Railroad Bill

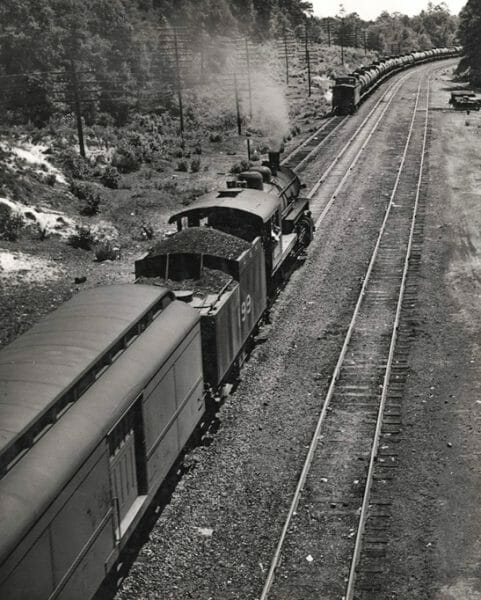

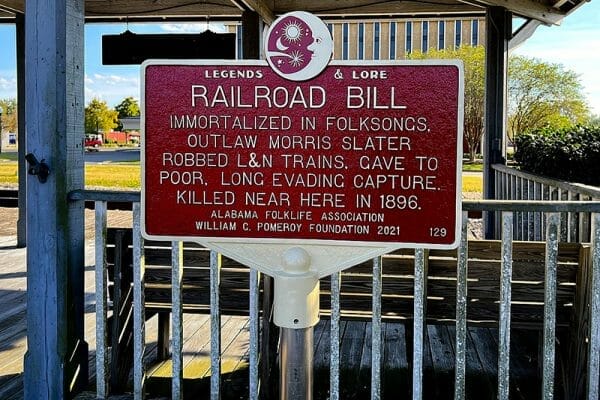

The legend of Railroad Bill arose in the winter of 1895, along the Louisville and Nashville (L&N) Railroad line in southern Alabama. Based loosely on the exploits of an African American outlaw known as “Railroad Bill,” tales of his brief but action-filled career on the wrong side of the law have been preserved in song, fiction, and theater. He has been variously portrayed as a “Robin Hood” character, a murderous criminal, a shape shifter, and a nameless victim of the Jim Crow South. He was never conclusively identified, but L&N detectives claimed he was a man named Morris Slater, and some residents of Brewton believed him to be a man called Bill McCoy who was shot by local law enforcement.

Stories about Railroad Bill began to surface in early 1895, when an armed vagrant began riding the L&N boxcars between Flomaton and Mobile. He earned the nickname “Railroad Bill,” or sometimes just “Railroad,” from the trainmen who had trouble detaining the rifle-wielding hitchhiker. On March 6, 1895, railroad employees attempted to restrain a man they found sleeping on a water tank along the railroad. The man fired on them and escaped into the woods after hijacking a train car. This incident sparked a manhunt by railroad company detectives that led a posse to Bay Minette on April 6, 1895. When detectives confronted an armed man there, he killed Baldwin County deputy sheriff James H. Stewart in the ensuing gunfight and evaded capture again.

The deputy’s killing swung the full attention of law enforcement and the media toward Railroad Bill. A notice for a $500 reward posted in Mobile identified him as Morris Slater, a convict-lease worker who in 1893 had fled from a turpentine camp in Bluff Springs, Florida, after killing a lawman. Slater had been nicknamed “Railroad Time” for his rapid work pace. Railroad Bill crossed into Florida where, on July 4, 1895, Brewton sheriff E. S. McMillan tracked him to a house near Bluff Springs. As the sheriff approached the dwelling, the fugitive opened fire and disappeared into the woods, leaving McMillan fatally wounded.

