Adele "Vera" Hall

Adele “Vera” Hall (1902-1964) is considered by many music fans to be the foremost singer of the blues and African American spirituals to come out of depression-era Alabama. Vera Hall, as she is popularly known, recorded a large body of work for ethnomusicologists (individuals who study music in a cultural context) working for the Library of Congress with the help of Alabama folklorist Ruby Pickens Tartt. Hall’s music is widely available and continues to influence contemporary artists, such as Moby, and attract new audiences.

Adele “Vera” Hall

Ward was born around the turn of the century in Payneville, just outside of Livingston in Sumter County, to Agnes and Efron “Zully” Hall. Her father worked on a local farm in Sumter and rented land from Will Cobb. She had two older sisters, Bessie and Estelle, and a younger brother who died in infancy. In a 1948 interview with Alan Lomax, Hall recalled her mother as the disciplinarian of the family. She learned some of her first songs from her parents. In the same interview, Hall noted that her mother’s favorite song was “I’ve Got a Home in the Rock,” and her father’s favorite song was “When I’m Standing Wondering, Lord, Show Me the Way.” Of her mother, Hall said, Agnes sang all the time, especially while cooking or washing. Although scholars have found no records that document whether Hall received any formal education, they do know that she could read and write.

Adele “Vera” Hall

Ward was born around the turn of the century in Payneville, just outside of Livingston in Sumter County, to Agnes and Efron “Zully” Hall. Her father worked on a local farm in Sumter and rented land from Will Cobb. She had two older sisters, Bessie and Estelle, and a younger brother who died in infancy. In a 1948 interview with Alan Lomax, Hall recalled her mother as the disciplinarian of the family. She learned some of her first songs from her parents. In the same interview, Hall noted that her mother’s favorite song was “I’ve Got a Home in the Rock,” and her father’s favorite song was “When I’m Standing Wondering, Lord, Show Me the Way.” Of her mother, Hall said, Agnes sang all the time, especially while cooking or washing. Although scholars have found no records that document whether Hall received any formal education, they do know that she could read and write.

During her childhood and again in the 1930s, Hall attended Old Shiloh Baptist Church, near Payneville, where she became well known in the community for her singing. Along with the early influence of her parents, Hall learned much from Rich Amerson, another Sumter County folksinger and storyteller who gained national exposure through the recordings made by ethnomusicologists John Lomax and Harold Courlander. Amerson taught Hall an unusual collection of songs, including both blues and folk songs.

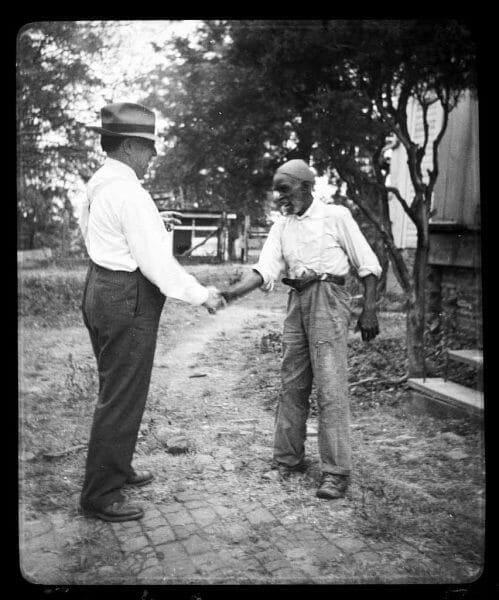

John Lomax Sr. and Richard Brown

Hall’s family, though poor, appeared to be better off than others in their community. Hall’s father Ephron owned both a horse and wagon, and the family farm fed them with a variety of vegetables and livestock. Hall noted that if her mother needed money she would sell eggs or vegetables to help with other needs that the family had. At the age of 11, Hall began taking care of children for families in Livingston. While traveling with one family in Tuscaloosa, Hall met Nels Riddle of Tuscaloosa, around 1917. Hall was almost 16 at the time of the marriage.

John Lomax Sr. and Richard Brown

Hall’s family, though poor, appeared to be better off than others in their community. Hall’s father Ephron owned both a horse and wagon, and the family farm fed them with a variety of vegetables and livestock. Hall noted that if her mother needed money she would sell eggs or vegetables to help with other needs that the family had. At the age of 11, Hall began taking care of children for families in Livingston. While traveling with one family in Tuscaloosa, Hall met Nels Riddle of Tuscaloosa, around 1917. Hall was almost 16 at the time of the marriage.

