Little Cahaba Iron Works

Little Cahaba Iron Works (Brighthope)

In 1848, entrepreneur, lawyer, and businessman William Phineas Browne established the Little Cahaba Iron Works, which he named Brighthope, on the banks of the Little Cahaba River in Bibb County. One of Alabama‘s earliest industrial sites, its ruins are ironically situated on what is likely the most biologically diverse piece of land in the state. The precise history of the Little Cahaba Iron Works has become clouded with the passage of time. Early historians of Alabama’s coal and iron industries observed its ruins in the first decade of the twentieth century and described the site as having been home to a blast furnace. Given the time period, as well as the conjecture of Eugene A. Smith in the Geological Survey of Alabama for 1875, modern researchers believe that the site was more likely that of a forge. Nevertheless, the Little Cahaba Iron Works played an important role in the development of Alabama’s iron industry. It began producing iron in the early 1850s, and production continued intermittently until the structure was destroyed in April 1865 during the Civil War.

Little Cahaba Iron Works (Brighthope)

In 1848, entrepreneur, lawyer, and businessman William Phineas Browne established the Little Cahaba Iron Works, which he named Brighthope, on the banks of the Little Cahaba River in Bibb County. One of Alabama‘s earliest industrial sites, its ruins are ironically situated on what is likely the most biologically diverse piece of land in the state. The precise history of the Little Cahaba Iron Works has become clouded with the passage of time. Early historians of Alabama’s coal and iron industries observed its ruins in the first decade of the twentieth century and described the site as having been home to a blast furnace. Given the time period, as well as the conjecture of Eugene A. Smith in the Geological Survey of Alabama for 1875, modern researchers believe that the site was more likely that of a forge. Nevertheless, the Little Cahaba Iron Works played an important role in the development of Alabama’s iron industry. It began producing iron in the early 1850s, and production continued intermittently until the structure was destroyed in April 1865 during the Civil War.

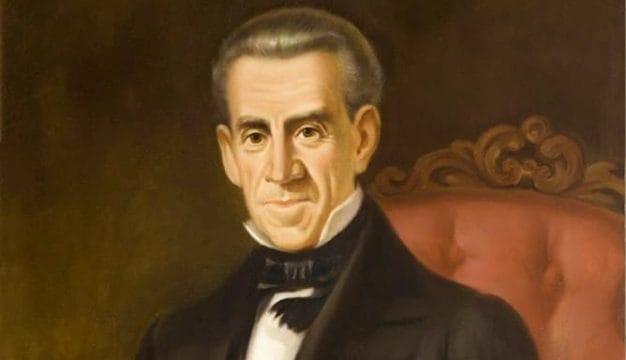

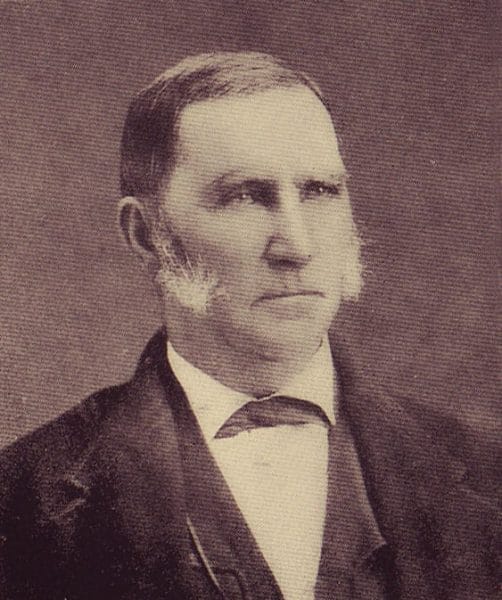

William Phineas Browne

The region in which the ironworks was founded is rich in minerals, including iron ore, limestone, and coal. Early settlers attempted to exploit the iron ore using crude smelting processes, but true forges were not built in the area until the 1830s. Daniel Hillman of New Jersey built one of the first in the area on a site later occupied by the Tannehill Furnace near present-day Bessemer. In about 1836, Jonathan Ware, a transplanted New Englander, built Mahan Forge for John Mahan, an early settler and a veteran of the War of 1812, on Shoal Creek near the future site of Confederate administrator Josiah Gorgas‘s Brierfield Furnace and near present-day Montevallo. These early forges produced chunks of iron that local blacksmiths purchased and fashioned into farm implements and cooking utensils. Three more forges soon emerged in the area, all on property originally owned by Jonathan Newton Smith.

