Jesse Owens

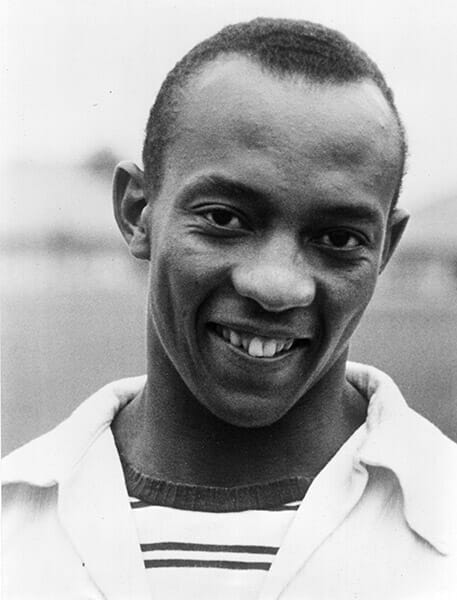

Jesse Owens (1913-1980) gained lasting fame as a track and field star in college and for his four gold medals in the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, Germany. Owens’s athletic feats, and his later public relations work in a segregated society, were a source of encouragement and inspiration to the African American struggle for recognition and equality.

Owens, Jesse

James Cleveland Owens was born on September 12, 1913, in Oakville, Lawrence County. Known to his family as J.C., he was the ninth of 10 children born to Henry and Emma Owens. Shortly after World War I, his family abandoned their sharecropping struggles in Alabama and joined many other African Americans who left the South to seek new opportunities in the North and West in what became known as the Great Migration. The family settled in Cleveland, Ohio, and initially prospered in the city’s industrial economy. Owens was enrolled in an integrated elementary school, where popular lore suggests that a teacher mistook his nickname for Jesse, instead of J.C., and the nickname stuck among his peers. The Great Depression and a car accident that crippled his father caused financial setbacks for the family. Wishing to aid his struggling family, the practical Owens enrolled at East Technical High School in 1930, believing that a vocational education would guarantee future employment.

Owens, Jesse

James Cleveland Owens was born on September 12, 1913, in Oakville, Lawrence County. Known to his family as J.C., he was the ninth of 10 children born to Henry and Emma Owens. Shortly after World War I, his family abandoned their sharecropping struggles in Alabama and joined many other African Americans who left the South to seek new opportunities in the North and West in what became known as the Great Migration. The family settled in Cleveland, Ohio, and initially prospered in the city’s industrial economy. Owens was enrolled in an integrated elementary school, where popular lore suggests that a teacher mistook his nickname for Jesse, instead of J.C., and the nickname stuck among his peers. The Great Depression and a car accident that crippled his father caused financial setbacks for the family. Wishing to aid his struggling family, the practical Owens enrolled at East Technical High School in 1930, believing that a vocational education would guarantee future employment.

