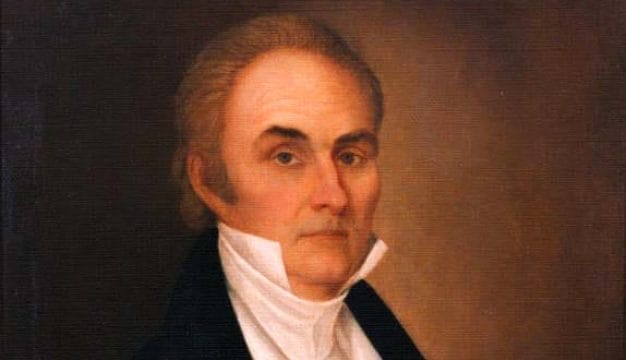

Horace King

Horace King

Horace King (1807-1885) was the most respected bridge-builder in Alabama, Georgia, and northeastern Mississippi during the mid-nineteenth century. Enslaved until 1846, King and his owner, John Godwin, worked as partners on major construction projects. By 1860, he was one of the wealthiest free blacks in Alabama. Both in slavery and a free black, King traveled without any restrictions throughout the Deep South. After reluctantly working for the Confederacy, he served as an Alabama legislator during Reconstruction. His role as an engineer and contractor, during a period when few professional opportunities existed for African Americans, earned him a legendary status that was enhanced over time by towns eager to claim, sometimes erroneously, their own Horace King covered bridge, warehouse, mill, courthouse, church, elaborate Gothic house, or staircase. After his death, local historians and journalists frequently cited Horace King as an example of a successful African American. Although he certainly was an exceptional bridge architect and builder of massive heavy-timber frame structures, his career as an entrepreneur was limited by the racial biases of his time.

Horace King

Horace King (1807-1885) was the most respected bridge-builder in Alabama, Georgia, and northeastern Mississippi during the mid-nineteenth century. Enslaved until 1846, King and his owner, John Godwin, worked as partners on major construction projects. By 1860, he was one of the wealthiest free blacks in Alabama. Both in slavery and a free black, King traveled without any restrictions throughout the Deep South. After reluctantly working for the Confederacy, he served as an Alabama legislator during Reconstruction. His role as an engineer and contractor, during a period when few professional opportunities existed for African Americans, earned him a legendary status that was enhanced over time by towns eager to claim, sometimes erroneously, their own Horace King covered bridge, warehouse, mill, courthouse, church, elaborate Gothic house, or staircase. After his death, local historians and journalists frequently cited Horace King as an example of a successful African American. Although he certainly was an exceptional bridge architect and builder of massive heavy-timber frame structures, his career as an entrepreneur was limited by the racial biases of his time.

