuberantly declared an end to Mobile’s suffering and signaled the return of the city’s parading activities, to the delight of local residents. He also succeeded in moving Mobile’s celebration from New Year’s Eve to the traditional Fat Tuesday. Older societies such as the Cowbellions and the Striker’s continued to hold their parades on New Year’s Eve, but soon Mobile’s carnival season revolved around Fat Tuesday.

During and after Reconstruction, Mardi Gras became the premier event of the city’s social elite and a way of celebrating the Lost Cause. New societies representing different portions of the city’s diverse population began to appear. The Order of Myths (OOM), established in 1867, chose as its emblem Folly chasing Death around a broken column, imagery that was seen by many as a symbol of the “Lost Cause.” At the end of the traditional OOM parade, Death is defeated, and Folly wins the day. In 1870, a group of young men between the ages of 18 and 21 formed the Infant Mystics, probably because they were too young to join other societies. The Knights of Revelry (KOR), formed in 1874. Their emblem of Folly dancing in a champagne glass between two crescent moons remains a familiar site during Mardi Gras parades

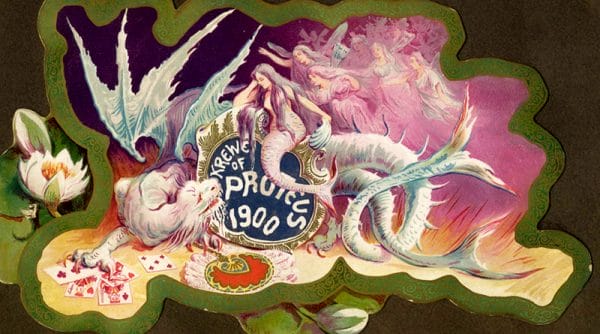

Mardi Gras Party Invitation 1900

By the 1870s, the Carnival season in Mobile had become much more elaborate than earlier celebrations. Mobile’s mystic societies sponsored expensive private balls after their parades. During these events, members participated in elaborate themed plays, called tableaux, which were usually similar in theme to the society’s parade theme. The various mystic societies remained isolated during these activities. In 1871, a group of businessmen and city boosters formed the Mobile Carnival Association to organize and structure the various events and serve as a link among the various societies. This was the first attempt to coordinate the public activities of the individual societies. The association also introduced the practice of choosing a Mardi Gras emperor, named King Felix, for each season.

Mardi Gras Party Invitation 1900

By the 1870s, the Carnival season in Mobile had become much more elaborate than earlier celebrations. Mobile’s mystic societies sponsored expensive private balls after their parades. During these events, members participated in elaborate themed plays, called tableaux, which were usually similar in theme to the society’s parade theme. The various mystic societies remained isolated during these activities. In 1871, a group of businessmen and city boosters formed the Mobile Carnival Association to organize and structure the various events and serve as a link among the various societies. This was the first attempt to coordinate the public activities of the individual societies. The association also introduced the practice of choosing a Mardi Gras emperor, named King Felix, for each season.

Knights of Revelry Float, 1895

The association brought about an increase in Mardi Gras activity, and by 1880 the event had grown even larger. In 1884, a group of Jewish men, headed by clerk Dave Levi, formed the Comic Cowboys. They had been banned from other societies because of anti-Semitism and thus organized each year’s parade as a satirical look at current events. Behind the motto “Without Malice,” the Comic Cowboys poked fun at local customs, politicians, and other mystic societies. Beginning in 1917, the Comic Cowboys Queen, known as “Little Eva,” was portrayed as a large, transvestite woman.

Knights of Revelry Float, 1895

The association brought about an increase in Mardi Gras activity, and by 1880 the event had grown even larger. In 1884, a group of Jewish men, headed by clerk Dave Levi, formed the Comic Cowboys. They had been banned from other societies because of anti-Semitism and thus organized each year’s parade as a satirical look at current events. Behind the motto “Without Malice,” the Comic Cowboys poked fun at local customs, politicians, and other mystic societies. Beginning in 1917, the Comic Cowboys Queen, known as “Little Eva,” was portrayed as a large, transvestite woman.

