H. L. Hunley Submarine

H. L. Hunley

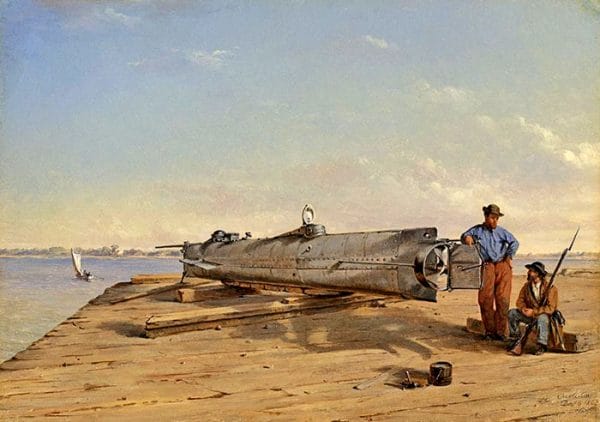

The H. L. Hunley was the first submarine to successfully sink an enemy ship in combat and was a remarkable vessel for the time in which it was constructed. The boat accurately reflected both the dangers and advantages of attacking enemy ships with underwater explosives. In February 1864, the Hunley launched from Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina, and attacked and sank the 1,800-ton steam-powered sloop-of-war USS Housatonic about two and a half miles out. Five crewman died on the Housatonic, but the Hunley sank with all hands. The submarine’s location was discovered in 1995, and the ship was raised in August 2000. The remains of all eight crewmen were found inside the submarine and were interred in Charleston’s Magnolia Cemetery in 2004.

H. L. Hunley

The H. L. Hunley was the first submarine to successfully sink an enemy ship in combat and was a remarkable vessel for the time in which it was constructed. The boat accurately reflected both the dangers and advantages of attacking enemy ships with underwater explosives. In February 1864, the Hunley launched from Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina, and attacked and sank the 1,800-ton steam-powered sloop-of-war USS Housatonic about two and a half miles out. Five crewman died on the Housatonic, but the Hunley sank with all hands. The submarine’s location was discovered in 1995, and the ship was raised in August 2000. The remains of all eight crewmen were found inside the submarine and were interred in Charleston’s Magnolia Cemetery in 2004.

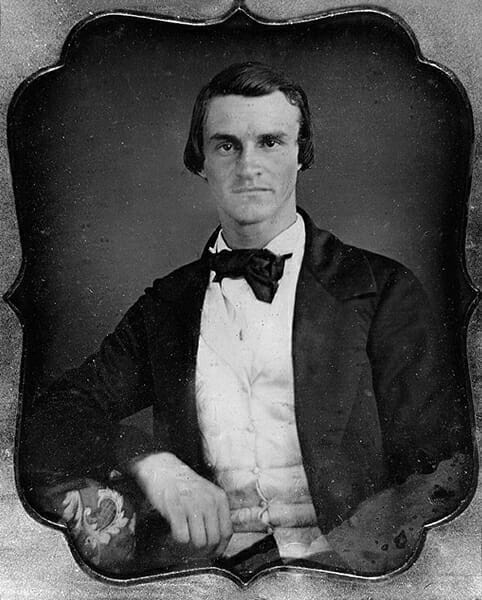

The Hunley was the third submarine vessel to be constructed under the direction of riverboat captain James McClintock, engineer Baxter Watson, and lawyer Horace Lawson Hunley, whom the boat was eventually named after. The first submarine, Pioneer, was constructed in New Orleans in late 1861 and early 1862. It was tested in the Mississippi River in February 1862 and was later taken to Lake Pontchartrain for further testing. It had to be scuttled in April when U.S. Navy admiral David Farragut’s fleet advanced upon the city of New Orleans.

James R. McClintock

The group moved its operations to the Park and Lyons Machine Shop in Mobile, Mobile County, where staff built a second submarine, the American Diver, sometimes referred to as the Pioneer II. The submarine’s development was supported by the Confederate Army, which assigned British-born lieutenant William Alexander of the Twenty-first Alabama Infantry to assist in the project. McClintock, Watson, and Hunley were among a group of developers and financiers in Mobile that was promised half of any valuable assets captured with the help of their inventions.

James R. McClintock

The group moved its operations to the Park and Lyons Machine Shop in Mobile, Mobile County, where staff built a second submarine, the American Diver, sometimes referred to as the Pioneer II. The submarine’s development was supported by the Confederate Army, which assigned British-born lieutenant William Alexander of the Twenty-first Alabama Infantry to assist in the project. McClintock, Watson, and Hunley were among a group of developers and financiers in Mobile that was promised half of any valuable assets captured with the help of their inventions.

