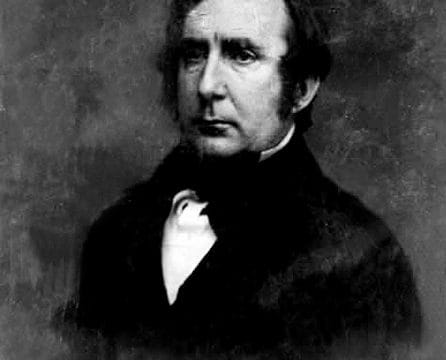

Frank M. Johnson Jr.

Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr.

As a federal judge, Frank M. Johnson Jr. (1918-1999) played a crucial role in shaping civil-rights law in America and applying it in Alabama. Civil-rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. once called him “the man who gave true meaning to the word justice.” Johnson’s legal decisions desegregated schools in Alabama, busing in Montgomery, eliminated the state poll tax, allowed blacks to serve on juries, and authorized the 1965 civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery. Many other rulings also had far-reaching consequences toward achieving civil rights for blacks, inmates, and the mentally ill.

Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr.

As a federal judge, Frank M. Johnson Jr. (1918-1999) played a crucial role in shaping civil-rights law in America and applying it in Alabama. Civil-rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. once called him “the man who gave true meaning to the word justice.” Johnson’s legal decisions desegregated schools in Alabama, busing in Montgomery, eliminated the state poll tax, allowed blacks to serve on juries, and authorized the 1965 civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery. Many other rulings also had far-reaching consequences toward achieving civil rights for blacks, inmates, and the mentally ill.

Frank Minis Johnson Jr. was born on October 30, 1918, in Haleyville and grew up in hilly Winston County. With few slaves and little cotton production, the county became a Unionist stronghold during the Civil War. More than twice as many men from Winston served in the U.S. Army as in the Confederate Army, including two of Johnson’s great uncles. After the war, the county joined others in similar rugged regions of Georgia, Virginia, Tennessee, and North Carolina in what became known as “mountain Republican” strongholds. Johnson’s great-grandfather was elected sheriff as a Republican, and his father was elected in 1942 as the only Republican in the Alabama legislature after serving many years as the elected Republican probate judge in Winston County.

Johnson’s father married Alabama Sivilla Long, whose father had moved from Pennsylvania to operate a coal mine in Alabama. Frank Jr., the first of seven children, had three brothers and three sisters. He attended the public schools in Haleyville and Double Springs before enrolling for his senior year at Gulf Coast Military Academy in Gulfport, Mississippi. Frank Jr. decided to become a lawyer after watching trials at the county courthouse where his father worked. He later attended Republican national conventions with his father, where he met such men as Herbert Brownell, who later served as Dwight Eisenhower’s 1952 presidential campaign manager and attorney general, as well as future chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court Warren Burger.

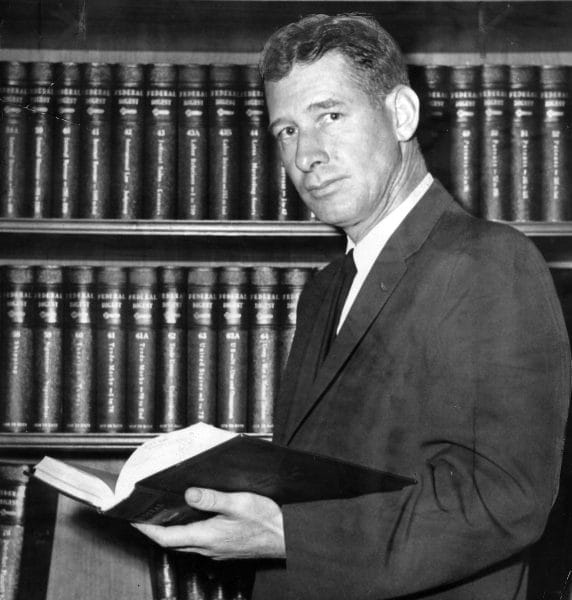

Frank M. Johnson

At age 19 Johnson married 18-year-old Ruth Jenkins on January 16, 1938. Both enrolled the next year at the University of Alabama, and in 1943, he graduated near the top of his law class. While in law school, Johnson befriended future Alabama governor George C. Wallace, with whom he would spar over school desegregation. Gov. Wallace years later acknowledged that he was “wrong” on that issue and that Judge Johnson was “right.” Johnson enlisted in the army in 1943 and served as a combat infantry lieutenant in Europe in World War II, where he twice received the Purple Heart for combat wounds and the Bronze Star “for exemplary conduct in ground combat against the enemy.” He attracted press attention when he served as defense counsel for enlisted men who had brutalized soldiers who were away without official leave (AWOL) and implicated higher-ups. After a major general testified he only looked into the “administrative status” of previous investigations, Johnson cited an order from Gen. Dwight Eisenhower to investigate charges of brutality. He accused the major general of virtually admitting that he had failed to carry out his duties. Johnson also demonstrated that the commanding colonel at the Litchfield prison had directed subordinates to order guards to beat disruptive prisoners.