The killing of McMillan marked a turning point and greatly expanded the efforts in both Alabama and Florida to hunt Railroad Bill down. Despite the increase in manpower, the outlaw remained at large, robbing trains and reportedly selling goods to impoverished people for prices lower than the local merchant stores, as well as engaging in occasional shoot-outs with lawmen and L&N authorities. All the while, his legend grew, especially in Alabama’s African American community. Although the majority of Black citizens condemned Railroad Bill’s actions, many also admired his courage and audacity. Some people attributed supernatural powers to him, maintaining that he was able to evade capture by changing into animal form and was only vulnerable to silver bullets. Other tales said that he had the power to disable the tracking abilities of the bloodhounds on his trail. One such tale, recounted by Carl Carmer in The Hurricane’s Children: Tales from Your Neck o’ the Woods, describes a lawman chasing Railroad Bill:

So the sheriff decided Railroad Bill must be hiding under the low bushes in the clearing and he began looking around. Pretty soon he started a little red fox that lit out through the woods. The sheriff let go with both barrels of his shotgun, but he missed. After the second shot the little red fox turned about and laughed at him a high, wild, hearty laugh—and the sheriff recognized it. That little fox was Railroad Bill.

By the summer of 1895, the L&N Railroad, the state of Alabama, the state of Florida, the town of Brewton, and Escambia County had pooled together a reward of $1,250 for Railroad Bill’s capture. A host of bounty hunters from places as far away as Texas and Indiana descended on southwestern Alabama and the western swamps of Florida. They were joined by operatives of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, L&N detectives, lawmen, and vigilante posses.

Many innocent African Americans soon found themselves paying heavily for Railroad Bill’s crimes, as questionably identified suspects were brought in for the reward, or were accused of being accomplices. Some of the men arrested suffered beatings or whippings, and others were murdered. On July 16, the Pine Belt News in Brewton ran a headline that stated “The Wrong Man Shot,” and other reports from Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, and Texas filtered in about men killed after being misidentified as Railroad Bill. By August 2, the Montgomery Daily Advertiser was reporting that those hunting the fugitive had become a “small army” numbering “at least one hundred men here loaded for bear.”

The hunt for Railroad Bill persisted until March 7, 1896, when a man was gunned down by a host of law enforcement officials at Tidmore and Ward’s General Store in Atmore, a depot town along the L&N. Accounts of the final episode in Railroad Bill’s bloody career widely differ. Some say that authorities surprised and killed the man as he sat on an oak barrel eating cheese and crackers. Other accounts say that he engaged the lawmen in a shoot-out in front of the store, and still others contend that he walked into a trap at Tidmore and Ward’s.

Railroad Bill’s body was placed on public view in Brewton, and crowds of curious spectators gathered to get a glimpse. Many Brewton residents recognized the man as Bill McCoy, a local troublemaker who had threatened local saw-mill owner T. R. Miller with a knife at around the same time Morris Slater was working in the turpentine camp in Florida. Souvenir hunters paid 50 cents for a picture of Constable J. L. McGowan, believed to have fired the fatal shot, standing, rifle in hand, over the corpse of Railroad Bill strapped to a wooden plank. After a few days in Brewton, the body was taken by train to Montgomery and later to Pensacola, Florida, for public display. So many people came to see Railroad Bill in Montgomery that authorities charged an admission fee of 25 cents. His body’s final resting place is unknown.

Railroad Bill was a symbol of the racial and economic divide in the post-Reconstruction Deep South. During this period of increasing legal segregation in Alabama and the rest of the South, the hunt for Railroad Bill became a theatrical white supremacist saga in local newspapers. The outlaw’s legacy has been passed down through generations in many cultural representations. Railroad Bill blues ballads began circulating in the early twentieth century; one was recorded by Riley Puckett and Gid Tanner in 1924. Musicologist Alan Lomax recorded a version of Railroad Bill by Payneville native Vera Ward Hall in 1939. Blues singers have used “Railroad Bill” as a stage name, and the popularity of the ballads exploded during the folk revival of the 1950s and 60s. In 1981, the Labor Theater in New York City produced the musical play Railroad Bill by C. R. Portz.

Further Reading

- Mathews, Burgin. “‘Looking for Railroad Bill’: On the Trail of an Alabama Badman.” Southern Cultures 2003 9(3): 66-88.

- Penick, James. “Railroad Bill.” Gulf Coast Historical Review 1194 10(1): 85-92.

- Roberts, John W. “‘Railroad Bill’ and the American Outlaw Tradition.” Western Folklore 1981 40(4): 315-28.