The group experimented with electromagnetic propulsion, which was based on a primitive form of battery, as a means of propelling the boat, but the designers were unable to develop an engine powerful enough to move the boat through the water. In a letter to Matthew Maury, McClintock stated that the only alternative was to try a system powered with a hand crank. The submarine was ready for trials by January 1863, but it proved to be too slow and cumbersome to be of any practical use. The American Diver sank at the mouth of Mobile Bay during a storm in late February 1863 and was not recovered.

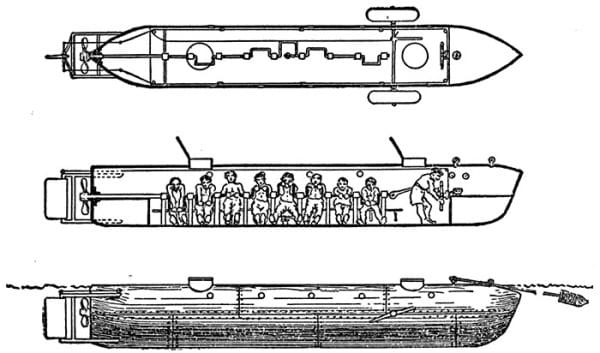

McClintock’s group began construction on the Hunley shortly after the loss of the second submarine. Early in its construction, the vessel was known as “the fish boat” or the “fish torpedo boat.” The builders at Park and Lyons had learned much from the failures of the first two submarines and incorporated design changes into the third submersible. The Hunley was almost 40 feet in length, had a beam (width) of almost four feet, and weighed approximately seven and a half tons. The submarine was powered by a hand crank that ran down the center of the boat and was attached to a propeller in the rear by a chain. The vessel was designed to carry a crew of nine, with eight on the crank shaft to power it and the ninth stationed in the forward bow to control dive planes, ballast, and navigation. The Hunley was privately financed, with a total cost of $15,000 for construction, none of which came from the Confederate government.

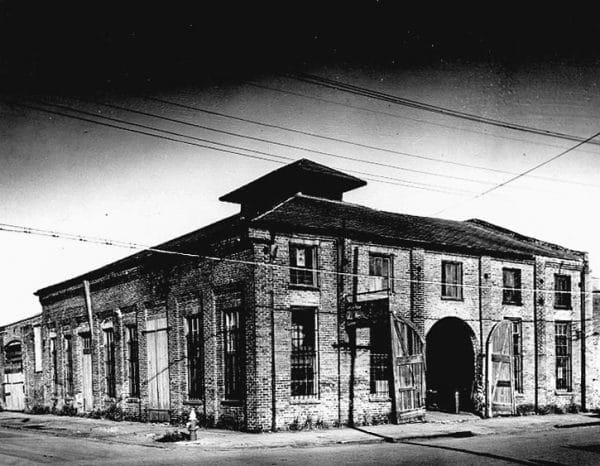

Park and Lyons Machine Shop

The submarine was launched into the harbor at the Theater Street Dock in Mobile in July 1863, and the crew immediately began testing exercises. The builders were satisfied with the performance of the boat and decided to arrange a demonstration of the submersible’s capabilities for Adm. Franklin Buchanan, the Confederate naval commander in Mobile. On July 31, 1863, a coal barge was towed to the middle of Mobile Bay and anchored as a test target for the submarine. The Hunley was armed with a floating contact torpedo (what we today call a mine) that was towed behind the submarine by a long rope. The vessel approached its target, dove underneath it, and dragged the torpedo into the hull of the barge. After the successful test, the military authorities in Mobile decided to ship the Hunley by rail to Charleston, South Carolina, where the federal fleet was bombarding the city on a daily basis.

Park and Lyons Machine Shop

The submarine was launched into the harbor at the Theater Street Dock in Mobile in July 1863, and the crew immediately began testing exercises. The builders were satisfied with the performance of the boat and decided to arrange a demonstration of the submersible’s capabilities for Adm. Franklin Buchanan, the Confederate naval commander in Mobile. On July 31, 1863, a coal barge was towed to the middle of Mobile Bay and anchored as a test target for the submarine. The Hunley was armed with a floating contact torpedo (what we today call a mine) that was towed behind the submarine by a long rope. The vessel approached its target, dove underneath it, and dragged the torpedo into the hull of the barge. After the successful test, the military authorities in Mobile decided to ship the Hunley by rail to Charleston, South Carolina, where the federal fleet was bombarding the city on a daily basis.

