Southeastern Indians and the American Revolution

Southeastern Indians participated in the American Revolution for a variety of reasons and with varying results. Throughout the colonial period in North America, wars between European powers forced Indian peoples to choose sides or find ways to stay neutral, and the American Revolution was no exception. Most of the southeastern Indians who fought in the war supported Britain against the United States or Spain, but some gave aid to the Americans and the Spanish. For example, the Catawbas fought on the American side, but the Creeks, Chickasaws, and Choctaws generally supported Britain. Many factions and individuals among the South’s Indian groups also pursued their own policies and actions, however, based on what they perceived to be their best interests. Thus no southeastern Indian group can be accurately termed “pro-British,” “pro-American,” or “pro-Spanish” because none blindly followed orders from any single foreign power.

Cherokees

In the Southeast, the American Revolution proved most disastrous for the Cherokees. With a population of about 8,500, the Cherokees began sending out war parties against outlying white settlements in the Carolinas and Georgia in the spring of 1776 in retaliation for illegal encroachments on their lands. Their primary leader was a young warrior named Dragging Canoe (Tsi’yugûnsi’ny), the son of the venerable Cherokee chief Attakullakulla. Dragging Canoe had warned other Cherokees and the British at the signing of the Sycamore Shoals Treaty in March 1775 in eastern Tennessee that the Cherokees should resist any further encroachments on their land or risk being overrun. The willingness of Dragging Canoe and other warriors to take the fight to white settlers stemmed in part from a generational split among the Cherokees: young warriors increasingly distrusted their elders’ abilities to prevent further land loss. After initial successes in their attacks, the Cherokees soon witnessed four American armies from Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia invade nearly all their villages during the summer and fall of 1776. Cherokee chiefs sued for peace in spring 1777 and agreed to still more land cessions, while Dragging Canoe and hundreds of other Cherokees moved south and west to establish new villages on Chickamauga Creek. There they became known as the Chickamauga Cherokees and continued to resist the Americans.

Catawbas

The Catawbas, whose villages and few hundred people were located in the Piedmont area along the border of South Carolina and North Carolina and were surrounded by pro-American settlers, took up arms against the British as early as 1775. Their warriors participated in numerous key battles throughout the South, recaptured enslaved people who had escaped, and assisted the Americans in fighting the Cherokees. When the British invaded the South in 1780, the Catawba villages temporarily became a refuge for American troops. But the Catawbas were soon forced by British troops to flee their homes and move north into Virginia. The British burned the Catawba villages and confiscated all of their cattle and other possessions. In 1782, however, after Gen. Charles Cornwallis’s surrender to the Americans and the French at Yorktown, the Catawbas returned home, and a grateful South Carolina paid the Indians for their services. The Catawbas also secured a state-recognized reservation in their traditional homeland as a result of their support for the American side, which they still occupy today.

Creeks

As one of the South’s largest Indian groups, with a population of around 15,000, the Creeks could have dramatically affected the direction of the war in the South. Factionalism played a role in preventing a unified Creek stance, however, because Creek towns were divided among the Upper Towns and Lower Towns, with each group pursuing its own foreign policies. Access to European manufactured goods through the deerskin trade concerned the Creeks more than any other single issue, with American and British traders seeking Creek deerskins and loyalties. The Revolutionary War both threatened the viability of the trade and provided opportunities for Creek men to acquire trade goods by providing military services, especially on behalf of Britain against Spain during the Mobile and Pensacola campaigns of 1780–81. Still other Creeks, most notably the mixed-race leader Alexander McGillivray, used the Anglo-American conflict to strengthen their political positions by taking leadership roles in diplomacy. McGillivray continued to gather political power and influence among the Creeks in dealings with the United States after the war. Yet, the Creeks never employed their large population in significant sustained fighting during the war, preferring to protect their sovereignty and trade through cautious participation.