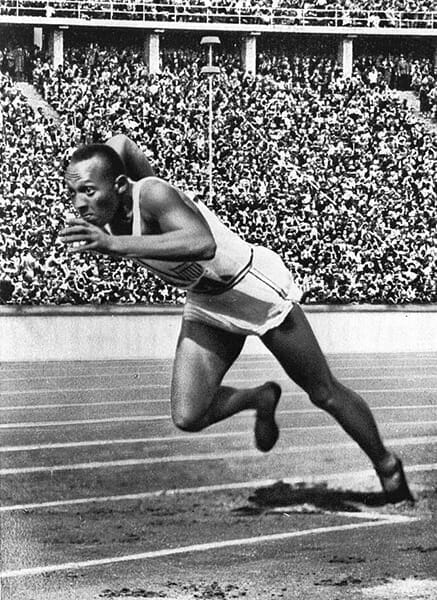

Jesse Owens at the 1936 Olympics

Owens developed into a track and field star in the sprints and long jump. He dominated interscholastic competition and by the summer of 1933 was challenging world-class sprinters in national Amateur Athletic Union meets. A host of colleges coveted his athletic talents, and Owens eventually chose to enroll at the Ohio State University (OSU). Although OSU claimed to be an integrated campus, Owens found himself barred from the dormitories and kept out of public view in his job as a freight elevator operator in the state government office complex. Adopting a stance that he maintained throughout his life, Owens did not directly confront the racial slights and focused on developing his athletic abilities. As with many African Americans of his generation, especially those who spent some time in the South, Owens rarely attacked segregation and racism head on. Unlike Jackie Robinson, who was very confrontational, Owens usually remained quiet and focused his energies in other directions. He regularly spoke out against segregation and racism in general, especially after he became famous, but his condemnations were usually broad and historical rather than aimed at specific targets. He did not join the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) or the Congress of Racial Equality, but gravitated to the much more moderate Urban League.

Jesse Owens at the 1936 Olympics

Owens developed into a track and field star in the sprints and long jump. He dominated interscholastic competition and by the summer of 1933 was challenging world-class sprinters in national Amateur Athletic Union meets. A host of colleges coveted his athletic talents, and Owens eventually chose to enroll at the Ohio State University (OSU). Although OSU claimed to be an integrated campus, Owens found himself barred from the dormitories and kept out of public view in his job as a freight elevator operator in the state government office complex. Adopting a stance that he maintained throughout his life, Owens did not directly confront the racial slights and focused on developing his athletic abilities. As with many African Americans of his generation, especially those who spent some time in the South, Owens rarely attacked segregation and racism head on. Unlike Jackie Robinson, who was very confrontational, Owens usually remained quiet and focused his energies in other directions. He regularly spoke out against segregation and racism in general, especially after he became famous, but his condemnations were usually broad and historical rather than aimed at specific targets. He did not join the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) or the Congress of Racial Equality, but gravitated to the much more moderate Urban League.

Owens became a national star during his time at OSU. In May 1935, at the Big Ten Championships in Ann Arbor, Michigan, Owens set world records in the long jump, 220-yard dash, and 220-yard low hurdles and tied the world record in the 100-yard dash, all in less than one hour. Track and field fans consider that performance the greatest in the history of the sport. Owens married Minnie Ruth Solomon in 1935, and the couple would have three daughters. As Owens entered his senior year, many people urged the United States to boycott the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin after revelations of Nazi oppression. Groups in favor of and against a boycott competed to recruit famous athletes for their cause, particularly gold-medal favorite Owens. He initially supported a boycott but then altered his position. In an era when white America paid more attention to the athletic exploits of Owens and the boxing feats of Joe Louis than to any other African American accomplishments, boycotting an immensely popular global event was not an option.

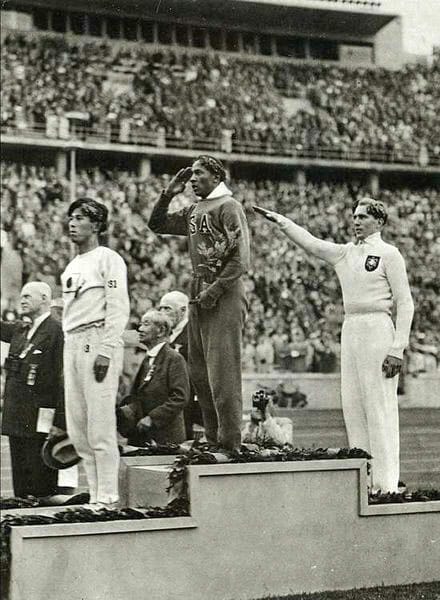

Jesse Owens Wins Gold

In Berlin, Owens dominated the Olympics. He won gold medals in the 100-meter dash, the 200-meter dash, the long jump, and the 4 x 100-meter relay, a feat that remained unequaled until fellow Alabama native Carl Lewis‘s Olympic performance in 1984. At a time when the Nazis were promoting the superiority of whites, and the Aryan race in particular, Owens helped challenge these myths of superiority. Reports of Owens’s success spread throughout the United States, as did claims that German Chancellor Adolf Hitler snubbed Owens because of his race. Owens returned to the United States a national hero but still a second-class citizen. Huge parades honored his achievements and lucrative offers sought to take advantage of his fame. Owens went back to OSU after the Olympics but never earned a degree. He lost out on several professional opportunities, including a job as head track coach at Wilberforce College because he failed to graduate. In the absence of a professional track and field circuit, Owens was unable to take advantage of his running and jumping abilities, and the Olympic Games were halted because of World War II.

