John Williams Walker

Alabama Constitution Hall Replica

Few persons have played a more significant role in early Alabama history than John Williams Walker (1783-1823). A Virginia native, Walker was one of a group of entrepreneurs and politicians, known as the Broad River Group, who helped to shape the political structure of Alabama during its transition from territory to state. He promoted the development of the state economy and transportation system and although he died at 40, Walker’s role in the evolution of Alabama as a territory and a state and passage of the Land Law of 1821 significantly influenced the direction of Alabama history.

Alabama Constitution Hall Replica

Few persons have played a more significant role in early Alabama history than John Williams Walker (1783-1823). A Virginia native, Walker was one of a group of entrepreneurs and politicians, known as the Broad River Group, who helped to shape the political structure of Alabama during its transition from territory to state. He promoted the development of the state economy and transportation system and although he died at 40, Walker’s role in the evolution of Alabama as a territory and a state and passage of the Land Law of 1821 significantly influenced the direction of Alabama history.

John Williams Walker was born on April 12, 1783. His family was of Scots-Irish origin, and his paternal grandfather, William Walker, migrated to Maryland in 1740 and moved to North Carolina’s Bertie District in 1743. Walker’s father, Jeremiah Walker, was a Baptist preacher, and his mother was Mary Jane Graves Walker. In 1769, he began a 15-year pastorate in Amelia County, Virginia, and founded some 20 churches south of the James River. In 1783, soon after John’s birth, Jeremiah Walker was among several Amelia county residents who migrated to Wilkes County, Georgia, and settled at the confluence of the Broad and Savannah Rivers north of present-day Augusta.

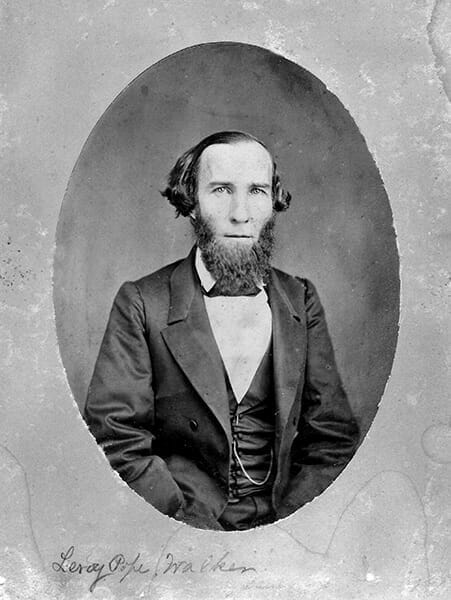

LeRoy Pope Walker

John Williams Walker’s parents both died in the early 1790s, and he then was cared for by his four brothers. He attended the Academies of Moses Waddell, across the Savannah River in Vienna, South Carolina, and in spring 1805, he entered Princeton University in New Jersey. He became ill soon after, probably with tuberculosis, and remained sickly from that time on. He graduated with distinction in the fall of 1806 and spent the winter in Washington, D.C. After returning briefly to Georgia, he joined his friend Thomas Percy near Natchez, Mississippi.

LeRoy Pope Walker

John Williams Walker’s parents both died in the early 1790s, and he then was cared for by his four brothers. He attended the Academies of Moses Waddell, across the Savannah River in Vienna, South Carolina, and in spring 1805, he entered Princeton University in New Jersey. He became ill soon after, probably with tuberculosis, and remained sickly from that time on. He graduated with distinction in the fall of 1806 and spent the winter in Washington, D.C. After returning briefly to Georgia, he joined his friend Thomas Percy near Natchez, Mississippi.

When the federal government offered former Creek Nation land in the newly established Madison County, Mississippi Territory, for sale in 1809, Walker and six other Broad River compatriots purchased almost half of the tract at the average price of two dollars an acre. In 1810, he married Matilda Pope, the daughter of the wealthy Col. LeRoy Pope, with whom he had six children, including future politicians Percy Walker and LeRoy Pope Walker. That same year the couple moved with fellow former Georgian neighbors to Madison County which encompassed the land in the “Great Bend” of the Tennessee River as well as the future site of Huntsville. By 1822, Walker had added 1,760 more acres to his land holdings. The area that became Huntsville, known at the time as Twickenham, had between two and three hundred settlers when it was sold in 1810. It was renamed Huntsville in 1811.

