Africatown

Africatown (also spelled AfricaTown and African Town) is a small Mobile neighborhood established by many of the people who arrived on the Clotilda, the last documented slave ship to reach the United States. Co-founder Cudjo Lewis achieved notoriety when he was interviewed about his experiences in Africa, his journey to Mobile on the ship, and his life after he regained his freedom. The Africatown settlement (formerly called African Town) is located north of the city on a hill by the Alabama River in the area known as Plateau and Magazine Point.

Africatown Heritage House Ceremony

On Sunday July 8, 1860—52 years after the United States had abolished the international slave trade—the Clotilda, captained by shipbuilder William Foster, sailed into Mobile Bay with 110 African men, women, and children between the ages of 5 and 23 on board. He had selected them in a barracoon (a prison where captives were held before being sent across the Atlantic) in Ouidah, in present-day Benin. Some of the people on board the Clotilda were Yoruba traders abducted in eastern Benin; others came from the mountainous Atakora region in the west; there were also Nupe and Dendi peoples among them as well. The largest group—mostly Yoruba of the Isha sub-group—had been captured in a dawn raid led by Ghezo, the king of Dahomey, in the Banté region of Benin. After their secret arrival—in 1820 the introduction of Africans was declared an act of piracy punishable by death—about 25 young people were sold upriver to slave brokers, but the majority remained in Mobile. Thirty-two became the property of Timothy Meaher, who had financed the expedition, and his brother James enslaved eight others, including Cudjo Lewis; twenty were sent to Burns Meaher’s plantation in Clarke County; between five and eight went to William Foster as payment for the trip; and others were bought by plantation owner Thomas Buford. The young Africans were employed as deckhands, field hands, and domestics.

Africatown Heritage House Ceremony

On Sunday July 8, 1860—52 years after the United States had abolished the international slave trade—the Clotilda, captained by shipbuilder William Foster, sailed into Mobile Bay with 110 African men, women, and children between the ages of 5 and 23 on board. He had selected them in a barracoon (a prison where captives were held before being sent across the Atlantic) in Ouidah, in present-day Benin. Some of the people on board the Clotilda were Yoruba traders abducted in eastern Benin; others came from the mountainous Atakora region in the west; there were also Nupe and Dendi peoples among them as well. The largest group—mostly Yoruba of the Isha sub-group—had been captured in a dawn raid led by Ghezo, the king of Dahomey, in the Banté region of Benin. After their secret arrival—in 1820 the introduction of Africans was declared an act of piracy punishable by death—about 25 young people were sold upriver to slave brokers, but the majority remained in Mobile. Thirty-two became the property of Timothy Meaher, who had financed the expedition, and his brother James enslaved eight others, including Cudjo Lewis; twenty were sent to Burns Meaher’s plantation in Clarke County; between five and eight went to William Foster as payment for the trip; and others were bought by plantation owner Thomas Buford. The young Africans were employed as deckhands, field hands, and domestics.

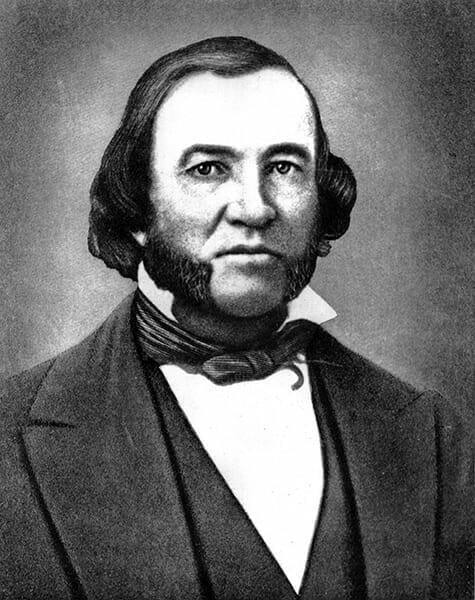

Timothy Meaher

After emancipation following the end of the Civil War in 1865, those formerly enslaved on Burns Meaher’s plantation joined the others in the area north of Mobile known as Plateau. They hoped to return to Africa and their families but were unable to do so for lack of money and thus decided to remain where they were, albeit on their own terms. In 1866, they established the settlement of African Town as the first town founded and continuously occupied and controlled by blacks in the United States. The men, who were employed in shipyards and mills, and the women, who sold vegetables in Mobile, worked hard, saved their money, and were able to buy land from their former owners and others. African Town consisted of two sections: a large one of about 50 acres and a smaller one of seven acres located two miles west of the other. The smaller section, was called Lewis Quarters after Charlie Lewis (Oluale was his Yoruba name), one of the founders of the compound. In the 1890s, African Town consisted of about 30 houses set in a clearing in a pine forest.