Despite the increase in the number of societies and participants in Mobile’s Mardi Gras, festivities remained largely spectator events. Mystic societies were closed to working-class and most minority citizens, as well as women. Even the KOR and the Comic Cowboys maintained strict qualifications for membership. It was not until 1890 that the first women’s society, the MWM, was organized and held its first ball. The first female parading society, the Polka Dots, was not founded until 1949.

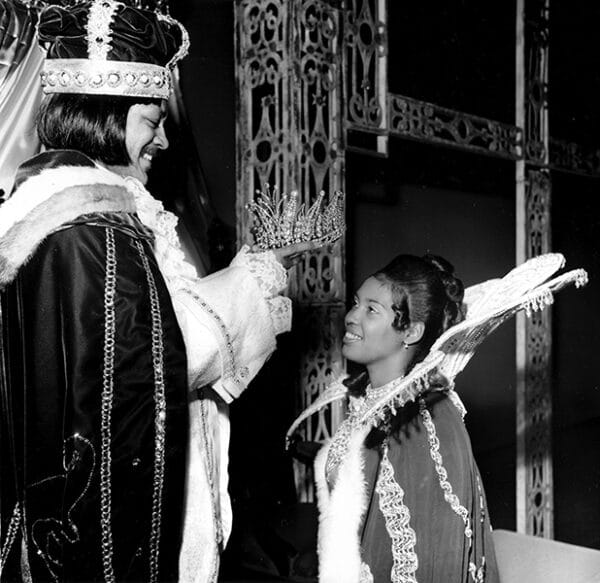

Mardi Gras King and Queen

Mobile’s African American community had played an important but secondary role in parading societies for several decades, beginning in the 1890s. Before this time, African Americans walked alongside the horse-drawn floats and did not participate in society events. African Americans watched the various parades but had no mystic societies or Carnival balls of their own until the Order of Doves was established in 1894. The Doves held their first ball in the Gilmer Rifles Armory and continued to host balls until 1914. The first African American parading society, the Knights of May Zulu, organized by float-builder A. S. May in 1938, paraded along Mobile’s Davis Avenue until 1952. By 1940, more and more African American societies had formed and begun parading, and the groups founded the Colored Carnival Association (CCA) to coordinate the activities of the societies and schedule parades. The CCA, renamed the Mobile Area Mardi Gras Association (MAMGA) in the 1970s, set up a voting system that allowed members to elect a “mayor” to serve as grand marshal of their parades. The African American celebration has its own king, named Elixis. The first king of Mobile’s African American Mardi Gras was Mobile politician Alex Herman. His daughter, former U.S. secretary of labor Alexis Herman, served as queen in 1974.

Mardi Gras King and Queen

Mobile’s African American community had played an important but secondary role in parading societies for several decades, beginning in the 1890s. Before this time, African Americans walked alongside the horse-drawn floats and did not participate in society events. African Americans watched the various parades but had no mystic societies or Carnival balls of their own until the Order of Doves was established in 1894. The Doves held their first ball in the Gilmer Rifles Armory and continued to host balls until 1914. The first African American parading society, the Knights of May Zulu, organized by float-builder A. S. May in 1938, paraded along Mobile’s Davis Avenue until 1952. By 1940, more and more African American societies had formed and begun parading, and the groups founded the Colored Carnival Association (CCA) to coordinate the activities of the societies and schedule parades. The CCA, renamed the Mobile Area Mardi Gras Association (MAMGA) in the 1970s, set up a voting system that allowed members to elect a “mayor” to serve as grand marshal of their parades. The African American celebration has its own king, named Elixis. The first king of Mobile’s African American Mardi Gras was Mobile politician Alex Herman. His daughter, former U.S. secretary of labor Alexis Herman, served as queen in 1974.

Despite inroads by minority groups, the vast majority of working-class revelers were still only spectators to the annual celebrations. In the 1930s, there was a public masquerade ball at the city wharf on Dauphin Street. But pressure from various mystic societies put a quick end to the popular event, which they felt conflicted with their own traditions and activities. Society members perceived that public Carnival balls diminished the prestige that came with membership in the secretive and highly selective mystic societies. Only two other such balls occurred in 1949 and 1952. In 1962, the recently-formed Le Krewe de Bienville hosted an open ball for Mobile citizens and tourists.