William Phineas Browne

The region in which the ironworks was founded is rich in minerals, including iron ore, limestone, and coal. Early settlers attempted to exploit the iron ore using crude smelting processes, but true forges were not built in the area until the 1830s. Daniel Hillman of New Jersey built one of the first in the area on a site later occupied by the Tannehill Furnace near present-day Bessemer. In about 1836, Jonathan Ware, a transplanted New Englander, built Mahan Forge for John Mahan, an early settler and a veteran of the War of 1812, on Shoal Creek near the future site of Confederate administrator Josiah Gorgas‘s Brierfield Furnace and near present-day Montevallo. These early forges produced chunks of iron that local blacksmiths purchased and fashioned into farm implements and cooking utensils. Three more forges soon emerged in the area, all on property originally owned by Jonathan Newton Smith.

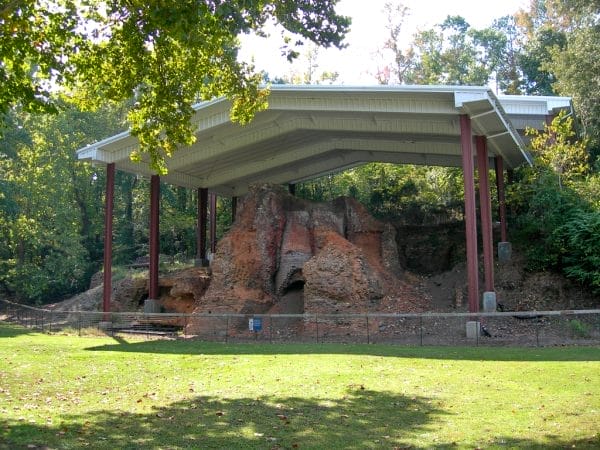

Ruins of Brierfield Iron Works

On September 2, 1846, Browne relocated from New England and obtained the land that would become home to the Little Cahaba Iron Works. He named the site “Brighthope,” perhaps because of state geologist Michael Tuomey‘s observation that “[t]here is enough ore in sight to run a hundred furnaces a hundred years.” The area surrounding Brighthope features a rich coal seam that runs in a steep ridge to within a few feet of the furnace site and then proceeds under the river bed to the ridge on the opposite shore. A nearby mountain of limestone slopes steeply down to the river’s edge.

Ruins of Brierfield Iron Works

On September 2, 1846, Browne relocated from New England and obtained the land that would become home to the Little Cahaba Iron Works. He named the site “Brighthope,” perhaps because of state geologist Michael Tuomey‘s observation that “[t]here is enough ore in sight to run a hundred furnaces a hundred years.” The area surrounding Brighthope features a rich coal seam that runs in a steep ridge to within a few feet of the furnace site and then proceeds under the river bed to the ridge on the opposite shore. A nearby mountain of limestone slopes steeply down to the river’s edge.

In around 1847, in anticipation of establishing a forge, Browne built a dam and a flume to provide power. Historian Ethel Armes describes the dam as “once one of the seven wonders of Bibb County.” The dam was an engineering marvel for its time: Cables stretched across the river and were securely fastened in the solid limestone ridges on each side of the river. Near the site of the dam on the north shore, builders carved steps into the steep side of this limestone precipice, and they are still visible today. Many years after the demise of the furnace, local residents referred to the area as “Browne’s Dam,” rather than Brighthope or Little Cahaba Iron Works. In 1848, Browne constructed a stone furnace stack on the north bank of the Little Cahaba River approximately 150 yards downstream from the dam.

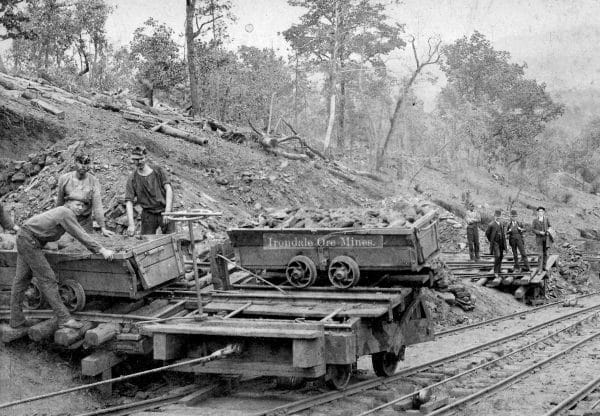

Irondale Ore Mine

These early furnaces were conical in shape and constructed of limestone, though in the case of Brighthope, it was sandstone. The interior chimney was lined with fire-proof bricks. Specific amounts of coal or charcoal, limestone, and iron ore were dumped through the top of the furnace as a water-powered bellows blasted air into the mixture. At about 2,700 degrees, the iron in the ore began to liquefy and collect at the furnace bottom in the crucible. The limestone helped draw out the impurities from the ore and form liquid slag, or waste material, which floated atop the iron. The molten iron was then released from the furnace and funneled into sand molds to make ingots or into castings of iron products. Pig-iron ingots were further processed into wrought iron for tools and weapons.