Walker read law and was licensed to practice by Madison County’s first Superior Court of Law and Equity in the fall of 1810. When the statehood discussions began regarding Mississippi Territory, Walker and many others in the eastern region vigorously opposed its admission as a single state. Some proposed division along a north-south line, which ultimately won out, but Walker proposed division by an east-west line. Such a division would have placed the Natchez and south Alabama regions in one state and given Madison County and north Alabama clear dominance in the other. His position endeared him to others in his region of the territory. In February 1818 he was elected to the Territorial Legislature and served on the Ways and Means Committee. Despite opposition from Gov. William Wyatt Bibb, the pro-business Walker was influential in granting the Planters and Merchants Bank of Huntsville the right to issue notes acceptable by the territory at face value. He also aided in amending the act against usury that permitted any interest rate expressed in writing. In November, he was elected to the final session of the Territorial Legislature and served as its speaker. When borders were drawn for the new state of Alabama, Walker lobbied strenuously to ensure that most of the Tombigbee River was included within its borders, and he was successful in his efforts to have Huntsville chosen as a temporary capital and site of the state constitutional convention.

The federal government appointed Walker as a territorial judge in March 1819, but he resigned in September, after the constitution was adopted. He was elected to the constitutional convention and unanimously chosen president. He greatly influenced the document by appointing the committee which drafted it and choosing its chairman. He successfully proposed the elimination of the federal ratio in determining representation and defeated efforts to limit counties’ representation, concepts promoted by South Alabama, in an effort to weaken the advantage North Alabama would gain if actual numbers of people were counted. He supported the creation of a state bank and lobbied to weaken regulations on interest rates, positions that stood to benefit himself and his wealthy Broad River associates. As a result, they became publicly branded as the “Royal Party,” a distinction that led to their 1821 loss of the governorship to Israel Pickens.

In November 1819, in a compromise bow to North/South sectionalism in the state, the state Senate sent Walker and William Rufus King of South Alabama to the U.S. Senate. At the urging of the Alabama Constitutional Convention, Walker introduced an amendment to include West Florida in the state boundaries of Alabama, but it was narrowly defeated. Most southern senators voted against the measure, an action Walker believed resulted from fear that a larger, new state would have too much power. One month later, on December 14, 1819, Walker’s efforts were rewarded when Alabama was granted statehood.

Working to promote the interests of his supporters in the banking and lending industries, Walker opposed the passage of a bankruptcy bill, defeated in the House of Representatives, that would have afforded more protections to debtors. He and King supplied the winning votes rejecting a proposed tariff, which he felt would harm southern agricultural interests. He was delighted that the federal government set aside three percent of Alabama land sales for internal improvements, although he opposed money for internal improvements elsewhere.

In the summer of 1820 Alabama owed 53 percent of the land debt. Walker strongly supported the Land Law of 1820, which reduced the price of land to $1.25 an acre and ended the credit system. Although implemented, it offered no substantial relief. Walker, therefore, introduced a bill that became the Land Law of 1821. It provided for the relinquishment of lands, resale by the government and return to the original owner of proceeds above $1.25 an acre with discounts for prompt payments. This law made Walker a hero and by September 1821 reduced the Alabama land debt in half.

Despite low cotton prices and bad weather, Walker’s lands continued to provide him with a good income. Perhaps because of his declining health, his wife, Matilda, and his newborn sixth son, William Memorable, accompanied him to Washington in late 1821. Two months after the trip, the Walkers learned that their two-year-old son, Charles Henry, had died in Alabama. After the legislative session, Walker’s health worsened. He resigned his seat on November 21, 1822, and returned to Huntsville, where he died on April 23, 1823. He is buried in Maple Hill Cemetery.

Further Reading

- Abernathy, Thomas P. The Formative Period in Alabama, 1815-1828. Montgomery: Brown Printing, 1922.

- Bailey, Hugh C. John Williams Walker: A Study in the Political, Cultural and Social Life of the Old Southwest. 1964. Reprint, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2003.

- ———. “John W. Walker and the Land Laws of 1820’s.” Agricultural History 37 (April 1950): 120-26.