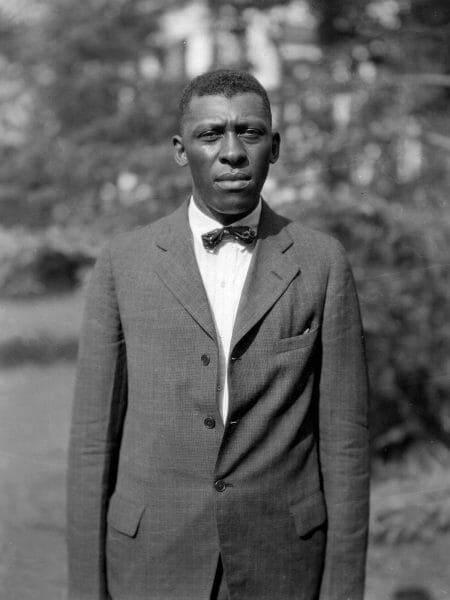

Thomas Monroe Campbell

Thomas Monroe Campbell (1883-1956) was a pioneer in the fields of agricultural education and extension work. A protégé of famed scientist George Washington Carver, Campbell trained at Tuskegee Institute and then worked to bring modern agriculture methods to the rural black farmers of Alabama as the nation’s first African American agricultural extension agent. In addition to promoting modern farming methods, Campbell also galvanized rural support for World War II, and served as an international consultant on farming methods and rural life in Africa.

Thomas Monroe Campbell

The son of an itinerant Methodist preacher and tenant farmer, Thomas Monroe Campbell was born in Elbert County, Georgia, on February 11, 1883. He worked with his tenant-farmer father and several white farmers until he was fifteen. Campbell briefly attended a local school in 1898 and in January of the following year he set out for Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, where his brother was attendeding school. Campbell did not do well on the entrance exam, however, and instead took non-matriculated courses at night. He worked hard to improve his grades, took a number of courses in agriculture, and graduated in spring 1906. In recognition of Campbell’s skills and expertise, Tuskegee president Booker T. Washington and science professor Carver petitioned the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to appoint Campbell as its first black extension agent, a position that would allow him to educate rural farmers in advanced farming and land-management methods. They hoped that Campbell’s skills and his familiarity with local communities would help to improve the economic conditions of black farmers in the South by demonstrating science-based agricultural practices to them. USDA leaders agreed and appointed him the farm demonstration agent for Macon County. Campbell’s first assignment was to manage Tuskegee’s Movable School of Agriculture, also known

Thomas Monroe Campbell

The son of an itinerant Methodist preacher and tenant farmer, Thomas Monroe Campbell was born in Elbert County, Georgia, on February 11, 1883. He worked with his tenant-farmer father and several white farmers until he was fifteen. Campbell briefly attended a local school in 1898 and in January of the following year he set out for Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, where his brother was attendeding school. Campbell did not do well on the entrance exam, however, and instead took non-matriculated courses at night. He worked hard to improve his grades, took a number of courses in agriculture, and graduated in spring 1906. In recognition of Campbell’s skills and expertise, Tuskegee president Booker T. Washington and science professor Carver petitioned the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to appoint Campbell as its first black extension agent, a position that would allow him to educate rural farmers in advanced farming and land-management methods. They hoped that Campbell’s skills and his familiarity with local communities would help to improve the economic conditions of black farmers in the South by demonstrating science-based agricultural practices to them. USDA leaders agreed and appointed him the farm demonstration agent for Macon County. Campbell’s first assignment was to manage Tuskegee’s Movable School of Agriculture, also known

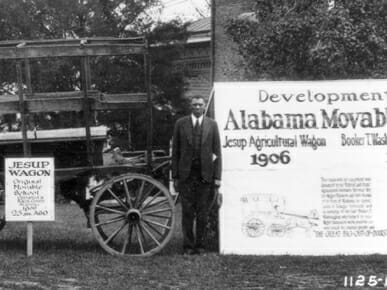

Tuskegee Institute Movable School

as the Jesup Agricultural Wagon, which was equipped with seeds, fertilizers, different kinds of plows and planters, and other farm appliances. Campbell took the wagon over the rough, dusty roads to rural communities in Macon County, where he demonstrated improved methods of farming and instilled in the minds of poor black farm families a vision of a better life.

Tuskegee Institute Movable School

as the Jesup Agricultural Wagon, which was equipped with seeds, fertilizers, different kinds of plows and planters, and other farm appliances. Campbell took the wagon over the rough, dusty roads to rural communities in Macon County, where he demonstrated improved methods of farming and instilled in the minds of poor black farm families a vision of a better life.