Choctaws

As with the Creeks, Choctaw concerns during the American Revolution centered around keeping access to European trade goods. Additionally, the Choctaws were one the South’s largest Indian groups with a population of around 15,000 that was divided among 50 villages in three distinct and independent political divisions. At the start of the Revolutionary War, the British hired Choctaw warriors to patrol the Mississippi River against American attacks. Despite these efforts, in February 1778 American Army captain James Willing led an expedition down the Mississippi River that attacked British settlements all the way to New Orleans. The British responded the only way they could—by organizing a force of Choctaw Indians to march to the British-held town of Natchez, Mississippi, and protect the town. The Choctaw force of 155 men never fought against the Americans, who had retreated to Spanish New Orleans, but they did convince Natchez residents to remain pro-British. When Spain declared war on Britain in 1779, hundreds of Choctaw warriors helped the British defend Mobile in 1780 and Pensacola in 1780–81, even as a much smaller number of Choctaws supported Spain. Ultimately, British forces in those towns surrendered to Spain, and the Choctaws were left after the war seeking trade with Spain, the United States, and individual American states.

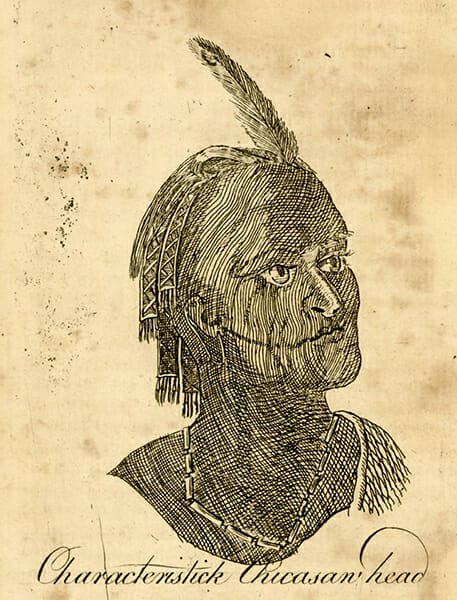

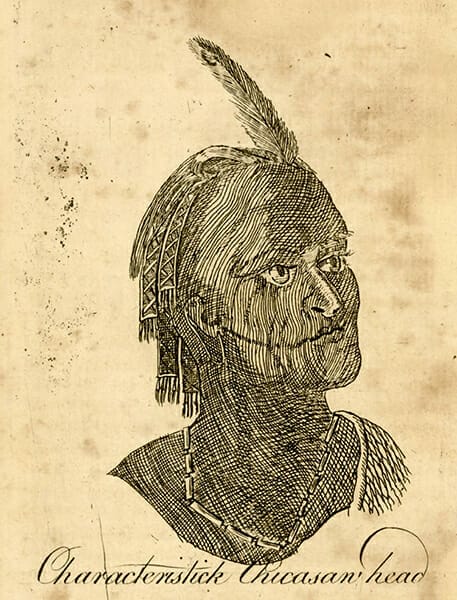

Chickasaws

The Chickasaws were Britain’s staunchest southeastern allies throughout the eighteenth century. Though at about 4,000 their numbers were significantly fewer than the Choctaws and Creeks, the Chickasaws also patrolled the Mississippi River to prevent American attacks, and some of their warriors engaged in fighting against American colonel George Rogers Clark’s forces in present-day Illinois. The Chickasaws also sent small groups of warriors to assist Britain in defending Mobile and Pensacola against Spain. Most famously, Chickasaw chiefs responded to a threat from the state of Virginia to stay out of the war by challenging Virginia forces to meet them halfway between Virginia and their north Mississippi homeland and suffer defeat, as had all Chickasaw enemies in the eighteenth century. After the war, the Chickasaws also sought trade relations with Spain and the new United States.

Further Reading

- Bunn, Mike. Fourteenth Colony: The Forgotten Story of the Gulf South During America’s Revolutionary Era. Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2020.

- Calloway, Colin G. The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- O’Brien, Greg. Choctaws in a Revolutionary Age, 1750–1830. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

- O’Donnell, James H., III. Southern Indians in the American Revolution. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1973.

- Wood, Peter H. “George Washington, Dragging Canoe, and Southeastern Indian Resistance.” In George Washington’s South, edited by Tamara Harvey and Greg O’Brien. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004.