Jesse Owens Wins Gold

In Berlin, Owens dominated the Olympics. He won gold medals in the 100-meter dash, the 200-meter dash, the long jump, and the 4 x 100-meter relay, a feat that remained unequaled until fellow Alabama native Carl Lewis‘s Olympic performance in 1984. At a time when the Nazis were promoting the superiority of whites, and the Aryan race in particular, Owens helped challenge these myths of superiority. Reports of Owens’s success spread throughout the United States, as did claims that German Chancellor Adolf Hitler snubbed Owens because of his race. Owens returned to the United States a national hero but still a second-class citizen. Huge parades honored his achievements and lucrative offers sought to take advantage of his fame. Owens went back to OSU after the Olympics but never earned a degree. He lost out on several professional opportunities, including a job as head track coach at Wilberforce College because he failed to graduate. In the absence of a professional track and field circuit, Owens was unable to take advantage of his running and jumping abilities, and the Olympic Games were halted because of World War II.

Pursuing the typical avenues then open to African Americans, Owens found roles in the entertainment industry that ranged from fronting a swing band to racing against horses at county fairs. Although racism certainly limited his opportunities, Owens made a good living through his entertainment pursuits. He also received substantial sums from the Republican Party to support their candidates against Democrats, who were then eager to win over African American voters who until the 1930s had supported the Republicans as the “party of emancipation.” Owens lost most of his newfound riches in unsuccessful business ventures and through spending. Fortunately, World War II marked a turning point in Owens’s post-athletic career. In 1942, he was offered a job with the federal government as a liaison to the black community for a national fitness program sponsored by the Office of Civilian Defense. In 1943, the Ford Motor Company recruited Owens away from the federal government to oversee corporate relations with black employees, and he relocated to Detroit.

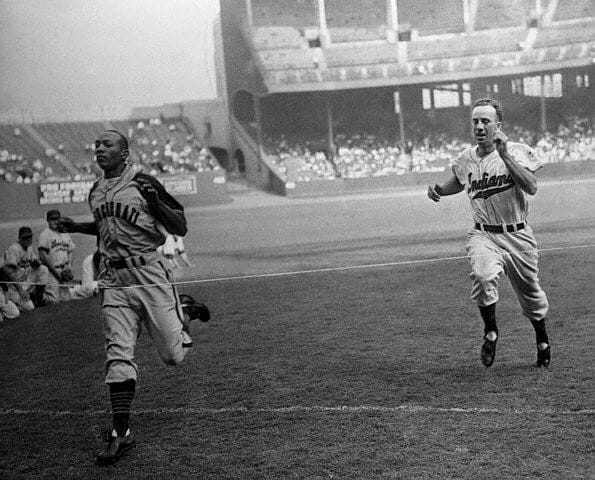

Jesse Owens and George Case

Owens’s fortunes briefly declined when World War II ended. Ford replaced Owens in a management reorganization in 1945, and a sporting goods store he opened in Detroit that same year quickly failed. Owens then went back on tour, running in theatrical races against horses and his old Olympic teammate, Helen Stephens. In 1949, he relocated to Chicago and took executive positions for several companies, including the Mutual of Omaha Insurance Corporation, the Illinois Athletic Commission, and the South Side Boys Club. He also opened several businesses, including a successful public relations agency. In 1953, the Republican governor of Illinois appointed Owens head of the Illinois Youth Commission and over the next decade Owens oversaw the state’s recreational and educational programs targeting adolescents.

Jesse Owens and George Case

Owens’s fortunes briefly declined when World War II ended. Ford replaced Owens in a management reorganization in 1945, and a sporting goods store he opened in Detroit that same year quickly failed. Owens then went back on tour, running in theatrical races against horses and his old Olympic teammate, Helen Stephens. In 1949, he relocated to Chicago and took executive positions for several companies, including the Mutual of Omaha Insurance Corporation, the Illinois Athletic Commission, and the South Side Boys Club. He also opened several businesses, including a successful public relations agency. In 1953, the Republican governor of Illinois appointed Owens head of the Illinois Youth Commission and over the next decade Owens oversaw the state’s recreational and educational programs targeting adolescents.

