Edgar Daniel "E. D." Nixon

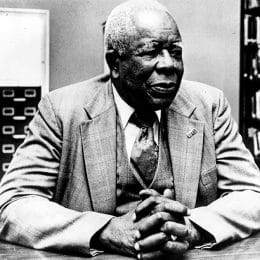

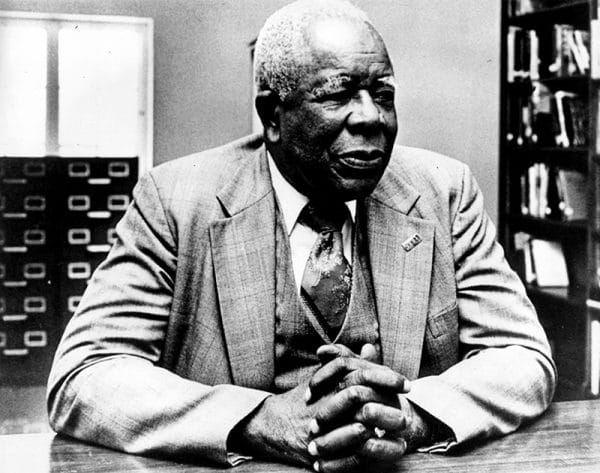

E. D. Nixon, 1984

E. D. Nixon (1899-1987) was a long-time leader of the civil rights movement in Alabama. He worked tirelessly to increase the number of registered black voters in Montgomery and was one of the key organizers of the Montgomery Improvement Association and the Montgomery Bus Boycott. He also helped bail Rosa Parks out of jail after she was arrested for violating segregation laws. Heavily influenced by his membership in the largely African American Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), Nixon became an outspoken activist for African American voting rights and employment opportunities in the years between World War II and the early years of the civil rights movement in the mid-1950s. Nixon also was the first black candidate in the twentieth century to run for a seat on Montgomery County’s Democratic Executive Committee in 1954. He lost his bid but was allowed to question candidates for the city commission, which functioned as Montgomery’s central government, about issues of race the following year.

E. D. Nixon, 1984

E. D. Nixon (1899-1987) was a long-time leader of the civil rights movement in Alabama. He worked tirelessly to increase the number of registered black voters in Montgomery and was one of the key organizers of the Montgomery Improvement Association and the Montgomery Bus Boycott. He also helped bail Rosa Parks out of jail after she was arrested for violating segregation laws. Heavily influenced by his membership in the largely African American Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), Nixon became an outspoken activist for African American voting rights and employment opportunities in the years between World War II and the early years of the civil rights movement in the mid-1950s. Nixon also was the first black candidate in the twentieth century to run for a seat on Montgomery County’s Democratic Executive Committee in 1954. He lost his bid but was allowed to question candidates for the city commission, which functioned as Montgomery’s central government, about issues of race the following year.

Edgar Daniel Nixon was born on July 12, 1899, to Wesley M. Nixon and Sue Ann Chappell Nixon in Lowndes County and spent his adolescent years in Montgomery. Nixon’s mother died when he was a boy, and he and his seven siblings lived with several family members as youths. He received little formal education, but at six feet, four inches tall and possessing a charismatic spirit and a deep baritone voice, he had a natural ability to organize and to rally people around a cause. In 1926, Nixon married Alease Nixon, with whom he had son E. D. Nixon Jr. (1928-2011), an actor who went by the stage name Nick La Tour.

In the early 1920s, Nixon began working as a Pullman sleeping car porter. Porters assisted passengers boarding trains and also carried their luggage. Sleeping car porters assisted those passengers who took residence in the sleeping compartments of the trains. Widely considered desirable among African Americans for the high wages and travel opportunities they offered, Pullman porter jobs allowed these men to enter the small middle class of black America. During his travels on the trains, Nixon was exposed to the less restrictive communities and social practices outside the Deep South, with its entrenched Jim Crow racial policies. It also introduced him to the BSCP, a union that advocated better wages and working conditions for black railway workers, and acquainted him with its influential leader, A. Phillip Randolph. It was through these connections and experiences that Nixon was inspired to become an activist. Nixon quickly became a disciple of Randolph, and his philosophies greatly influenced Nixon’s later civil-rights work in Alabama. Randolph believed that the civil-rights movement was “wholly inadequate” to rectify the racial problems in America and more governmental action was needed. In 1934, Alease died, and Nixon married Arlet Nixon, became a fixture at his side in the Montgomery civil-rights movement

During the 1940s, Nixon’s community activism crystallized in Montgomery, where he and a group from the Madison Park community in North Montgomery organized the Alabama Voters League and worked to increase voter registration among the city’s African American population. Through the Alabama Voters League, the outspoken Nixon organized and launched a march of about 750 people on the Montgomery County Municipal Courthouse in 1944 to raise awareness of impediments to black voting. In 1945, he was elected as the president of the Montgomery chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and just two years later became the state president of the organization.

