Hodges Meteorite Strike (Sylacauga Aerolite)

Hodges Meteorite Strike

On November 30, 1954, a meteorite crashed through the roof of a home in a then-unincorporated area near Sylacauga, Talladega County, striking resident Ann E. Hodges (1923-1972). The area was later incorporated as the town of Oak Grove. Hodges was the first person ever to have been injured by a meteorite, and the event caused a nationwide media sensation and a year-long legal battle. The meteorite, which weighs about eight and one-half pounds, is on permanent display at the Alabama Museum of Natural History at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa.

Hodges Meteorite Strike

On November 30, 1954, a meteorite crashed through the roof of a home in a then-unincorporated area near Sylacauga, Talladega County, striking resident Ann E. Hodges (1923-1972). The area was later incorporated as the town of Oak Grove. Hodges was the first person ever to have been injured by a meteorite, and the event caused a nationwide media sensation and a year-long legal battle. The meteorite, which weighs about eight and one-half pounds, is on permanent display at the Alabama Museum of Natural History at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa.

Hodges was napping on her living-room couch at mid-day when the meteorite came through the ceiling, hit a console radio, and smashed into her hip. Awakened by the pain and noise, she thought the gas space heater had exploded. When she noticed a grapefruit-sized rock lying on the floor and a ragged hole in the roof, she assumed children were the culprits. Her mother, Ida Franklin, rushed outside and saw only a black cloud in the sky. Alabamians in and around the area saw the event from a different perspective, with many reporting that they had seen a fireball in the sky and heard a tremendous explosion that produced a white or brownish cloud. Most assumed it involved an airplane accident.

Walter B. Jones

Sylacauga Chief of Police W. D. Ashcraft and Sylacauga mayor Ed Howard responded to the call from the Hodges’s residence. They had Ann Hodges examined by physician Moody Jacobs, who determined that although her hip and hand were swollen and painful, there was no serious damage. (He later checked her into the hospital for several days to spare her from all the excitement.) Ashcraft and Howard showed the rock to geologist George Swindel, who was conducting fieldwork in the area. He tentatively identified the object as a meteorite. That evening they turned the meteorite over to officers from Maxwell Field, Montgomery, who took it to Air Force intelligence authorities for analysis. Air Force specialists identified it as a meteorite and sent it to curators at the Smithsonian Institution, who, delighted with their windfall, declined to send it back to Alabama. Not until Alabama congressman Kenneth Roberts intervened was the meteorite finally returned to the state, where it soon became the focus of a highly public legal battle.

Walter B. Jones

Sylacauga Chief of Police W. D. Ashcraft and Sylacauga mayor Ed Howard responded to the call from the Hodges’s residence. They had Ann Hodges examined by physician Moody Jacobs, who determined that although her hip and hand were swollen and painful, there was no serious damage. (He later checked her into the hospital for several days to spare her from all the excitement.) Ashcraft and Howard showed the rock to geologist George Swindel, who was conducting fieldwork in the area. He tentatively identified the object as a meteorite. That evening they turned the meteorite over to officers from Maxwell Field, Montgomery, who took it to Air Force intelligence authorities for analysis. Air Force specialists identified it as a meteorite and sent it to curators at the Smithsonian Institution, who, delighted with their windfall, declined to send it back to Alabama. Not until Alabama congressman Kenneth Roberts intervened was the meteorite finally returned to the state, where it soon became the focus of a highly public legal battle.