The submarine arrived in Charleston on August 12, 1863, and the crew engaged in several training missions with McClintock in command. Military authorities soon determined that McClintock was not aggressive enough, and by August 24th, the small ship had been seized by the Confederate authorities in Charleston and placed under the temporary command of the Confederate Navy. Navy lieutenant John A. Payne of the ironclad CSS Chicora was placed in command of the Hunley and a crew of seven volunteers from the Chicora and another Confederate ironclad, the CSS Palmetto State. The men, none of whom had experience in a submarine, began testing the boat during the day. On August 29, after only five days of training, Payne accidentally engaged the dive planes on the boat while the top hatches were open, and the submarine began to flood. Payne and two other crewmen escaped, but the five remaining crewmembers were stuck in the craft and drowned. It was an inauspicious start for the Hunley‘s career.

Pierre G. T. Beauregard

Crews recovered the vessel from its sinking location after several days, and Gen. Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard, senior Army commander at Charleston, gave command of the craft to Capt. Horace Lawson Hunley, one of the original investors and developers of the project. Hunley had little practical experience in piloting the craft, however, because he was in Mississippi for the majority of the time that it was being constructed in Mobile. Nevertheless, he and a volunteer crew from Park and Lyons were named as the new crew of the vessel.

Pierre G. T. Beauregard

Crews recovered the vessel from its sinking location after several days, and Gen. Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard, senior Army commander at Charleston, gave command of the craft to Capt. Horace Lawson Hunley, one of the original investors and developers of the project. Hunley had little practical experience in piloting the craft, however, because he was in Mississippi for the majority of the time that it was being constructed in Mobile. Nevertheless, he and a volunteer crew from Park and Lyons were named as the new crew of the vessel.

Around the beginning of October 1863, the men of the second crew began two weeks of training on the submersible. On the morning of October 15, Hunley commanded the boat as they made several practice dives near the CSS Indian Chief anchored in the Cooper River. The boat dove under the Indian Chief but never resurfaced, sinking with all hands, including Hunley. The Confederate Navy began a salvage operation immediately, recovering the craft several days later and renaming it in Hunley’s honor.

The submarine was placed under the command of First Lt. George E. Dixon of Company A of the Twenty-first Alabama Infantry. He was charged with enlisting another crew, cleaning and refitting the boat, and carrying out a successful attack against the U.S. Navy’s blockade off the coast of Charleston. He named Lt. William Alexander his executive officer, and the two proceeded to raise a third crew for the Hunley, many of whom had served on the Indian Chief, the same ship that had witnessed the submarine’s sinking.

H. L. Hunley Diagram

Despite the vessel’s previous failures, there was no shortage of volunteers, and Dixon and Alexander chose the most able-bodied men for the crew. By early December, the new crew had been assembled and began extensive training, day and night, on the submarine. During this trial period, the armament of the craft was modified so that the torpedo was mounted on a forward spar rather than towed from behind. This change meant that there was no longer a danger of the torpedo accidentally drifting into the Hunley during a combat operation and destroying the submarine. Because of the two previous accidents, Beauregard ordered that the vessel operate completely above the water, except when it was preparing to attack.

H. L. Hunley Diagram

Despite the vessel’s previous failures, there was no shortage of volunteers, and Dixon and Alexander chose the most able-bodied men for the crew. By early December, the new crew had been assembled and began extensive training, day and night, on the submarine. During this trial period, the armament of the craft was modified so that the torpedo was mounted on a forward spar rather than towed from behind. This change meant that there was no longer a danger of the torpedo accidentally drifting into the Hunley during a combat operation and destroying the submarine. Because of the two previous accidents, Beauregard ordered that the vessel operate completely above the water, except when it was preparing to attack.

By the middle of February, six months and two sinkings after her arrival in Charleston, Dixon was finally ready to engage an enemy ship. On the evening of February 17, 1864, the Hunley left its base at Breach Inlet on Sullivan’s Island and made its way into open waters in search of a target. Dixon most likely selected the USS Housatonic because of its close proximity to Sullivan’s Island, being only between two and a half to three miles off shore.