Frank M. Johnson

At age 19 Johnson married 18-year-old Ruth Jenkins on January 16, 1938. Both enrolled the next year at the University of Alabama, and in 1943, he graduated near the top of his law class. While in law school, Johnson befriended future Alabama governor George C. Wallace, with whom he would spar over school desegregation. Gov. Wallace years later acknowledged that he was “wrong” on that issue and that Judge Johnson was “right.” Johnson enlisted in the army in 1943 and served as a combat infantry lieutenant in Europe in World War II, where he twice received the Purple Heart for combat wounds and the Bronze Star “for exemplary conduct in ground combat against the enemy.” He attracted press attention when he served as defense counsel for enlisted men who had brutalized soldiers who were away without official leave (AWOL) and implicated higher-ups. After a major general testified he only looked into the “administrative status” of previous investigations, Johnson cited an order from Gen. Dwight Eisenhower to investigate charges of brutality. He accused the major general of virtually admitting that he had failed to carry out his duties. Johnson also demonstrated that the commanding colonel at the Litchfield prison had directed subordinates to order guards to beat disruptive prisoners.

That penchant for speaking truth to power would be recurrent in Johnson’s later career. He was discharged from the army as a captain in 1946, and he and Ruth settled in Jasper, where Johnson joined the law firm of Curtis & Maddox. The couple also adopted an infant boy, their only child, who they named James Curtis.

Bill Baxley, Frank Johnson, Jim Folsom Sr.

In 1952, Johnson headed up “Veterans for Eisenhower,” Eisenhower’s presidential campaign effort in Alabama. He was appointed U.S. attorney for the state’s Northern District by Attorney General Herbert Brownell, who took special note of the fact that Johnson won, in May 1954, the only conviction ever in Alabama for peonage, in which a person forces a debtor to work in slave-like conditions to pay off the debt. When the federal judge for Alabama’s Middle District died unexpectedly, Eisenhower named Johnson to succeed him. Johnson moved to Montgomery and took the oath in October 1955, just before his 37th birthday, making him the youngest federal judge in the country.

Bill Baxley, Frank Johnson, Jim Folsom Sr.

In 1952, Johnson headed up “Veterans for Eisenhower,” Eisenhower’s presidential campaign effort in Alabama. He was appointed U.S. attorney for the state’s Northern District by Attorney General Herbert Brownell, who took special note of the fact that Johnson won, in May 1954, the only conviction ever in Alabama for peonage, in which a person forces a debtor to work in slave-like conditions to pay off the debt. When the federal judge for Alabama’s Middle District died unexpectedly, Eisenhower named Johnson to succeed him. Johnson moved to Montgomery and took the oath in October 1955, just before his 37th birthday, making him the youngest federal judge in the country.

Six weeks later, Rosa Parks refused to surrender her seat on a Montgomery bus to a white passenger, which led directly to a bus boycott by blacks in protest of segregated seating. While Parks’s case was tied up in state courts, Amelia Browder was listed first among four black plaintiffs in the federal lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the state’s segregation law, known as Browder v. Gayle. When the case was filed in his court, Johnson called for a special three-judge district court to consider the constitutional challenge. When the judges met after the trial to decide the case, Johnson later recalled, he told the presiding judge, Richard T. Rives of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, that the law was clear and does not tolerate discrimination on the basis of race. Segregation in any public facility is unconstitutional and violates the equal-protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, Johnson explained. Judge Rives agreed in a 2-1 decision that the U.S. Supreme Court later upheld.

Browder v. Gayle set the trail-blazing direction Johnson would follow for 24 years as the presiding judge in some of the nation’s most important and far-reaching civil-rights cases. Johnson issued the nation’s first statewide school desegregation order in the 1963 case Lee v. Macon County Board of Education. Later rulings struck down barriers to voting and serving on juries, whereas others extended constitutional protection to abused prison inmates and mental patients. He broke new ground in desegregating the Alabama highway patrol and ruling on gender discrimination. The trooper case over time provided for nondiscriminatory recruiting, testing, training, and promotion policies. In a pioneering case of gender discrimination, Johnson’s dissenting opinion on a three-judge district court called for the Air Force to provide spousal education benefits to the husband of a female officer equal to those for the wife of a male officer. The Supreme Court adopted his position.

Selma to Montgomery March End

When Alabama state troopers and a sheriff’s posse assaulted civil-rights marchers protesting voter discrimination in Selma and Dallas County on March 7, 1965, Johnson ordered that the Selma-to-Montgomery march be allowed to take place, creating the climate for passage of that year’s landmark Voting Rights Act. His ruling set precedent by applying the traditional legal principle of proportionality to constitutional injury. As he explained the case, “It seems basic to our constitutional principles that the extent of the right to assemble, demonstrate and march peaceably along the highways and streets in an orderly manner should be commensurate with the enormity of the wrongs that are being protested and petitioned against. In this case, the wrongs are enormous.” He issued the order only after getting the assurance of Pres. Lyndon Johnson that it would be enforced. Because of the controversy surrounding the cases and intense opposition to change, federal marshals provided him round-the-clock protection for almost 15 years, beginning after a cross was burned on his front lawn in December 1956 following the Supreme Court’s final order to desegregate the buses in Montgomery. Without complaint, he endured social ostracism, death threats, and the bombing of his mother’s home in the mistaken belief that the home was his.

