Streight's Raid

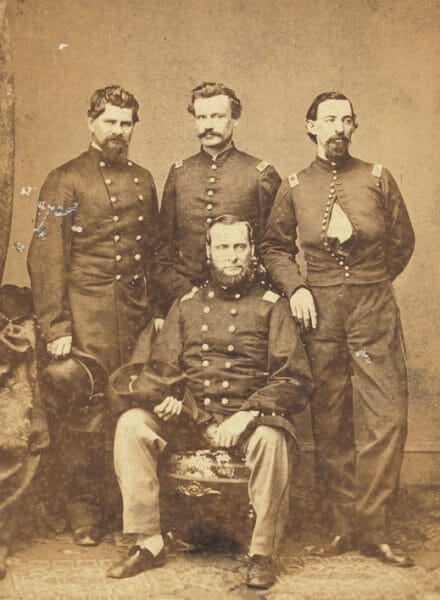

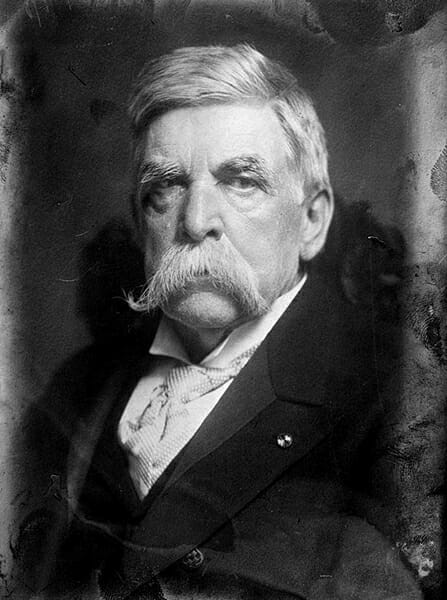

Abel D. Streight

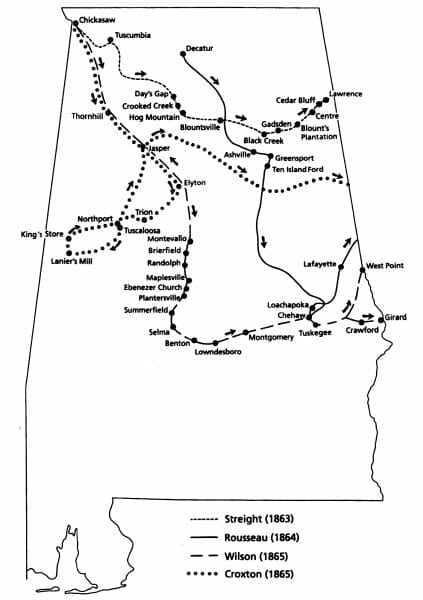

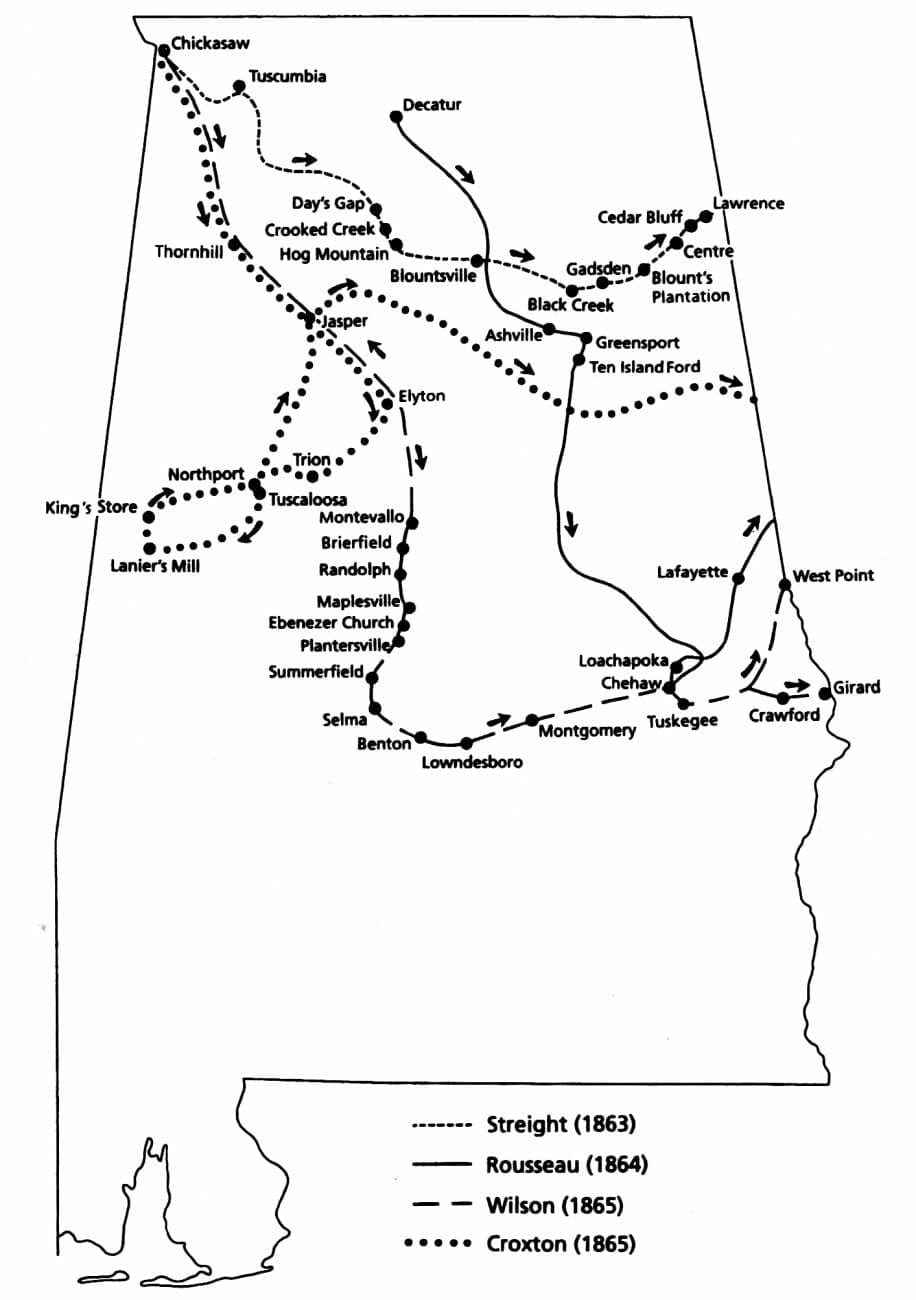

Streight’s Raid, a Civil War campaign conducted by U.S. Army colonel Abel D. Streight from April 19 to May 3, 1863, to destroy portions of the Western & Atlantic Railroad, had little effect upon federal attempts to defeat the Confederate Army of Tennessee. Its principal significance lies in the legends that grew up around Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest’s capture of Streight and his men, with the aid of Emma Sansom, near the present-day city of Gadsden.

Abel D. Streight

Streight’s Raid, a Civil War campaign conducted by U.S. Army colonel Abel D. Streight from April 19 to May 3, 1863, to destroy portions of the Western & Atlantic Railroad, had little effect upon federal attempts to defeat the Confederate Army of Tennessee. Its principal significance lies in the legends that grew up around Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest’s capture of Streight and his men, with the aid of Emma Sansom, near the present-day city of Gadsden.

Streight, a native of New York, owned a printing company and lumber yard in Indianapolis, Indiana, and was a Republican Party member who openly espoused abolitionist sympathies. He enlisted in the Federal army days after Confederates fired upon Fort Sumter. In July 1862, Streight served as part of the Federal occupation force in northern Alabama. During this brief period, he