During the 1950s, in the midst of the Cold War with the Soviet Union, Owens reemerged as a symbol of American freedom and social mobility and offered himself as living testimony that an African American could succeed in the land of opportunity. The administration of Pres. Dwight D. Eisenhower noticed Owens’s worldwide popularity and his ease with audiences and sent the Olympic hero on international goodwill tours, which continued through the 1960s and 1970s. He also continued to support Republican politicians, such as Richard Nixon, at a time when most African Americans supported the Democratic Party. When the Democrats took power in Illinois in the election of 1960, Owens’s support for Republicans cost him his seat on the Illinois Youth Commission, and he was replaced by the new administration. Though his political opportunities had been derailed, his career as a corporate spokesperson for a variety of companies, including Quaker Oats, Sears and Roebuck, and Johnson & Johnson, flourished. Owens endorsed corporate products and also lent his credibility as a symbol of fair play and racial progress to the firms with which he partnered.

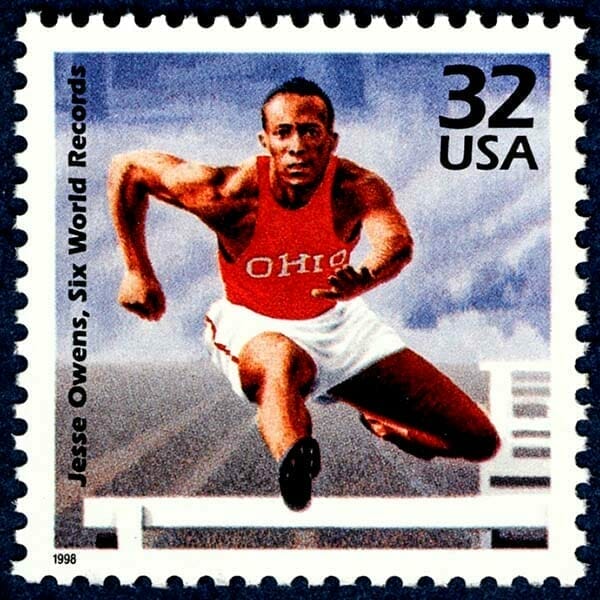

Jesse Owens Stamp

Throughout the turbulent social changes of the civil rights era, Owens was invoked by the white establishment as the one of the movement’s trailblazers. Owens espoused the message of his longtime hero, Booker T. Washington, promoting gradualism and individualism as the path toward racial equality. Regarded by a new generation of civil rights activists as racially naïve, Owens continued to endorse the promise of American egalitarianism, even leading the charge against advocates of black power who protested racism in the United States at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. During the 1960s, Owens remained a conservative Republican, rejecting the Democrats’ “Great Society” programs. While he admired Martin Luther King Jr.’s principles, he opposed King’s tactics of confrontation in the civil rights struggle. Owens had no patience with more radical elements of the struggle, condemning Muhammad Ali for refusing induction into the military and only referring to the boxer by his Christian name, Cassius Clay. He vociferously condemned the Black Power movement as out-of-touch with the “silent black majority” in a 1970 book entitled Blackthink, which was praised by the Nixon Administration and much of the white press. A few supporters in the African American community lauded Owens for his position but the vast majority, even his fellow moderates, condemned his claim that racism no longer kept blacks from achieving success in American society. Responding to the criticisms that African Americans heaped on Blackthink, in 1972 Owens offered a mild retraction in I Have Changed. He belatedly gave credit to the civil rights movement for changing the American racial landscape, reluctantly recanted his claim that all forms of activism were inherently flawed, and briefly admitted that racism fundamentally hampered access to equal opportunities. Long after the marches and protests in Selma, Birmingham, and Montgomery had remade the Alabama of his birth, Owens finally expressed admiration for the courage of those who took on segregation directly. The dismantling of legal segregation in the South was not a struggle in which he participated personally, and when he remembered the Alabama of his childhood it was as a part of his testimony about his “born again” spiritual experience rather than a reflection on the evils of Jim Crow.