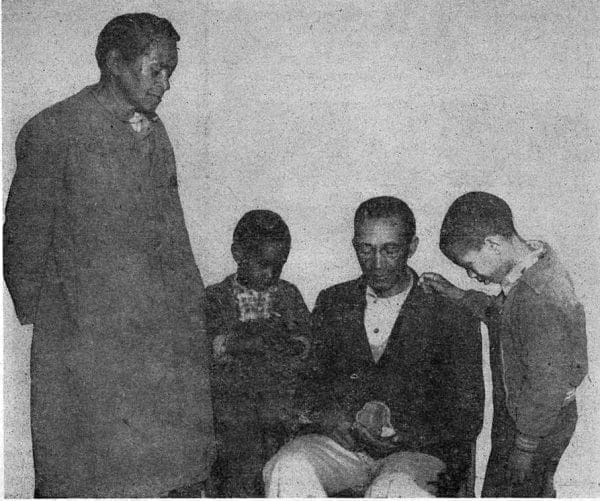

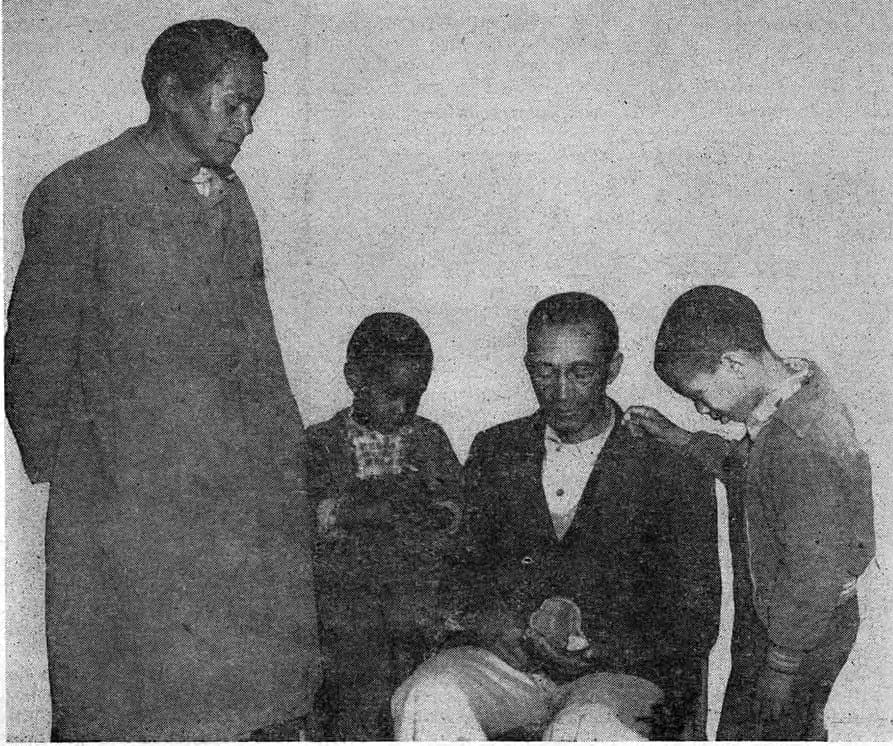

By nightfall some 200 reporters and sightseers filled the Hodges’s yard, and Ann’s husband, Hewlett, arriving home late, was upset by the crowd. Television, radio and newspaper excitement lasted for weeks, highlighted by a very public dispute between the Hodges and Birdie Guy, who owned the home in which the Hodges lived as renters. Facing repair expenses for the damaged house, Guy was advised by her attorney that legal precedent had established that meteorites were the property of the landowner, and she sued for possession of the rock. The Hodges threatened to counter-sue for Ann’s injuries, and the outraged public sided with her. Before it went to trial, cooler heads prevailed and after a modest private settlement, Guy gave up her claim on the meteorite to the Hodges.

Hodges Meteorite Display

Ann Hodges was barraged by publicity and was featured in Life magazine displaying a sizable bruise on her hip. She also was persuaded to go to New York to appear on Gary Moore’s TV quiz show I’ve Got a Secret. Her story appeared in the Sunday magazine supplement of many newspapers and in major magazines. Hewlett Hodges believed that the couple stood to make a fortune from the incident. He refused what he considered an inadequate offer for the meteorite from the Smithsonian Institution, claiming he had received other offers as high as $5,500. In the end, Ann Hodges, not knowing how to bargain with the media, earned at most only a few hundred dollars from the incident that had made her famous. By 1956, the bad publicity surrounding the lawsuit ended the monetary offers, and she donated the meteorite to the Alabama Museum of Natural History, where it remains.

Hodges Meteorite Display

Ann Hodges was barraged by publicity and was featured in Life magazine displaying a sizable bruise on her hip. She also was persuaded to go to New York to appear on Gary Moore’s TV quiz show I’ve Got a Secret. Her story appeared in the Sunday magazine supplement of many newspapers and in major magazines. Hewlett Hodges believed that the couple stood to make a fortune from the incident. He refused what he considered an inadequate offer for the meteorite from the Smithsonian Institution, claiming he had received other offers as high as $5,500. In the end, Ann Hodges, not knowing how to bargain with the media, earned at most only a few hundred dollars from the incident that had made her famous. By 1956, the bad publicity surrounding the lawsuit ended the monetary offers, and she donated the meteorite to the Alabama Museum of Natural History, where it remains.

Ann Hodges’s physical injuries healed, but she was never able to recover emotionally from her brush with celebrity. She and Hewlett separated in 1964. They both agreed that the emotional impact and disruption caused by the meteorite were contributing factors and said they wished it had never happened. Ann Hodges’s health declined and in 1972, after some years as an invalid, she died. She is buried in the cemetery behind Charity Baptist Church in Hazel Green, Madison County.

Probably the only major figure in the entire Sylacauga meteorite story to claim a satisfactory ending was Julius K. McKinney, a farmer who lived near the Hodges. On December 1, 1954, the day after Ann Hodges was struck, he discovered a second fragment of the meteorite in the middle of a dirt road. McKinney was able to sell his rock to the Smithsonian for enough to purchase a small farm and a used car. This fragment is on display at the Smithsonian Institution, but the label strangely does not acknowledge its more famous Alabama sibling. On May 22, 2010, the town of Oak Grove dedicated a historical marker at the site of the meteorite strike. In honor of the occasion, the UA Museum of Natural History sent the meteorite to the town for the day as part of the festivities.