routinely interacted with north Alabama Unionists, as those who remained loyal to the United States were known, and recruited many into the federal army. He greatly overestimated their numbers, and this misconception, shared by many Federal military commanders and President Abraham Lincoln, jeopardized the planned raids by U.S. Army troops months before they began.

In March 1863, U.S. Army major general William Starke Rosecrans ordered Streight to organize a provisional brigade to conduct a mounted raid across northern Alabama and into northwest Georgia, where it would strike the Western & Atlantic Railroad, one of the Confederate Army of Tennessee’s supply arteries located in northwest Georgia. Streight’s brigade contained portions of the First West Tennessee and First Alabama (U.S.A.) cavalry regiments, and the Third Ohio, Fifty-first Indiana, Seventy-third Illinois, and the Eightieth Illinois infantry regiments, totaling approximately 1,700 soldiers. Lacking horses, a majority of Streight’s infantry instead mounted temperamental mules recently procured from farms in western Tennessee. Many of the mules were unbroken, old, or incapable of carrying their riders for great distances without frequent stops. The amused onlookers who watched the large mass of federal soldiers riding mules through the countryside embarrassed the men and slowed their movement. During the raid, Confederates hurled insults toward the brigade, referring to them as the “Jackass Cavalry.” Undoubtedly, the lack of horses had a negative effect on troop morale.