Campbell’s work was praised by Washington and his superiors at the USDA, and in 1908 he was promoted to district agent for Alabama and bordering states and began conducting farmers’ conferences and agricultural fairs. By 1914, Campbell had assisted 11 southern states in appointing black farm agents and home demonstration agents. World War I provided Campbell and these other agents an opportunity to support the war effort by encouraging food production, assisting local recruiting offices, raising funds for the Red Cross, locating horses and mules for the army, and securing farm labor. Campbell served as a speaker to black audiences for the Four Minute Men, a group of volunteer inspirational speakers whose goal was to foster patriotism for the war effort. He also organized “Uncle Sam’s Saturday Service League,” which encouraged black farmers and laborers to work an extra half or whole day on Saturday during the war. By the time the war ended, the number of black extension agents in the South had increased to 459, and the USDA promoted Campbell to field agent, supervising black extension agents in the Lower South.

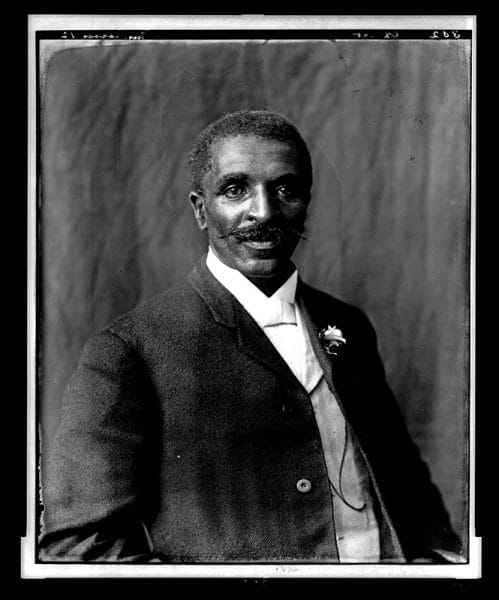

George Washington Carver

Campbell’s leadership qualities led several black colleges to offer him administrative positions during the 1920s, but he chose to continue his work with the extension service. The economic depression of the 1930s brought disaster to black farmers and spending cuts to the black extension service, and Campbell sought help from New Deal legislation. He involved himself with relief work, serving on the Alabama Rehabilitation Committee and the Black Belt Improvement League. His influence increased during the 1930s, when he began broadcasting a radio program aimed at black farmers that featured extension news and idea. He also spoke several times over nationwide radio from Washington, D.C., on topics such as extension work in African American communities, the Movable School, low-cost housing, and 4-H work.

George Washington Carver

Campbell’s leadership qualities led several black colleges to offer him administrative positions during the 1920s, but he chose to continue his work with the extension service. The economic depression of the 1930s brought disaster to black farmers and spending cuts to the black extension service, and Campbell sought help from New Deal legislation. He involved himself with relief work, serving on the Alabama Rehabilitation Committee and the Black Belt Improvement League. His influence increased during the 1930s, when he began broadcasting a radio program aimed at black farmers that featured extension news and idea. He also spoke several times over nationwide radio from Washington, D.C., on topics such as extension work in African American communities, the Movable School, low-cost housing, and 4-H work.

Also during the 1930s, Campbell received a great deal of recognition for his contributions to the extension service, including the first Harmon Award (named for philanthropist William Harmon) ever presented for the newly created category of distinguished service in the field of farming and rural life. The General Education Board, endowed by New York industrialist John D. Rockefeller, awarded Campbell a fellowship for graduate study at Cornell University in 1932, but he refused the offer. Tuskegee Institute honored him in 1936 with an honorary Master of Science degree, and in 1938 he was elected to the Eugene Field Society, a national association of authors and journalists, in recognition of his numerous journal and newspaper articles and the publication of his book The Movable School Goes to the Negro Farmer in 1936.

Jesup Wagon

During the 1940s, Campbell’s growing prominence brought him more opportunities to promote his extension work outside of the South. During World War II, Campbell continued his official duties and also devoted time to war-bond drives and served on the USDA’s National Advisory Committee for Community Service Projects. In 1944 he was appointed to a three-member commission to West Africa that was charged with studying rural life in Liberia, Belgian Congo (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), Nigeria, Gold Coast (now Ghana), Sierra Leone, and French Cameroons (now Cameroon). When the commissioners returned to the United States in March 1945 after a six-month stay, they wrote and published a description of their trip titled Africa Advancing: A Study of Rural Education and Agriculture in West Africa and the Belgian Congo.