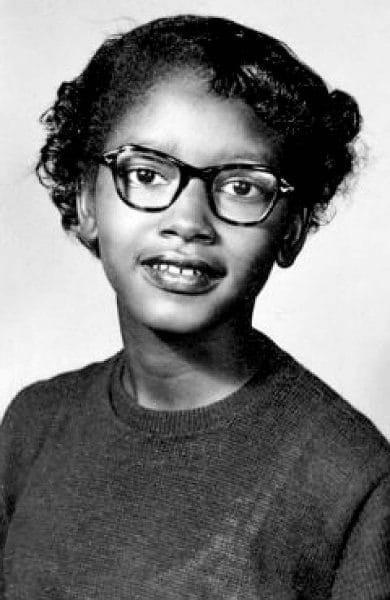

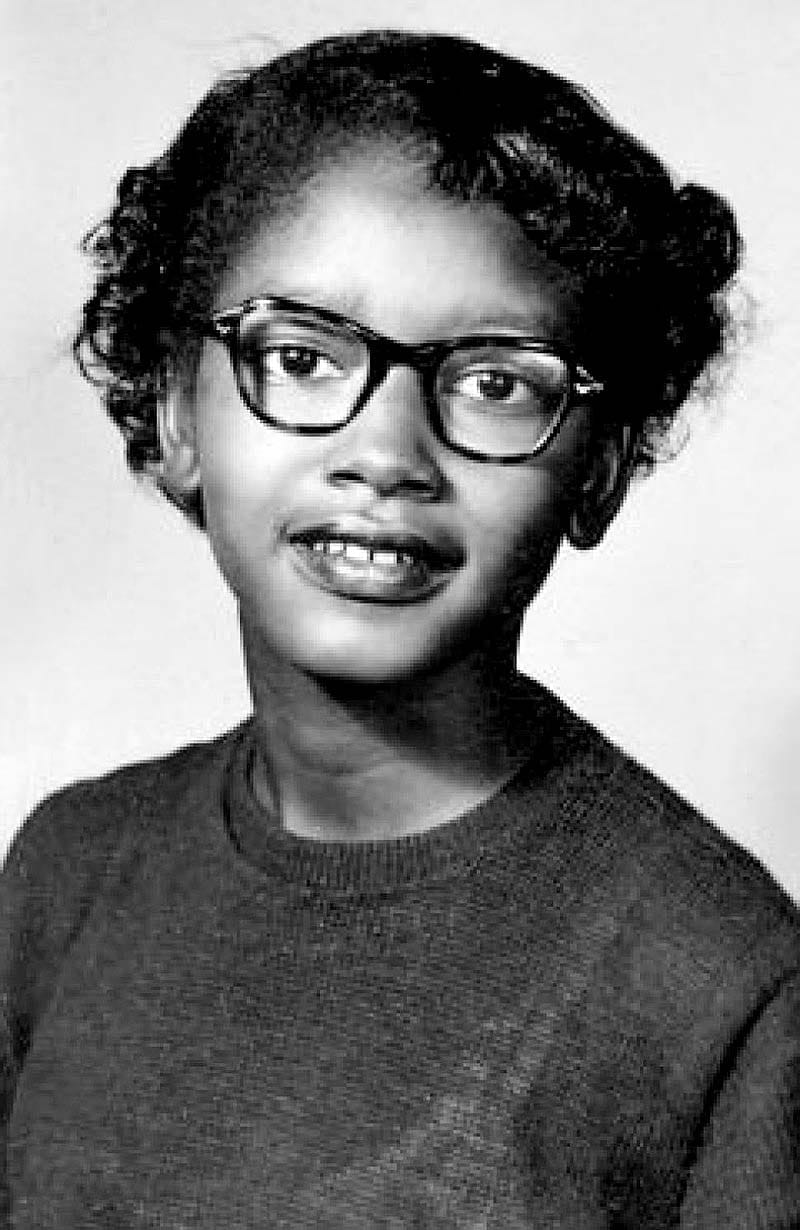

Nixon was politically astute and negotiated successfully with white city leaders to gain marginal advances in employment for blacks in city governmental agencies. During the 1950s, Nixon was instrumental in convincing the Montgomery Police Department to hire blacks by agreeing to support a white candidate who was sympathetic to the fight for black civil rights. Also around this time, Nixon began to openly question the segregated seating restrictions on city buses and the refusal of bus companies to employ black drivers. He and other members of the Montgomery branch of the NAACP began to look for a test case to challenge the legality of Montgomery’s segregated transportation system. When Claudette Colvin, a 15-year-old from Booker T. Washington High School, was arrested for refusing to surrender her seat to a white man, Nixon wondered if the arrest could serve as the case that could challenge the legality of Alabama’s segregated buses. Nixon consulted with attorney and civil-rights activist Fred Gray and others to analyze the merits of a case and to determine if Colvin could stand the scrutiny of being a lead plaintiff. Nixon decided that Colvin was not mature enough to handle the pressures associated with such a landmark case and was not from a middle-class family, which would garner more public sympathy.