Irondale Ore Mine

These early furnaces were conical in shape and constructed of limestone, though in the case of Brighthope, it was sandstone. The interior chimney was lined with fire-proof bricks. Specific amounts of coal or charcoal, limestone, and iron ore were dumped through the top of the furnace as a water-powered bellows blasted air into the mixture. At about 2,700 degrees, the iron in the ore began to liquefy and collect at the furnace bottom in the crucible. The limestone helped draw out the impurities from the ore and form liquid slag, or waste material, which floated atop the iron. The molten iron was then released from the furnace and funneled into sand molds to make ingots or into castings of iron products. Pig-iron ingots were further processed into wrought iron for tools and weapons.

John Newton Smith

Browne owned the nearby Montevallo coalmines, and he and several other local entrepreneurs joined him in the operation of the Little Cahaba Iron Works. His principal partners were Jonathan Newton Smith and Alexander K. Shepard. Smith was a local iron master, or furnace manager, and owner of much of the iron-bearing land in the area. Scholars believe that the furnace was idle for a time before the Civil War, but sometime during the war the property was leased to W. L. Ward Company, which signed a contract with the Confederate government presumably to supply iron to the Confederate ironworks at Selma. A second and larger stack had been built by this time within a few yards of the older furnace. This stack was 29 feet in height, nine feet higher than the original furnace, and was listed by the Confederate Nitre and Mining Bureau as being in operation in 1864. In April 1865, Union general James H. Wilson led a force, known as Wilson’s Raiders, through the area, and they destroyed the Brighthope furnaces and several others.

John Newton Smith

Browne owned the nearby Montevallo coalmines, and he and several other local entrepreneurs joined him in the operation of the Little Cahaba Iron Works. His principal partners were Jonathan Newton Smith and Alexander K. Shepard. Smith was a local iron master, or furnace manager, and owner of much of the iron-bearing land in the area. Scholars believe that the furnace was idle for a time before the Civil War, but sometime during the war the property was leased to W. L. Ward Company, which signed a contract with the Confederate government presumably to supply iron to the Confederate ironworks at Selma. A second and larger stack had been built by this time within a few yards of the older furnace. This stack was 29 feet in height, nine feet higher than the original furnace, and was listed by the Confederate Nitre and Mining Bureau as being in operation in 1864. In April 1865, Union general James H. Wilson led a force, known as Wilson’s Raiders, through the area, and they destroyed the Brighthope furnaces and several others.

Dwarf Horse Nettle

Several local business men unsuccessfully attempted to revive the ironworks on the Little Cahaba after the Civil War. The Brighthope ruins have mostly disappeared, but some stone foundation remnants and slag from the furnace or forge can still be seen on the banks of the river. The property is now within the Cahaba National Wildlife Refuge and is owned by the Nature Conservancy of Alabama. Now known as the Kathy Stiles Freeland Bibb County Glades Preserve, the property is home to 61 rare plant species, eight of which had never previously been known to science. The Little Cahaba River, which runs through the preserve, is a safe haven for dozens of rare aquatic species, including the round rocksnail and the goldline darter. This unique mid-nineteenth century industrial site is indeed a “Brighthope” for future generations.

Dwarf Horse Nettle

Several local business men unsuccessfully attempted to revive the ironworks on the Little Cahaba after the Civil War. The Brighthope ruins have mostly disappeared, but some stone foundation remnants and slag from the furnace or forge can still be seen on the banks of the river. The property is now within the Cahaba National Wildlife Refuge and is owned by the Nature Conservancy of Alabama. Now known as the Kathy Stiles Freeland Bibb County Glades Preserve, the property is home to 61 rare plant species, eight of which had never previously been known to science. The Little Cahaba River, which runs through the preserve, is a safe haven for dozens of rare aquatic species, including the round rocksnail and the goldline darter. This unique mid-nineteenth century industrial site is indeed a “Brighthope” for future generations.

Further Reading

- Armes, Ethel. The Story of Coal and Iron in Alabama. 1910. Reprint, Leeds, Ala.: Beechwood Books, 1987.

- Bennett, James R. Tannehill and the Growth of the Alabama Iron Industry, Including the Civil War in West Alabama. McCalla, Ala.: Alabama Historic Ironworks Commission, 1999.

- Joseph H. Woodward, II. Alabama Blast Furnaces. Woodward, Ala.: Woodward Iron Company, 1940.

- “Old ‘Brighthope,’ First Blast Furnace in Bibb County, Now Lies Serene and Still.” Birmingham News-Age Herald, June 23, 1929.