Selma to Montgomery March End

When Alabama state troopers and a sheriff’s posse assaulted civil-rights marchers protesting voter discrimination in Selma and Dallas County on March 7, 1965, Johnson ordered that the Selma-to-Montgomery march be allowed to take place, creating the climate for passage of that year’s landmark Voting Rights Act. His ruling set precedent by applying the traditional legal principle of proportionality to constitutional injury. As he explained the case, “It seems basic to our constitutional principles that the extent of the right to assemble, demonstrate and march peaceably along the highways and streets in an orderly manner should be commensurate with the enormity of the wrongs that are being protested and petitioned against. In this case, the wrongs are enormous.” He issued the order only after getting the assurance of Pres. Lyndon Johnson that it would be enforced. Because of the controversy surrounding the cases and intense opposition to change, federal marshals provided him round-the-clock protection for almost 15 years, beginning after a cross was burned on his front lawn in December 1956 following the Supreme Court’s final order to desegregate the buses in Montgomery. Without complaint, he endured social ostracism, death threats, and the bombing of his mother’s home in the mistaken belief that the home was his.

The Republican “Southern strategy”—a shift away from support of civil rights aimed at appealing to conservative white voters that began with Barry Goldwater’s 1964 campaign for president—kept Johnson off the Supreme Court despite Chief Justice Burger telling him that Pres. Richard Nixon was about to nominate him to succeed fellow Alabamian Justice Hugo Black. A contrite congressman, William Dickinson, years later told Johnson how he and two fellow Alabama House Republicans blocked him by complaining to Attorney General John Mitchell that such an appointment would hurt them politically. Pres. Jimmy Carter nominated Johnson to become director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1977, but Johnson withdrew after a slow recovery from heart surgery.

Frank M. Johnson Jr. Federal Building and Courthouse

In 1979, Carter appointed Johnson to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, where he joined fellow progressive judge Robert Smith Vance and quickly played a major role in resolving a long-time issue of splitting off three of the six states—Alabama, Florida, and Georgia—as the new Eleventh Circuit, headquartered in Atlanta. He served 20 years on the Eleventh Circuit, maintaining his judicial chambers in Montgomery. He helped decide a number of cases that broke new legal ground. In Doe v. Plyler, for example, the Supreme Court upheld his opinion that a public school district could not impose tuition of $1,000 for children of illegal aliens. Such plaintiff children “have committed no moral wrong” in being under the control of their parents, he observed, and to suggest that they “are being excluded from education for their own illegal actions places form over substance.”

Frank M. Johnson Jr. Federal Building and Courthouse

In 1979, Carter appointed Johnson to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, where he joined fellow progressive judge Robert Smith Vance and quickly played a major role in resolving a long-time issue of splitting off three of the six states—Alabama, Florida, and Georgia—as the new Eleventh Circuit, headquartered in Atlanta. He served 20 years on the Eleventh Circuit, maintaining his judicial chambers in Montgomery. He helped decide a number of cases that broke new legal ground. In Doe v. Plyler, for example, the Supreme Court upheld his opinion that a public school district could not impose tuition of $1,000 for children of illegal aliens. Such plaintiff children “have committed no moral wrong” in being under the control of their parents, he observed, and to suggest that they “are being excluded from education for their own illegal actions places form over substance.”

Pres. Bill Clinton awarded Johnson a Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1995 for landmark decisions in the areas of desegregation, voting rights, and civil liberties, and Congress in 1992 named the federal courthouse in Montgomery for Johnson. The Alabama legislature, 25 years after calling for his impeachment by Congress, passed a resolution honoring him. Judge Frank Johnson Jr. died on July 23, 1999, in Montgomery after a period of declining health and was buried in his native Winston County. In 2019, a group of people who admired Johnson’s life and work created the Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. Institute in Montgomery as a non-partisan effort to promote knowledge of the U.S. Constitution and the federal judiciary and to promote civil discourse.

Further Reading

- Bass, Jack. Taming the Storm: The Life and Times of Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr., and the South’s Fight over Civil Rights. New York: Doubleday, 1993.

- Kennedy, Robert F., Jr. Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr.: A Biography. New York: Putnam, 1978.

- Sikora, Frank. The Judge: The Life and Opinions of Alabama’s Frank M. Johnson, Jr. Montgomery, Ala.: Black Belt Press, 1992.

- Yarbrough, Tinsley E. Judge Frank Johnson and Human Rights in Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1981.