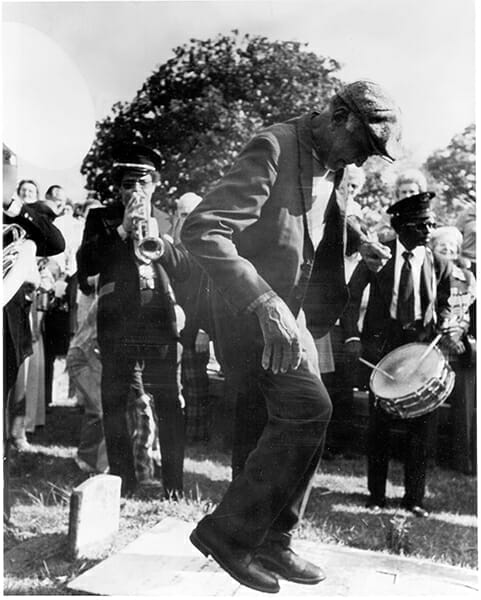

Excelsior Band at Joe Cain’s Grave, 1967

The campaign to make Mobile’s Mardi Gras more inclusive achieved its greatest success, however, when local author Julian Lee Rayford set out to honor Joe Cain for reviving Mardi Gras in Mobile. Rayford’s first act commemorating the savior of Mobile’s Mardi Gras tradition was to transport Cain’s body from a cemetery in Bayou La Batre to the Church Street Graveyard in downtown Mobile. Cain was interred with all the pomp and revelry of a Mardi Gras parade, with a jazz-band procession and throngs of mourners. The burial and commemoration of Cain was so popular that Rayford and others decided to make it an annual event, held the Sunday before Fat Tuesday. They instituted the Joe Cain Day Parade (also known as The People’s Parade) to the Church Street Graveyard, led by a person dressed as Chief Slackabamirinico, and it quickly became one of the most popular Mardi Gras events. Thousands of spectators gather in the old graveyard, listen to Mobile’s Excelsior Band, and marvel as Cain is memorialized by Mobilians dancing atop his grave. When the ceremony begins in the graveyard, several veiled women dressed in mourning

Excelsior Band at Joe Cain’s Grave, 1967

The campaign to make Mobile’s Mardi Gras more inclusive achieved its greatest success, however, when local author Julian Lee Rayford set out to honor Joe Cain for reviving Mardi Gras in Mobile. Rayford’s first act commemorating the savior of Mobile’s Mardi Gras tradition was to transport Cain’s body from a cemetery in Bayou La Batre to the Church Street Graveyard in downtown Mobile. Cain was interred with all the pomp and revelry of a Mardi Gras parade, with a jazz-band procession and throngs of mourners. The burial and commemoration of Cain was so popular that Rayford and others decided to make it an annual event, held the Sunday before Fat Tuesday. They instituted the Joe Cain Day Parade (also known as The People’s Parade) to the Church Street Graveyard, led by a person dressed as Chief Slackabamirinico, and it quickly became one of the most popular Mardi Gras events. Thousands of spectators gather in the old graveyard, listen to Mobile’s Excelsior Band, and marvel as Cain is memorialized by Mobilians dancing atop his grave. When the ceremony begins in the graveyard, several veiled women dressed in mourning

Cain’s Merry Widows

robes, know as Cain’s Merry Widows, cry aloud and lament his loss to the world. Joe Cain Day remains one of the most popular events of Mobile’s Mardi Gras celebration, and its public parade is seen by many Mobilians as a response to the stiffness of the traditional mystic societies.

Cain’s Merry Widows

robes, know as Cain’s Merry Widows, cry aloud and lament his loss to the world. Joe Cain Day remains one of the most popular events of Mobile’s Mardi Gras celebration, and its public parade is seen by many Mobilians as a response to the stiffness of the traditional mystic societies.