Grenville Dodge

Mules were not the only problem. The raid’s success also depended upon Brig. Gen. Grenville Dodge’s ability to screen Streight’s movements from Confederate cavalry commanded by General Forrest as well as cavalry led by Col. Phillip Roddey, both part of the Army of Tennessee. On April 19, 1863, Streight’s brigade boarded several boats at Nashville that transported the force southward on the Tennessee River and disembarked at Eastport, Mississippi. That night, a stampede scattered approximately 400 of the brigade’s mules into the surrounding countryside causing a delay as Streight waited in Eastport for a shipment of mules. Two days later, Streight rendezvoused with Dodge and his 8,000 cavalrymen, and moved toward Tuscumbia, in Colbert County. During the march, skirmishers who had detached from Forrest’s division impeded Federal movements. At Tuscumbia, Streight and Dodge separated, with Streight riding toward Moulton, in Lawrence County, and Dodge screening the movement by heading north in the hopes of distracting Forrest and Roddey. As Streight left Tuscumbia late on April 26, a heavy rainstorm made the roads virtually impassable, forcing him to make an unscheduled stop at Mount Hope in Lawrence County. There, Dodge informed Streight that the two would not meet at Moulton, as previously planned. Dodge reported that his command had driven Forrest to the north, thereby clearing a path for Streight to continue the raid unmolested. Dodge’s movements, however, had not deterred Forrest, who closely pursued the “Jackass Brigade.”

Grenville Dodge

Mules were not the only problem. The raid’s success also depended upon Brig. Gen. Grenville Dodge’s ability to screen Streight’s movements from Confederate cavalry commanded by General Forrest as well as cavalry led by Col. Phillip Roddey, both part of the Army of Tennessee. On April 19, 1863, Streight’s brigade boarded several boats at Nashville that transported the force southward on the Tennessee River and disembarked at Eastport, Mississippi. That night, a stampede scattered approximately 400 of the brigade’s mules into the surrounding countryside causing a delay as Streight waited in Eastport for a shipment of mules. Two days later, Streight rendezvoused with Dodge and his 8,000 cavalrymen, and moved toward Tuscumbia, in Colbert County. During the march, skirmishers who had detached from Forrest’s division impeded Federal movements. At Tuscumbia, Streight and Dodge separated, with Streight riding toward Moulton, in Lawrence County, and Dodge screening the movement by heading north in the hopes of distracting Forrest and Roddey. As Streight left Tuscumbia late on April 26, a heavy rainstorm made the roads virtually impassable, forcing him to make an unscheduled stop at Mount Hope in Lawrence County. There, Dodge informed Streight that the two would not meet at Moulton, as previously planned. Dodge reported that his command had driven Forrest to the north, thereby clearing a path for Streight to continue the raid unmolested. Dodge’s movements, however, had not deterred Forrest, who closely pursued the “Jackass Brigade.”

As Streight moved eastward, the morale of his command temporarily improved as dry weather and the capture of several Confederate supply wagons bolstered spirits. The mood changed, however, when U.S. Army scouts spotted Confederates moving along both their right and left flanks, threatening to surround the entire command. These movements led to the Battle of Day’s Gap, which took place in Cullman County near Sand Mountain. During this fight, Streight’s men thwarted Forrest’s attempt to surround him from the rear with a series of charges led by the Seventy-third Illinois and Fifty-first Indiana. Undeterred, a few hours later Forrest resumed the attack upon Streight, whose men dismounted and occupied a ridge along Hog Mountain in preparation for what they incorrectly believed was a larger force. Again Streight’s men repulsed several assaults and then resumed the march at an accelerated pace, which allowed them to successfully ambush a portion of Forrest’s cavalry near Blountsville (Blount County). As Streight’s men pressed toward Gadsden (Etowah County), Forrest’s constant presence behind the federal forces prevented Streight from resting his weary troops and mules, which proved too slow to outrun Forrest’s horsemen. In addition, their constant braying enabled Forrest’s scouts to detect Streight’s force from more than two miles away.