Following their marriage in 1918, she and Nels had one daughter, Minnie Ada, in 1920. According to Hall, her husband worked in the coal mines and was fatally shot in a fight in either 1923 or 1924. Hall continued to live in Tuscaloosa working as a cook and washerwoman, but many sources conclude that Hall’s daughter returned to Sumter County to live with Hall’s mother. With the onset of the Great Depression, Hall returned to Livingston to work and live with family. Hall’s daughter died in 1940 of chronic hepatitis, and Hall cared for Minnie Ada’s sons, John Rogers and Willie Nixon Moore. During a 1940 recording trip, John Lomax reported that Hall mentioned a railroad worker, Willie Ward, of Greensboro, who wanted to marry her. Hall also noted that she, Ward, and others frequented an area of Livingston referred to as Tin Cup that was known for its juke joints for entertainment on Saturday nights. There is no record that a marriage ever took place between Ward and Hall, but many scholars speculate that it is from this relationship that Hall learned more modern blues and railroad songs.

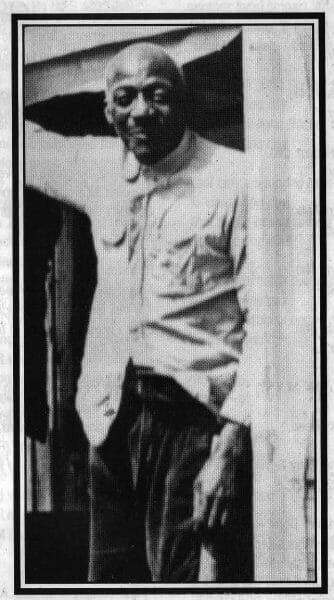

Dock Reed

Often singers made distinctions in the types of songs that they performed. For Hall, these would have fallen into the categories of play-party songs, singing games in which children provided vocal accompaniment; spirituals that were religious in nature; work songs that often accompanied occupations such as railroad songs; and blues songs, which often reflected human conflict and tragedy. These blues spoke of the singer’s experiences, and often shed light on social contexts of the period. Hall sang all types of songs. Other singers, such as her cousin, Dock Reed, sang only spirituals because he felt the other types of songs were sinful. All of these songs were passed from singer to singer orally and not through recordings or musical scores. As a result, variations of verses and performance styles occurred. For ethnomusicologists like Lomax, Hall’s ability to improvise and remember the songs that she had heard only once or twice was remarkable. Lomax praised her as having the “loveliest untrained voice [he] had ever recorded.”

Dock Reed

Often singers made distinctions in the types of songs that they performed. For Hall, these would have fallen into the categories of play-party songs, singing games in which children provided vocal accompaniment; spirituals that were religious in nature; work songs that often accompanied occupations such as railroad songs; and blues songs, which often reflected human conflict and tragedy. These blues spoke of the singer’s experiences, and often shed light on social contexts of the period. Hall sang all types of songs. Other singers, such as her cousin, Dock Reed, sang only spirituals because he felt the other types of songs were sinful. All of these songs were passed from singer to singer orally and not through recordings or musical scores. As a result, variations of verses and performance styles occurred. For ethnomusicologists like Lomax, Hall’s ability to improvise and remember the songs that she had heard only once or twice was remarkable. Lomax praised her as having the “loveliest untrained voice [he] had ever recorded.”

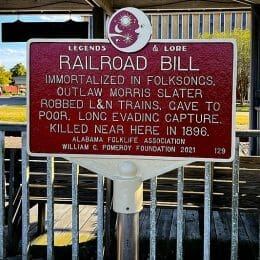

Hall was introduced to John Lomax in July of 1937, when he was traveling through the Southeast gathering music for the Works Progress Administration and the Library of Congress. Lomax and Hall met through Ruby Pickens Tartt, a folklorist and Sumter County native, who had been appointed the chairman of the WPA’s Writers’ Project for Sumter County. As a first assignment, she had been asked to document and submit eight full-length spirituals. The spirituals she sent in caught the attention of Lomax and brought him to Sumter County. In the presence of her cousin Dock Reed, Hall only sang spirituals. During that first recording trip of 1937, Hall and Reed together recorded songs such as “Mourin’ Song,” “Oh, Jesus, Jes’ Write My Name,” and “Let Me Ride” together. Lomax recorded Hall by herself singing spirituals such as “I Feel Like My Time Ain’t Long,” “I Believe, I’ll Go Back Home,” and “John Saw Dat Number.” When her cousin was not present, Hall recorded folk songs such as “Railroad Bill,” “John Henry,” “Little Sally Walker,” and “Stagolee.” In subsequent trips, Lomax would record Hall singing both spirituals and blues and folk songs including “Another Man Done Gone,” “Trouble So Hard,” “Boll Weevil Blues,” and “Wild Ox Moan.”