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks, a seamstress and secretary for the NAACP in Montgomery, was arrested for refusing to surrender her seat to a white man. Nixon was notified of the arrest, and when he telephoned to inquire about Parks’s arrest, his inquiry was met with racial epithets, and the police refused to speak with him. Undeterred, Nixon sought help from civil-rights attorney Clifford Durr and his wife Virginia to gain information about the arrest and accompany him to post bail for Parks. Nixon put his house up as bond collateral for her release.

Nixon consulted with the Durrs, Gray, and other local black leaders, and they decided that Parks’s arrest would serve as the case to challenge the state’s segregation policy in Montgomery. A short time later, Nixon and a group of Montgomery-area clergy and civic leaders, including civil-rights leader Ralph Abernathy, founded the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA). Minister and civil-rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was elected president of the organization. MIA provided a focal point for activism in Montgomery’s black community and its leaders organized the Montgomery Bus Boycott, in which the city’s black citizens refused to ride public transportation for an astounding 381 days. During the boycott, Martin Luther King Jr.’s home was bombed on January 30, 1956, and Nixon’s home was bombed just two days later, although this event did not receive nearly as much attention as the King bombing.

Clifford and Virginia Durr

After the success of the boycott, which lasted more than a year, MIA continued to serve the community by conducting voter-registration drives and hosting workshops on nonviolent protest methods. Nixon had been elected as the treasurer of MIA at the group’s founding, but later quit the organization after a dispute with some of MIA’s leaders. His departure likely related to the class-based schism in leadership within the black community. Most of the leadership positions in the movement were held by well-educated middle-class black men, whereas less-educated and lower-class black men and most women were relegated to support positions. Nixon opposed this division and on June 3, 1957, disassociated himself from the organization in protest. Economically Nixon was middle class, but was considered of lower-class status because of his lack of formal education. Despite Nixon’s departure from MIA, he continued to be an activist for the black community, although never to the degree of his involvement with the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Clifford and Virginia Durr

After the success of the boycott, which lasted more than a year, MIA continued to serve the community by conducting voter-registration drives and hosting workshops on nonviolent protest methods. Nixon had been elected as the treasurer of MIA at the group’s founding, but later quit the organization after a dispute with some of MIA’s leaders. His departure likely related to the class-based schism in leadership within the black community. Most of the leadership positions in the movement were held by well-educated middle-class black men, whereas less-educated and lower-class black men and most women were relegated to support positions. Nixon opposed this division and on June 3, 1957, disassociated himself from the organization in protest. Economically Nixon was middle class, but was considered of lower-class status because of his lack of formal education. Despite Nixon’s departure from MIA, he continued to be an activist for the black community, although never to the degree of his involvement with the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

By the late 1960s, Nixon had lost much of his political clout and faded into the background without any recognition or fanfare for his major contributions to the civil-rights movement. He worked as the recreation director of a public housing project after the 1960s in relative obscurity, although he did receive a few awards for his civil-rights work in his later years. Nixon died on February 25, 1987 at Baptist Hospital in Montgomery. People from all walks of life came to the funeral of this civil-rights icon at Bethel Baptist Church in Montgomery. Nixon generally has been overlooked by historians, and his importance in the bus boycott has been downplayed by some participants associated with it. Long-overdue recognition was finally bestowed on this early civil-rights hero when the Montgomery County Public School System named an elementary school in his honor in 2001.

Further Reading

- Branch, Taylor. Part the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63. New York: Simon Schuster, 1988.

- Carson, Clayborne, David Garrow, Gerald Gill, Vincent Harding, and Darlene Clark Hine. The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader, Documents, Speeches, and Firsthand Accounts, From the Black Freedom Struggle. New York: Penguin Books, 1987.

- E. D. Nixon Collection, Special Collections, Levi Watkins Library, Alabama State University, Montgomery.

- Farrell, Herman Daniel, and Timothy J. Sexton, writers. Boycott. New York: HBO Home Video, 2001.

- Gray, Fred. Bus Ride to Justice. Montgomery, Ala.: New South Books, 1995.

- Houston, Robert. Mighty Times: The Legacy of Rosa Parks. Montgomery: Southern Poverty Law Center, Teaching Tolerance Project, 2002.