Jesup Wagon

During the 1940s, Campbell’s growing prominence brought him more opportunities to promote his extension work outside of the South. During World War II, Campbell continued his official duties and also devoted time to war-bond drives and served on the USDA’s National Advisory Committee for Community Service Projects. In 1944 he was appointed to a three-member commission to West Africa that was charged with studying rural life in Liberia, Belgian Congo (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), Nigeria, Gold Coast (now Ghana), Sierra Leone, and French Cameroons (now Cameroon). When the commissioners returned to the United States in March 1945 after a six-month stay, they wrote and published a description of their trip titled Africa Advancing: A Study of Rural Education and Agriculture in West Africa and the Belgian Congo.

Despite his many wartime duties and activities, Campbell continued to raise more money for extension services and increase the number of black extension agents in the South. When Campbell retired on February 28, 1953, after 47 years of service, the number of black extension workers had reached 850. Campbell remained an active participant in conferences, meetings, workshops, Boy Scouts, and activities on the Tuskegee Institute campus. In 1954 he served as narrator for and appeared in the film “The Negro Farmer,” produced by Liggett and Myers Tobacco Company. The Ford Foundation awarded Campbell a grant in 1953 to write a book about the problems and progress of black farmers in the United States, but he died before the work was completed. Campbell became publicly more critical of racial discrimination in the South in his retirement. In 1954 he wrote in his personal journal, “The Negro in the U.S. is more conscious than ever of the fact that he is not wholly and equably sharing in the ‘American Way of Life.’ . . . In other words the Negro knows deep down in his heart he still does not belong.”

Tuskegee Movable School Agents

Campbell married nurse Anna Marie Ayers Campbell in 1912, and the couple had six children, five of whom went on to successful careers. His son Bill was a colonel in the air force and served with the Tuskegee Airmen in World War II. His daughter Abbie Noel also served in World War II as a captain in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) and was the executive officer of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion. A sixth child, son Carver (named for George Washington Carver), died in 1936 while pursuing graduate work in agriculture at Cornell University in New York State. Campbell was a man of his times, and he worked within the existing structures of southern society for changes that he believed were best for all rural farm families in the South. He devoted his life to helping rural black people in the South achieve economic independence, more efficient and effective agricultural production, and a higher standard of living. He was an active and energetic man whose work did not end until his death on February 8, 1956.

Tuskegee Movable School Agents

Campbell married nurse Anna Marie Ayers Campbell in 1912, and the couple had six children, five of whom went on to successful careers. His son Bill was a colonel in the air force and served with the Tuskegee Airmen in World War II. His daughter Abbie Noel also served in World War II as a captain in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) and was the executive officer of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion. A sixth child, son Carver (named for George Washington Carver), died in 1936 while pursuing graduate work in agriculture at Cornell University in New York State. Campbell was a man of his times, and he worked within the existing structures of southern society for changes that he believed were best for all rural farm families in the South. He devoted his life to helping rural black people in the South achieve economic independence, more efficient and effective agricultural production, and a higher standard of living. He was an active and energetic man whose work did not end until his death on February 8, 1956.

Additional Resources

Austin, Deborah W. “Thomas Monroe Campbell and the Development of Negro Agriculture Extension Work, 1883-1956.” Master’s thesis, Auburn University, 1975.

Thomas M. Campbell Papers, Tuskegee University Archives, Tuskegee University, Tuskegee, Alabama.

Campbell, Thomas M. The Movable School Goes to the Negro Farmer. Tuskegee, Ala.: Tuskegee Institute Press, 1936.

———. The School Comes to the Farmer: The Autobiography of T. M. Campbell. London: Longmans, Green, 1947.

———. The Saturday Service League. Circular 40. Auburn: Alabama Polytechnic Institute, 1920.

———. U.S. Farm Demonstration Work Among Negroes in the South. Tuskegee, Ala.: Tuskegee Institute Press, 1915

Davis, Jackson, Thomas M. Campbell, and Margaret Wrong. Africa Advancing: A Study of Rural Education and Agriculture in West Africa and Belgian Congo. New York: Friendship Press, 1945.

James, Felix. “The Tuskegee Institute Movable School, 1906-1923.” Agricultural History 45 (July 1971): 201-9.

Jones, Allen W. “Thomas M. Campbell: Black Agricultural Leader of the New South.” Agricultural History 53 (January 1979): 42-59.

———. “The South’s First Black Farm Agents.” Agricultural History 50 (October 1976): 636-44.

———. “The Role of Tuskegee Institute in the Education of Black Farmers.” Journal of Negro History 60 (April 1975): 252-67.