Timothy Meaher

After emancipation following the end of the Civil War in 1865, those formerly enslaved on Burns Meaher’s plantation joined the others in the area north of Mobile known as Plateau. They hoped to return to Africa and their families but were unable to do so for lack of money and thus decided to remain where they were, albeit on their own terms. In 1866, they established the settlement of African Town as the first town founded and continuously occupied and controlled by blacks in the United States. The men, who were employed in shipyards and mills, and the women, who sold vegetables in Mobile, worked hard, saved their money, and were able to buy land from their former owners and others. African Town consisted of two sections: a large one of about 50 acres and a smaller one of seven acres located two miles west of the other. The smaller section, was called Lewis Quarters after Charlie Lewis (Oluale was his Yoruba name), one of the founders of the compound. In the 1890s, African Town consisted of about 30 houses set in a clearing in a pine forest.

The residents appointed Gumpa, a Fon relative of King Ghezo known as Peter Lee or African Peter, as their chief. They also established a judicial system for the town based on their own laws, which were administered by two judges, Jaba Shade—well versed in herbal medicine—and Ossa Keeby. They also built the first school in the area to provide their children with better opportunities. Their school teacher was a young African American woman.

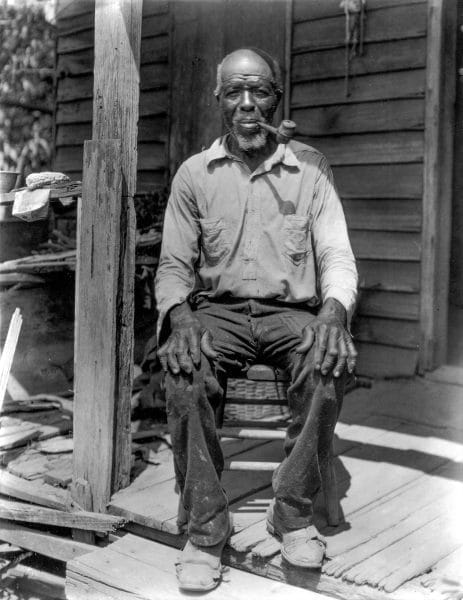

Lewis, Cudjo

Although the residents of African Town owned land, had become U.S. citizens in 1868, and enjoyed a certain degree of autonomy, they never ceased to long for their families and homelands back in Africa. They became aware of subsidized passage to the West African nation of Liberia (established by prominent U.S. political leaders and others for the purpose of creating a homeland for Free Blacks) through the American Colonization Society (founded in 1816 to send Free Blacks to Liberia) and requested passage in 1870. Their appeal was unsuccessful, however, and they remained in African Town. In 1869, the residents, who thus far had continued to practice their traditional religions, largely converted to Christianity. They built the first church in the neighborhood, Old Landmark Baptist Church, in 1872 (it was rebuilt in bricks in the early twentieth century) and opened a graveyard in 1876. Over time, several couples, including Cudjo and Abile Lewis, and Ossa and Annie Keeby, bought additional land, and the settlement expanded.

Lewis, Cudjo

Although the residents of African Town owned land, had become U.S. citizens in 1868, and enjoyed a certain degree of autonomy, they never ceased to long for their families and homelands back in Africa. They became aware of subsidized passage to the West African nation of Liberia (established by prominent U.S. political leaders and others for the purpose of creating a homeland for Free Blacks) through the American Colonization Society (founded in 1816 to send Free Blacks to Liberia) and requested passage in 1870. Their appeal was unsuccessful, however, and they remained in African Town. In 1869, the residents, who thus far had continued to practice their traditional religions, largely converted to Christianity. They built the first church in the neighborhood, Old Landmark Baptist Church, in 1872 (it was rebuilt in bricks in the early twentieth century) and opened a graveyard in 1876. Over time, several couples, including Cudjo and Abile Lewis, and Ossa and Annie Keeby, bought additional land, and the settlement expanded.