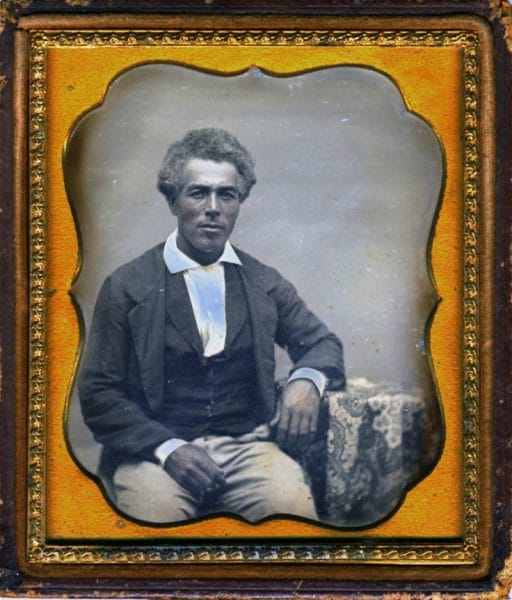

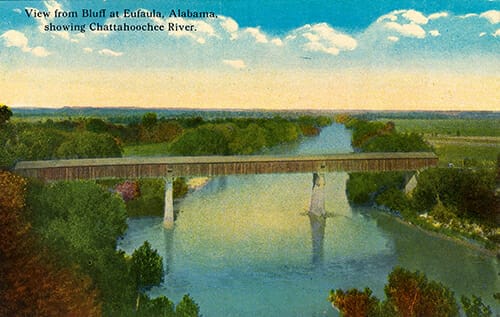

Eufaula Bridge

Born in 1807 into slavery in the Chesterfield District of South Carolina, Horace King was of mixed African, European, and Catawba ancestry. He was purchased by John Godwin, a contractor in Cheraw, South Carolina, in 1830 and may have been related to the family of Godwin’s wife, Ann Wright (1808-1854) of Marlboro, South Carolina. In 1832, the Godwins, along with Horace, his mother, brother, and sister, relocated to Girard (present-day Phenix City), Alabama, across the river from Columbus, Georgia, and the town hired Godwin to construct the first bridge across the lower Chattahoochee River. By 1837, John Godwin had transferred the ownership of the King family to his wife Ann Godwin and her uncle and financial guardian, William Carney Wright of Montgomery. This was perhaps done to prevent King from being seized by John Godwin’s creditors. In 1839, King married Frances Gould Thomas, a free Black woman who was also of mixed ancestry. Her legal status guaranteed freedom for their children.

Eufaula Bridge

Born in 1807 into slavery in the Chesterfield District of South Carolina, Horace King was of mixed African, European, and Catawba ancestry. He was purchased by John Godwin, a contractor in Cheraw, South Carolina, in 1830 and may have been related to the family of Godwin’s wife, Ann Wright (1808-1854) of Marlboro, South Carolina. In 1832, the Godwins, along with Horace, his mother, brother, and sister, relocated to Girard (present-day Phenix City), Alabama, across the river from Columbus, Georgia, and the town hired Godwin to construct the first bridge across the lower Chattahoochee River. By 1837, John Godwin had transferred the ownership of the King family to his wife Ann Godwin and her uncle and financial guardian, William Carney Wright of Montgomery. This was perhaps done to prevent King from being seized by John Godwin’s creditors. In 1839, King married Frances Gould Thomas, a free Black woman who was also of mixed ancestry. Her legal status guaranteed freedom for their children.

The unusual sanction of such a marriage by Ann Godwin and William Wright underscores the social latitude afforded the enslaved King because of his exceptional talents. Building a covered bridge required many skills, including erecting tall rock or timber piers and constructing lattice framework (trusses) of sawn lumber for the sides connected to massive hand-hewn support timbers. Builders also needed to join all the elements with treenails (large wooden pegs) and ensure that the bridge truss formed a slight arc, known as camber. Godwin probably taught King these skills, but the pupil quickly became more skilled than the teacher. Between 1838 and 1840, King supervised construction of Godwin’s massive toll bridges across the Chattahoochee River at West Point, Eufaula, and Florence (present-day Florence Marina), Georgia. Financed by private investors, each span cost close to $22,000—an indication of the economic potential of toll bridges.

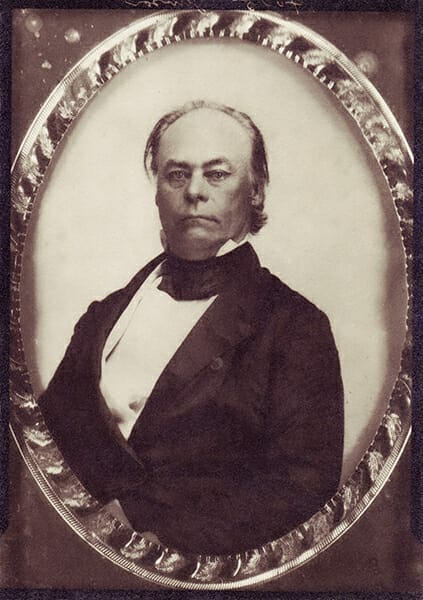

Robert Jemison Jr.