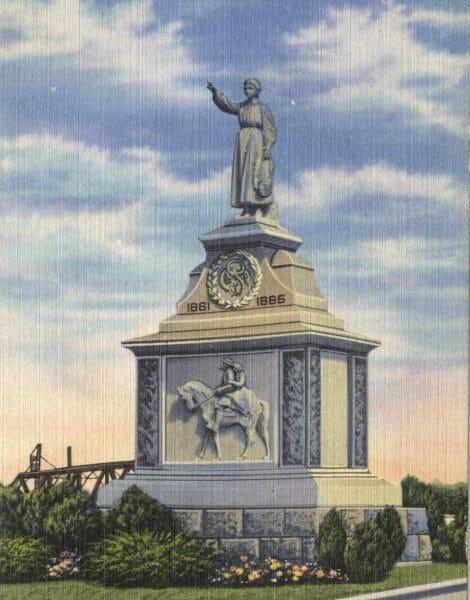

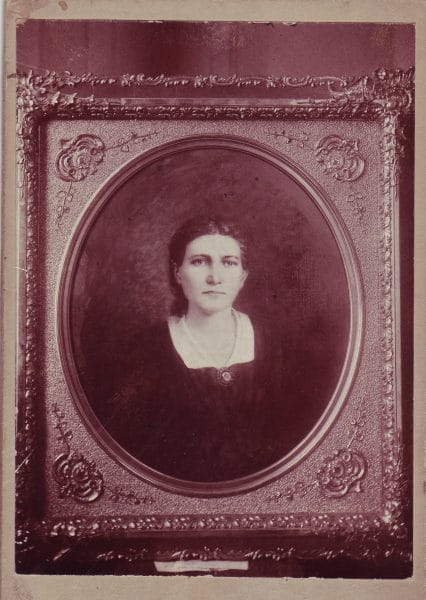

Emma Sansom

On the afternoon of May 2, Streight crossed Black Creek (located three miles from Gadsden) ahead of Forrest and burned the only nearby bridge, impeding the Confederate pursuit. Streight soon realized that his cavalry could not outrun Forrest for long and desperately needed to reach the city of Rome, Georgia. There, Streight intended to fight what he believed to be the numerically superior foe from behind some hastily prepared breastworks. Unbeknownst to him, the actions of two locals thwarted his plans. Unable to use the bridge to cross the swollen Black Creek, Forrest rode to a nearby home to find a guide. He found 16-year-old Emma Sansom, with whose guidance he located the ford, crossed it, and caught up with Streight’s force. Meanwhile, ferry operator John Wisdom came upon the troops having burned his ferry on the Coosa River at Gadsden and raced 67 miles to Rome, where he warned residents of the approaching U.S. troops. As a result of his actions, Rome’s inhabitants repelled a detachment of Streight’s cavalry sent to occupy a vital bridge crossing the Coosa River, thus blocking the only available route into the city. Streight then turned west toward Centre, in search of another crossing. His exhausted command, however, abandoned the search.

Emma Sansom

On the afternoon of May 2, Streight crossed Black Creek (located three miles from Gadsden) ahead of Forrest and burned the only nearby bridge, impeding the Confederate pursuit. Streight soon realized that his cavalry could not outrun Forrest for long and desperately needed to reach the city of Rome, Georgia. There, Streight intended to fight what he believed to be the numerically superior foe from behind some hastily prepared breastworks. Unbeknownst to him, the actions of two locals thwarted his plans. Unable to use the bridge to cross the swollen Black Creek, Forrest rode to a nearby home to find a guide. He found 16-year-old Emma Sansom, with whose guidance he located the ford, crossed it, and caught up with Streight’s force. Meanwhile, ferry operator John Wisdom came upon the troops having burned his ferry on the Coosa River at Gadsden and raced 67 miles to Rome, where he warned residents of the approaching U.S. troops. As a result of his actions, Rome’s inhabitants repelled a detachment of Streight’s cavalry sent to occupy a vital bridge crossing the Coosa River, thus blocking the only available route into the city. Streight then turned west toward Centre, in search of another crossing. His exhausted command, however, abandoned the search.

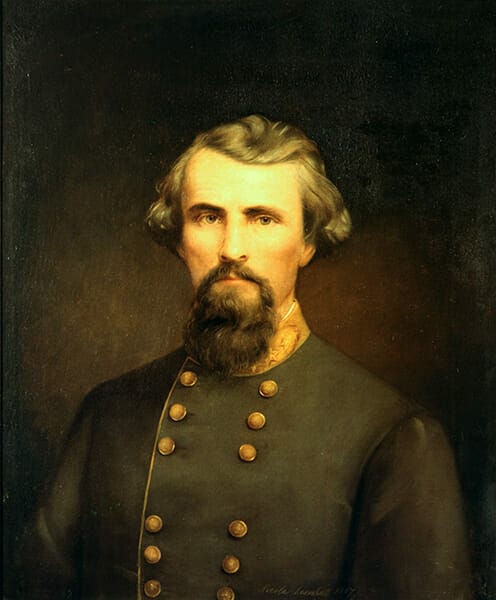

Nathan Bedford Forrest

At Cedar Bluff, Streight’s men stopped for a much-needed rest. Many of the cavalrymen had been walking due to the deaths of numerous mules. To make matters worse, during a recent skirmish the soldiers learned that the bulk of their ammunition was rendered useless due to its exposure to water. There at Cedar Bluff, Forrest and his 500 men surrounded Streight and his men. Rather than face possible annihilation, Streight decided to surrender his command. During the negotiations, Forrest craftily reaffirmed Streight’s misconception that the Confederates greatly outnumbered his brigade. In order to reinforce the ruse, Forrest’s artillery repeatedly rode in circles in and out of Streight’s view along a neighboring ridge. On May 3, 1863, Streight surrendered, convinced he had been captured by a numerically superior foe. When Forrest’s smaller division appeared following the surrender, Streight angrily demanded his men be allowed to renege their surrender, but Forrest refused. Defeat proved especially bitter for the soldiers of the First Alabama Cavalry (U.S.A.), who had risked their families and homes to defend the United States despite their state’s decision to secede. The Confederates transported Streight and the majority of his brigade to Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia. During the arduous trip, many of his weary malnourished soldiers succumbed to disease and many later died in prison, with approximately 200 lost in total. In 1864, Streight and 107 other prisoners escaped through an intricate system of tunnels.

Nathan Bedford Forrest

At Cedar Bluff, Streight’s men stopped for a much-needed rest. Many of the cavalrymen had been walking due to the deaths of numerous mules. To make matters worse, during a recent skirmish the soldiers learned that the bulk of their ammunition was rendered useless due to its exposure to water. There at Cedar Bluff, Forrest and his 500 men surrounded Streight and his men. Rather than face possible annihilation, Streight decided to surrender his command. During the negotiations, Forrest craftily reaffirmed Streight’s misconception that the Confederates greatly outnumbered his brigade. In order to reinforce the ruse, Forrest’s artillery repeatedly rode in circles in and out of Streight’s view along a neighboring ridge. On May 3, 1863, Streight surrendered, convinced he had been captured by a numerically superior foe. When Forrest’s smaller division appeared following the surrender, Streight angrily demanded his men be allowed to renege their surrender, but Forrest refused. Defeat proved especially bitter for the soldiers of the First Alabama Cavalry (U.S.A.), who had risked their families and homes to defend the United States despite their state’s decision to secede. The Confederates transported Streight and the majority of his brigade to Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia. During the arduous trip, many of his weary malnourished soldiers succumbed to disease and many later died in prison, with approximately 200 lost in total. In 1864, Streight and 107 other prisoners escaped through an intricate system of tunnels.

Streight’s Raid was an abysmal failure as a result of inadequate supplies, poor communication among Federal commanders, exaggerated estimates of Confederate forces and local Unionists, and bad luck. Whereas Nathan Bedford Forrest, and to a lesser degree Emma Sansom, are credited for foiling the raid, its failure had less to do with Confederate actions than the bungling mishaps of their federal counterparts. In the end, the raiders failed to disrupt the Army of Tennessee’s supply lines and had no impact upon the battles fought in middle Tennessee and northwest Georgia during the summer and fall of 1863, and they endured a humiliating defeat. In northern Alabama and northwest Georgia, accounts of Forrest’s heroics further elevated his already mythical status. In 1908, the city of Rome dedicated the first statue commissioned to honor the famed Confederate cavalryman and first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. Equally important, the state of Alabama and Confederacy acquired a wartime heroine, Emma Sansom, whose exploits would later reinforce postbellum notions that stressed the sacrifices and contributions of Confederate women during a war lost by southern men. The city of Gadsden erected a monument to Sansom in 1906. The Crooked Creek Civil War Museum in Vinemont, Cullman County, preserves the site of the skirmish and interprets its history.

Videos

Further Reading

- Hurst, Jack. Nathan Bedford Forrest: A Biography. New York: Vintage Press, 1993.

- Raines, Howell. Silent Cavalry: How Union Soldiers from Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta—And Then Got Written Out of History. New York: Crown, 2023.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006.

- Willett, Robert L., Jr. The Lightning Mule Brigade: Abel Streight’s 1863 Raid into Alabama. Carmel: Guild Press of Indiana, 1999.