Beginning at the time when they were enslaved, some of the young Africans had intermarried with African Americans, but there had also been tensions from the first days on the plantations between the two groups. The Africans complained that some of their neighbors ridiculed and shunned them. The African shipmates were a very tight-knit community who, even in servitude, remained defiant to whomever threatened or disparaged them, whether white or black. These tensions with some Americans continued after emancipation and in part explain why the Africans felt the need to establish their own settlement, church, school, and graveyard.

By the 1880s, African Town was home to a second generation that had never been to Africa but had been told repeatedly by their parents that it was a land of abundance and beauty. Many of the youngsters had both an American and a West African name, knew the geography of their parents’ homelands, and, among those who had two African parents, also spoke their indigenous languages. Many of these second-generation residents lived into the 1950s, and thus some African Americans whose origin was in the international slave trade spoke African languages well into the twentieth century.

Africatown Cemetery

The men and women of the Clotilda lived in African Town as much on their own terms as they could, but many also played a larger role in U.S. history. Some men were forced to work for the Confederacy and some voted in the elections of 1874. One female resident, and perhaps others, belonged to the Freedman’s Bank and the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association, which led the first reparations movement by African Americans. Cudjo Lewis and Gumpa sued major railroads after suffering injuries in accidents, and Lewis’s case went all the way to the Alabama Supreme Court, and one of his sons was a victim of the infamous convict-leasing system. Several of the former shipmates were interviewed by the local, regional, and national press and spoke with celebrated figures, including Alabama native and noted author Zora Neale Hurston, Tuskegee Institute founder Booker T. Washington, and Pulitzer Prize-winner Roark Bradford. Thus despite their deliberate insularity, the Africans were directly involved, more so than many of their contemporaries, in the significant events of their times. The last survivors in Africatown died between 1912 and 1922; Cudjo Lewis, the very last, died in 1935.

Africatown Cemetery

The men and women of the Clotilda lived in African Town as much on their own terms as they could, but many also played a larger role in U.S. history. Some men were forced to work for the Confederacy and some voted in the elections of 1874. One female resident, and perhaps others, belonged to the Freedman’s Bank and the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association, which led the first reparations movement by African Americans. Cudjo Lewis and Gumpa sued major railroads after suffering injuries in accidents, and Lewis’s case went all the way to the Alabama Supreme Court, and one of his sons was a victim of the infamous convict-leasing system. Several of the former shipmates were interviewed by the local, regional, and national press and spoke with celebrated figures, including Alabama native and noted author Zora Neale Hurston, Tuskegee Institute founder Booker T. Washington, and Pulitzer Prize-winner Roark Bradford. Thus despite their deliberate insularity, the Africans were directly involved, more so than many of their contemporaries, in the significant events of their times. The last survivors in Africatown died between 1912 and 1922; Cudjo Lewis, the very last, died in 1935.

Their descendants now number in the thousands and carry with them their ancestors’ legacy of pride and distinctiveness, attachment to Africa, and sense of place through their belonging to a small town that has no equivalent in this country. The descendants of the founders of African Town are unique among African Americans in that they know who their African ancestors were, what their names were, where they came from, and for some of them, what they looked like. Some still live in the settlement that is now called Africatown. The log cabins built by their ancestors no longer exist and have been replaced by modern houses; but the trees and bushes planted by the men and women of the Clotilda are still there, as are their graves. In March 1984, nine descendants established the nonprofit Africatown Direct Descendants of the Clotilda, Inc. to preserve the heritage and story of the people kidnapped and brought to Alabama on the Clotilda. In February 2021, the group, along with Mobile civic leaders, broke ground on the site of the future Africatown Heritage House museum and welcome center.

In April 2018, reporter Ben Raines and a team of underwater archaeologists found the wreck of the Clotilda in the 12 Mile Island section of the Mobile River. The discovery was not announced until the following year so that verification could be completed. On May 22, 2019, the Alabama Historical Commission officially announced its discovery. In 2021, the wreck site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Further Reading

- Diouf, Sylviane Anna. Dreams of Africa in Alabama: The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Story of the Last Africans Brought to America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Hurston, Zora Neale. Barracoon. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2020.

- Raines, Ben. The Last Slave Ship: The True Story of How Clotilda Was Found, Her Descendants, and an Extraordinary Reckoning. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2022.

- Roche, Emma Langdon. Historic Sketches of the South. New York: Knickerbocker Press, 1914.