Jesse Owens Stamp

Throughout the turbulent social changes of the civil rights era, Owens was invoked by the white establishment as the one of the movement’s trailblazers. Owens espoused the message of his longtime hero, Booker T. Washington, promoting gradualism and individualism as the path toward racial equality. Regarded by a new generation of civil rights activists as racially naïve, Owens continued to endorse the promise of American egalitarianism, even leading the charge against advocates of black power who protested racism in the United States at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. During the 1960s, Owens remained a conservative Republican, rejecting the Democrats’ “Great Society” programs. While he admired Martin Luther King Jr.’s principles, he opposed King’s tactics of confrontation in the civil rights struggle. Owens had no patience with more radical elements of the struggle, condemning Muhammad Ali for refusing induction into the military and only referring to the boxer by his Christian name, Cassius Clay. He vociferously condemned the Black Power movement as out-of-touch with the “silent black majority” in a 1970 book entitled Blackthink, which was praised by the Nixon Administration and much of the white press. A few supporters in the African American community lauded Owens for his position but the vast majority, even his fellow moderates, condemned his claim that racism no longer kept blacks from achieving success in American society. Responding to the criticisms that African Americans heaped on Blackthink, in 1972 Owens offered a mild retraction in I Have Changed. He belatedly gave credit to the civil rights movement for changing the American racial landscape, reluctantly recanted his claim that all forms of activism were inherently flawed, and briefly admitted that racism fundamentally hampered access to equal opportunities. Long after the marches and protests in Selma, Birmingham, and Montgomery had remade the Alabama of his birth, Owens finally expressed admiration for the courage of those who took on segregation directly. The dismantling of legal segregation in the South was not a struggle in which he participated personally, and when he remembered the Alabama of his childhood it was as a part of his testimony about his “born again” spiritual experience rather than a reflection on the evils of Jim Crow.

Jesse Owens Museum

In the last decade of his life Owens was a member of the Board of Directors of the United States Olympic Committee and enjoyed the accolades of an appreciative nation. He gave constant public lectures, retelling stories of his athletic experiences, his recipes for success, and his faith in the American dream. In the early 1970s he relocated to Arizona. On March 31, 1980, 66-year-old Jesse Owens succumbed to lung cancer in Tucson, Arizona. At a funeral attended by thousands of admirers and dignitaries, he was laid to rest in Chicago. His life and accomplishments are celebrated at the Jesse Owens Memorial Park and Museum in his birthplace of Oakville, Lawrence County. Owens is remembered as the nation’s greatest Olympian and a symbol of triumph over obstacles and achievement of the American dream of social mobility.

Jesse Owens Museum

In the last decade of his life Owens was a member of the Board of Directors of the United States Olympic Committee and enjoyed the accolades of an appreciative nation. He gave constant public lectures, retelling stories of his athletic experiences, his recipes for success, and his faith in the American dream. In the early 1970s he relocated to Arizona. On March 31, 1980, 66-year-old Jesse Owens succumbed to lung cancer in Tucson, Arizona. At a funeral attended by thousands of admirers and dignitaries, he was laid to rest in Chicago. His life and accomplishments are celebrated at the Jesse Owens Memorial Park and Museum in his birthplace of Oakville, Lawrence County. Owens is remembered as the nation’s greatest Olympian and a symbol of triumph over obstacles and achievement of the American dream of social mobility.

Additional Resources

Baker, William J. Jesse Owens: An American Life. New York: Macmillan, 1986.

Dyreson, Mark. “Jesse Owens and American Racial Mythologies.” In Out of the Shadows: A Biographical History of the African American Athlete, edited by David W. Wiggins. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2006.

Owens, Jesse, and Paul Neimark. The Jesse Owens Story. New York: Putnam’s, 1970.

———. Blackthink: My Life as Black Man and White Man. New York: William Morrow, 1970.

———. I Have Changed. New York: William Morrow, 1972.

———. Jesse: A Spiritual Journey. Plainfield, N.J.: Logos International, 1978.