Ruby Pickens Tartt

After the recordings made by Lomax and Tartt became available to the public, others travelled to Sumter County to do their own recordings, and Hall was one of the most sought after singers. In the 1940s, she gained the attention of an international audience when the British Broadcasting Corporation played her recording of “Another Man Done Gone” as an example of folk music in the United States. This recording was also played during a commemoration ceremony of the Emancipation Proclamation at the Library of Congress. In 1945, Hall recorded songs for Byron Arnold, then a music professor at the University of Alabama, that were later released as a collection of folksongs edited by Joy D. Baklanoff and John Bealle. In 1948, Hall travelled with John Lomax’s son, Alan, to New York and performed at the American Music Festival at Columbia University on May 15. During the trip, Alan and his wife, Elizabeth, conducted interviews with Hall that appeared in a fictional biographical portrayal of Hall in the novel, The Rainbow Sign, published by Duell, Solan, and Pearce in 1959. In the early 1950s, Hall worked with ethnomusicologist Harold Courlander, who was making recordings for the American Folkways Collection. In the recordings, Hall again sang spirituals with her cousin, and sang secular songs when Reed was not present.

Ruby Pickens Tartt

After the recordings made by Lomax and Tartt became available to the public, others travelled to Sumter County to do their own recordings, and Hall was one of the most sought after singers. In the 1940s, she gained the attention of an international audience when the British Broadcasting Corporation played her recording of “Another Man Done Gone” as an example of folk music in the United States. This recording was also played during a commemoration ceremony of the Emancipation Proclamation at the Library of Congress. In 1945, Hall recorded songs for Byron Arnold, then a music professor at the University of Alabama, that were later released as a collection of folksongs edited by Joy D. Baklanoff and John Bealle. In 1948, Hall travelled with John Lomax’s son, Alan, to New York and performed at the American Music Festival at Columbia University on May 15. During the trip, Alan and his wife, Elizabeth, conducted interviews with Hall that appeared in a fictional biographical portrayal of Hall in the novel, The Rainbow Sign, published by Duell, Solan, and Pearce in 1959. In the early 1950s, Hall worked with ethnomusicologist Harold Courlander, who was making recordings for the American Folkways Collection. In the recordings, Hall again sang spirituals with her cousin, and sang secular songs when Reed was not present.

Little is known about Hall after the Courlander recordings and the publication of The Rainbow Sign other than that she continued to work as washerwoman and cook. In 1964, Hall died and was buried in the Livingston Cemetery near Morning Star Baptist Church. Her gravesite is now lost, after the wooden cross marking the site was bulldozed away at some time in the 1970s.

A new generation of listeners discovered Hall following the 1999 release of techno-artist Moby’s multi-platinum album Play, which incorporated Hall’s version of “Trouble So Hard.” Scholars and folksong enthusiasts continue to study the work of Hall. In her recordings, examples of early blues and versions of folk songs appear than can be found no where else. Hall’s voice and her renditions of traditional songs are a defining part of Southern Black culture and the Black Belt region. In March 2005, Hall joined Ruby Pickens Tartt in the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame. On April 21, 2007, the Sumter County Historical Society and the Alabama Blues Project unveiled a memorial to Hall adjacent to the courthouse square.

Music Recordings

Further Reading

- Arnold, Byron, ed. Folk Songs of Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1950.

- Courlander, Harold. “The Passing of a Great Singer- Vera Hall.” Sing Out: The Folk Song Magazine 14 (July 1964): 30-31.

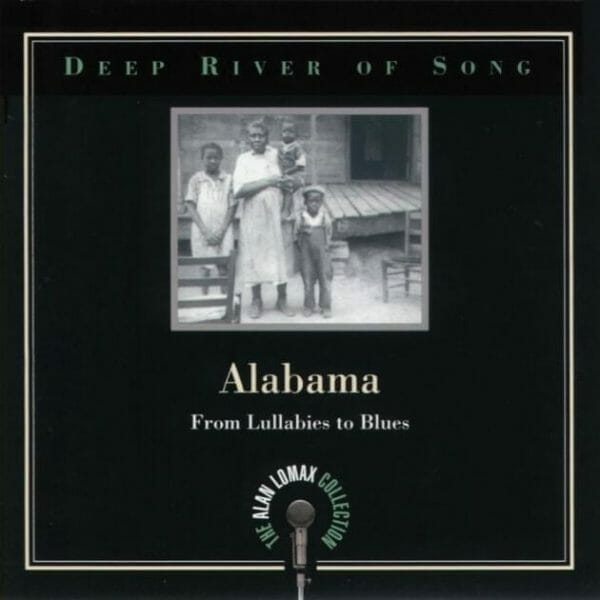

- Lomax, John A. Deep River of Song: Alabama, Various Artists. Cambridge, Mass.: Rounder Records, 2001.

- McGregory, Jerrilyn. “Livingston, Alabama Blues: The Significance of Vera Ward Hall.” Tributaries 5 (2002) 72-137.

- Solomon, Jack and Olivia Solomon, ed. Honey in the Rock: The Ruby Pickens Tartt Collection of Religious Folk Songs from Sumter County, Alabama. Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1992.