During the early 1840s, King designed and constructed bridges in Alabama and Mississippi while Godwin remained in Girard. Tuscaloosa resident Seth King (no relation to Horace), rather than Horace King, built the initial bridge in 1834 across the Black Warrior River in that town. Seth King, along with Robert Jemison Jr., a state legislator and Tuscaloosa entrepreneur, invested in Horace’s bridges at Columbus, Mississippi, in 1843 and Wetumpka, Alabama, in 1844. Godwin negotiated Horace’s fee with these investors, but Horace designed the bridges and supervised their construction. Historians believe that Godwin and Horace King probably shared the revenue. The investors made money by collecting tolls on these bridges. Jemison and Horace King continued to collaborate and developed a close working relationship. In early 1845, while working for William Carney Wright, King bridged the Tallapoosa River at Tallassee. Later that year King oversaw construction of three small bridges for Jemison near Steens, Mississippi, where Jemison owned saw and grist mills.

Robert Jemison Jr.

During the early 1840s, King designed and constructed bridges in Alabama and Mississippi while Godwin remained in Girard. Tuscaloosa resident Seth King (no relation to Horace), rather than Horace King, built the initial bridge in 1834 across the Black Warrior River in that town. Seth King, along with Robert Jemison Jr., a state legislator and Tuscaloosa entrepreneur, invested in Horace’s bridges at Columbus, Mississippi, in 1843 and Wetumpka, Alabama, in 1844. Godwin negotiated Horace’s fee with these investors, but Horace designed the bridges and supervised their construction. Historians believe that Godwin and Horace King probably shared the revenue. The investors made money by collecting tolls on these bridges. Jemison and Horace King continued to collaborate and developed a close working relationship. In early 1845, while working for William Carney Wright, King bridged the Tallapoosa River at Tallassee. Later that year King oversaw construction of three small bridges for Jemison near Steens, Mississippi, where Jemison owned saw and grist mills.

In February 1846, Jemison guided an emancipation bill for King through the Alabama legislature, and the Godwins and Wright freed him. King later asserted that he bought his freedom, possibly with income from his projects with Wright and Jemison. Whatever the factors of King’s emancipation, he and Godwin experienced a unique relationship. After Godwin’s death in 1859, King erected a monument over Godwin’s grave.

During the early 1850s, the state of Alabama hired King to perform carpentry work, including elegant circular staircases, on the new capitol building in Montgomery. In the mid-1850s King built Moore’s Bridge, over the Chattahoochee River on the road between Newnan and Carrollton, Georgia. In 1857, Milledgeville residents hired King to bridge the Oconee River at Milledgeville, Georgia’s capital at the time. King’s crews just had begun cutting timbers when a conflict arose between King and the investors. At the same time, Nelson Tift, an entrepreneur, newspaper owner, and legislator, contracted with King for a span across the Flint River at Albany, a town founded by Tift in the 1830s. According to local historians King quit the Milledgeville venture, loaded his timbers on a railroad car, and shipped them to Albany.

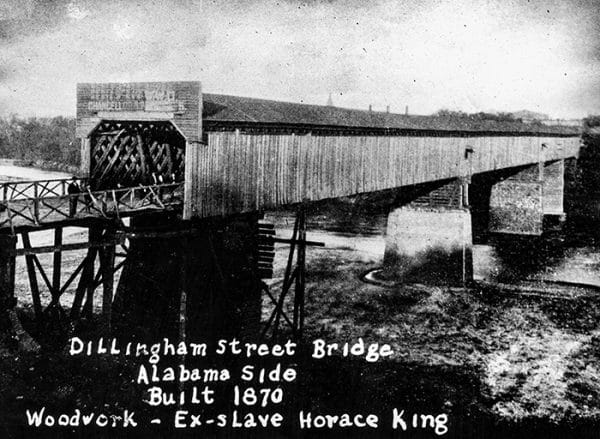

Dillingham Street Covered Bridge

By 1858, King and his family had moved to Moore’s Bridge. During the next few years, King’s activities contradict the idea of free blacks being restricted in terms of their mobility. He constructed bridges and large timber-frame buildings in Alabama and Georgia and often rode the train between his two houses at Moore’s Bridge and Girard. King’s wife Frances and their children collected tolls and farmed at Moore’s Bridge until July 1864, when Union cavalry under Gen. George Stoneman Jr. burned the span. Frances died in Girard about three months later, and in June 1865 King married Sarah Jane Jones McManus.