USS Housatonic

After an hour and a half, the small submarine finally reached the Housatonic and began its run at the ship. The officer of the deck spotted the Hunley as she approached the sloop-of-war and ordered the crew to fire on the submarine with rifled muskets and even a double-barreled shotgun. These projectiles bounced harmlessly off the iron hull of the submersible, however, and the submarine rammed into the Housatonic with the spar-mounted torpedo loaded with 135 pounds of gunpowder. The torpedo stuck into the side of the ship as the Hunley quickly reversed course. When the lanyard (a thin rope attached to the fuse) was pulled tight, the torpedo exploded in the stern of the Housatonic, perhaps even igniting some of the 7,000 pounds of gunpowder in the stern powder magazine onboard the ship. Within minutes, the Housatonic had sunk to the bottom, her large masts protruding above the shallow water line. Five crewman were killed, but the rest were either able to get to life boats or were rescued by other blockading ships that came to her aid.

USS Housatonic

After an hour and a half, the small submarine finally reached the Housatonic and began its run at the ship. The officer of the deck spotted the Hunley as she approached the sloop-of-war and ordered the crew to fire on the submarine with rifled muskets and even a double-barreled shotgun. These projectiles bounced harmlessly off the iron hull of the submersible, however, and the submarine rammed into the Housatonic with the spar-mounted torpedo loaded with 135 pounds of gunpowder. The torpedo stuck into the side of the ship as the Hunley quickly reversed course. When the lanyard (a thin rope attached to the fuse) was pulled tight, the torpedo exploded in the stern of the Housatonic, perhaps even igniting some of the 7,000 pounds of gunpowder in the stern powder magazine onboard the ship. Within minutes, the Housatonic had sunk to the bottom, her large masts protruding above the shallow water line. Five crewman were killed, but the rest were either able to get to life boats or were rescued by other blockading ships that came to her aid.

Contemporary accounts suggest that the Hunley survived her encounter with the Housatonic, as several men reported spotting a blue light, the signal for a successful attack, shortly after the explosion aboard the Housatonic. But the Hunley never returned from its mission. Once again, the submarine had sunk with all hands, and its location remained a mystery for more than 100 years, despite immediate recovery attempts.

Interest in the Hunley continued after the war. During the early twentieth century, famed showman Phineas “P. T.” Barnum offered the monumental reward of $100,000 to anyone who could find it, but no one ever claimed the prize. It was not until 1970 that underwater archeologist E. Lee Spence located the site of the Hunley wreck, revisiting it twice more in the 1970s. In early 1995, Spence published a book describing his find, and in April of that year, an expedition led by diver Ralph Wilbanks as a joint effort of the private National Underwater and Marine Agency and the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology found the ship.

On August 8, 2000, a large team of professional underwater archeologists, with the assistance of the federal government and the state of South Carolina, raised the remains of the Hunley with the barge Karlissa B. There was great debate in the state as to who should take charge of the submarine and where it should be displayed. The recovery effort ended when the boat was sent to the Warren Lasch Conservation Center of Clemson University, located at the old Charleston Navy Yard.

During the conservation, the remains of the eight crewman were recovered, and all were found in their assigned positions onboard the vessel, suggesting that there was no panic at the time the boat went down. Recent analysis of the events surrounding the sinking suggests that the men most probably died quickly from internal injuries caused by shock waves from the explosion of the torpedo.

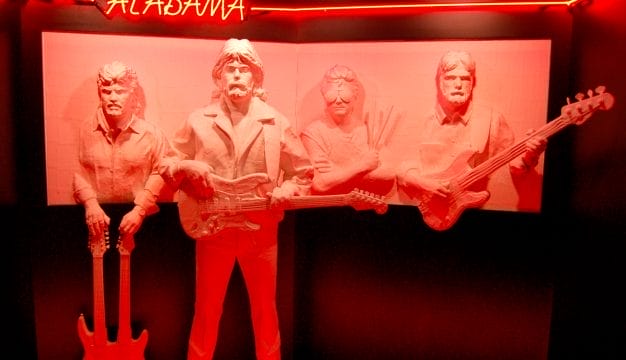

On April 17, 2004, the crew was buried in a public ceremony in Charleston’s Magnolia Cemetery next to the other crewmen who had drowned on the submarine some 140 years earlier. The restored Hunley is on view at the Warren Lasch Conservatory, and visitors can see the submarine on weekend tours. The building that housed the Park and Lyons Machine Shop still stands on the corner of Water and State streets in Mobile, and there is a replica of the Hunley on display at the USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park.

Further Reading

- Conlin, David L., ed. USS Housatonic Site Assessment. National Park Service, Naval Historical Center, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2005.

- Hicks, Brian, and Schuyler Kropf. Raising the Hunley. New York: Ballantine Books, 2002.

- Ragan, Mark K. The Hunley. Orangeburg, S.C.: Sandlapper Publishing, 2006.

- Still, William N., Jr., ed. The Confederate Navy. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1997.