Mardi Gras means various things to different segments of Mobile’s population. Some see the associated events as a tremendous boost to the city’s economy. Others see the annual merriment as a constant economic and moral drain on the city. Each year, Mobile’s Carnival activities grow in size and cost. What began as a one-day celebration before Lent has evolved into weeks of carefully scripted events, culminating with the day-long parade of mystic societies through the downtown streets on Fat Tuesday. But the mystic societies remain largely separated by race.

Mardi Gras Marching Band

In 2003, the Conde Explorers became the first and only racially mixed parading society in Mobile. The founding of the Conde Explorers also reflects an important contrast between Carnival in Mobile and New Orleans, where several of the oldest mystic societies voted to stop parading rather than comply with local ordinances requiring their complete integration. Tensions are less openly expressed during Mobile’s festivities, possibly because they are not as severe and possibly because of the tradition of sponsoring parades and balls for predominantly African American communities in the city, begun by MAMGA. Despite all of this, Carnival in Mobile remains, in Julian Lee Rayford’s words, the city’s “civic safety-valve.” Thousands of Mobilians and tourists fill downtown parade routes and await incoming treats. The multi-colored beads thrown in other cities are considered skimpy fare in Mobile, where floats are piled high with toys, candy, and Mobile’s signature treat: the Moonpie.

Mardi Gras Marching Band

In 2003, the Conde Explorers became the first and only racially mixed parading society in Mobile. The founding of the Conde Explorers also reflects an important contrast between Carnival in Mobile and New Orleans, where several of the oldest mystic societies voted to stop parading rather than comply with local ordinances requiring their complete integration. Tensions are less openly expressed during Mobile’s festivities, possibly because they are not as severe and possibly because of the tradition of sponsoring parades and balls for predominantly African American communities in the city, begun by MAMGA. Despite all of this, Carnival in Mobile remains, in Julian Lee Rayford’s words, the city’s “civic safety-valve.” Thousands of Mobilians and tourists fill downtown parade routes and await incoming treats. The multi-colored beads thrown in other cities are considered skimpy fare in Mobile, where floats are piled high with toys, candy, and Mobile’s signature treat: the Moonpie.

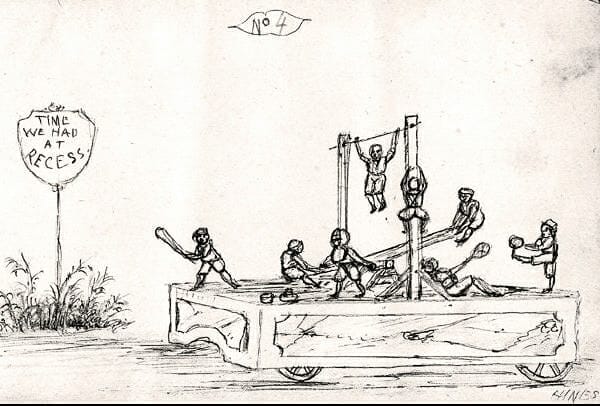

Mardi Gras Float Drawing

Mardi Gras remains an integral part of the cultural celebration of French tradition along the Gulf Coast. The William and Emily Hearin Mobile Carnival Museum celebrates that heritage with numerous exhibits related to the city’s Mardi Gras history. Smaller cities in Mobile and Baldwin counties have recently begun holding their own parades, ensuring that the Mardi Gras tradition in South Alabama will continue into the future.

Mardi Gras Float Drawing

Mardi Gras remains an integral part of the cultural celebration of French tradition along the Gulf Coast. The William and Emily Hearin Mobile Carnival Museum celebrates that heritage with numerous exhibits related to the city’s Mardi Gras history. Smaller cities in Mobile and Baldwin counties have recently begun holding their own parades, ensuring that the Mardi Gras tradition in South Alabama will continue into the future.

Additional Resources

Kinser, Samuel. Carnival, American Style: Mardi Gras at Mobile and New Orleans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

“Mardi Gras in Mobile: Excerpts from the 1908 Diary of Young Visitor, Senta Jones.” Gulf Coast Historical Review 11 (Spring 1996): 69-76.

Mardi Gras Vertical Files, Mobile Public Library Local History and Genealogy Section, Mobile, Alabama.

S. Blake McNeely Photographic Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Mobile, Alabama.