Dillingham Street Covered Bridge

By 1858, King and his family had moved to Moore’s Bridge. During the next few years, King’s activities contradict the idea of free blacks being restricted in terms of their mobility. He constructed bridges and large timber-frame buildings in Alabama and Georgia and often rode the train between his two houses at Moore’s Bridge and Girard. King’s wife Frances and their children collected tolls and farmed at Moore’s Bridge until July 1864, when Union cavalry under Gen. George Stoneman Jr. burned the span. Frances died in Girard about three months later, and in June 1865 King married Sarah Jane Jones McManus.

During the Civil War, King attempted to continue building bridges as an independent contractor, but necessity forced him into war-related work. After the war, King maintained that he had always been a Unionist, and that he always “begged and talked for the Union.” Even so, Confederate officials in Columbus forced the pro-Union King to blockade the lower Apalachicola River to prevent Union navigation, and the Alabama governor pressed him into the same activity along the lower Alabama River. King also erected a large mill structure and supplied wood products for Confederate naval facilities in Columbus. King maintained good relations with local naval officers, but in 1864 he wrote Jemison, then a member of the Confederate Senate, asking what would happen if he stopped working for the Confederacy. Jemison’s response, if any, has not been preserved.

Wetumpka Bridge ca. 1880s

During Reconstruction, King became a nominal, moderate Republican, serving twice as a member of the Alabama House of Representatives from 1870 to 1874. He rarely, if ever, occupied his seat during the initial year of his first term and played a limited role in later sessions. He was pre-occupied with the physical reconstruction of wagon and railroad bridges, grist and textile mills, and cotton warehouses. He had also built the initial Lee County courthouse in Opelika in 1867.

Wetumpka Bridge ca. 1880s

During Reconstruction, King became a nominal, moderate Republican, serving twice as a member of the Alabama House of Representatives from 1870 to 1874. He rarely, if ever, occupied his seat during the initial year of his first term and played a limited role in later sessions. He was pre-occupied with the physical reconstruction of wagon and railroad bridges, grist and textile mills, and cotton warehouses. He had also built the initial Lee County courthouse in Opelika in 1867.

King reportedly had financial problems but historians have not determined the circumstances. In 1872, King and his family moved to LaGrange, Georgia, where he and his sons continued to build bridges, stores, houses, and college buildings until Horace’s death, on May 28, 1885. Lengthy obituaries in white-owned Atlanta, LaGrange, and Columbus newspapers reveal the extent of his fame. King’s children—Washington W. (1843-1910), Marshall Ney (1844-79), John Thomas (1846-1926), Annie Elizabeth (1848-1919), and George (1850-1899)—continued their father’s profession. Washington moved to Atlanta and built bridges throughout Georgia; his spans, now greatly modified, can be seen at Stone Mountain and Watson Mill State Park near Comer, Georgia. Other members of the family became prominent in the black middle class of LaGrange. Both John and George were builders, and John owned a lumberyard and George operated an annual African American fair. John was the leading layman in the local Methodist Episcopal Church and served as a trustee for that denomination’s Clark University from the 1890s to the 1920s. His reputation as a builder extended into Atlanta, where he served as one of two contractors who built the Negro Building at the Atlanta Exposition in 1895. In February 2017, the Alabama state government unveiled a portrait of King in the State Capitol that he had helped to build; it is the first portrait of an African American to hang in the seat of the Alabama government.

Further Reading

- Cherry, Rev. Francis. “History of Opelika . . .” 1883. Reprint, Alabama Historical Quarterly 14 (1953): 193-97.

- Lupold, John S., and Thomas L. French Jr. Bridging Deep South Rivers: The Life and Legend of Horace King. Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 2004.

- Robert Jemison Jr. Papers, 1797-1898, W. S. Hoole Special Collections Library, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama.