Plan of Civilization

Benjamin Hawkins and the Creek Indians

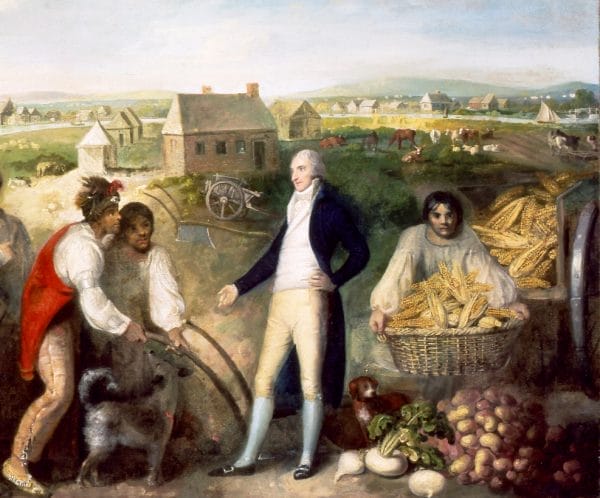

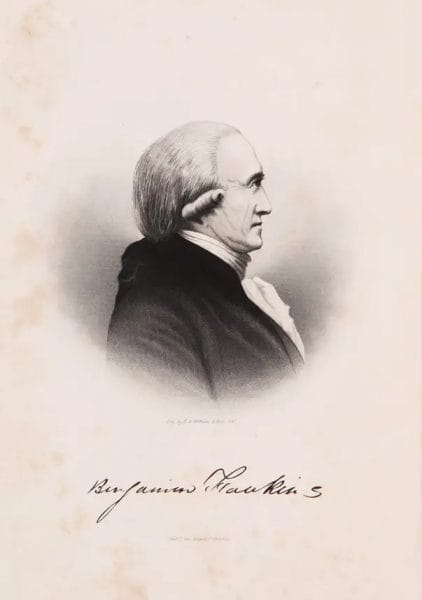

The plan of civilization was a federal development program created in the 1790s to address the so-called “Indian problem,” the much-debated question among American politicians about how to go about opening up American Indian lands to Euro-American settlement. The task of implementing the plan of civilization among the Creek Indians of present-day Alabama and Georgia went to federal Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins, who lived among the Creeks from 1796 until his death in 1816. The stated purpose of the plan of civilization was to train Indian men and women in ranching, farming, and cottage industries such as cloth making. The public face of the plan suggested that through such training Indians would become self-sufficient farmers, selling small surpluses on the market. The underlying goal of the plan, however, was to settle Indians on small farms and thus force them to give up hunting on their vast territories. Then, as American needs for land increased, the Indians in theory would be more willing to give up their holdings. The federal and state governments, so the thinking went, then could acquire peacefully Indian lands through treaty.

Benjamin Hawkins and the Creek Indians

The plan of civilization was a federal development program created in the 1790s to address the so-called “Indian problem,” the much-debated question among American politicians about how to go about opening up American Indian lands to Euro-American settlement. The task of implementing the plan of civilization among the Creek Indians of present-day Alabama and Georgia went to federal Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins, who lived among the Creeks from 1796 until his death in 1816. The stated purpose of the plan of civilization was to train Indian men and women in ranching, farming, and cottage industries such as cloth making. The public face of the plan suggested that through such training Indians would become self-sufficient farmers, selling small surpluses on the market. The underlying goal of the plan, however, was to settle Indians on small farms and thus force them to give up hunting on their vast territories. Then, as American needs for land increased, the Indians in theory would be more willing to give up their holdings. The federal and state governments, so the thinking went, then could acquire peacefully Indian lands through treaty.

The plan of civilization conspicuously ignored the fact that the American Indians, many of whom had been agriculturalists for millennia, were already more than capable of clothing and feeding themselves. Moreover, the Creeks and other southern Indian groups were already experimenting with cash crops, and they had already diversified their market endeavors with cattle and hog ranching when the deerskin trade began to decline after the American Revolution.

Hawkins used money, in the form of annuities that the Creeks acquired through land cessions to purchase spinning wheels, looms, plows, cotton gins, blacksmith tools, and other articles he thought necessary to implement the plan of civilization. Because of the plan’s agricultural base, Hawkins consulted much with Creek women, who, in Creek society, were in charge of the farming. Hawkins knew that their support would be instrumental to the success of the plan and was pleasantly surprised when they embraced it. Creek women generally were protective of traditional Creek culture, but in the agricultural sphere, they were quite progressive. They had been experimenting with introduced crops throughout the colonial era, and by the end of the eighteenth century, sweet potatoes, and rice were grown along with the indigenous corn, beans, and squash they had grown for centuries. They had also begun experimenting with commercial crops such as cotton, and with Hawkins’s aid, they intensified those efforts. Creek women also learned spinning and weaving. Even though they could still make cloth by finger-weaving indigenous fibers, they preferred European-manufactured cloth, which they had been buying since it first became available over a century earlier. Under the plan of civilization they now had the necessary machinery to make cloth more efficiently, thus freeing them from having to purchase it.

Benjamin Hawkins

One crucial aspect of the plan that inspired much resistance among the Creeks was the curbing of men’s hunting activities. Among the Creeks, women farmed and men hunted, and to be a man was to be a hunter. A man working in the fields was a source of ridicule, and men were offended and embarrassed at being asked to undertake agricultural work. Hunting also was tied closely to Creek national territories. In their treaty negotiations, Creek representatives invariably argued against land cessions on the grounds that they needed all of their land for hunting, and hunting was considered a legitimate and mutually recognized claim to national lands. In Creek eyes, then, giving up the hunt was tantamount to giving up their land. So, even though Creek men recognized that the deerskin trade was floundering and that they needed a commercial alternative to it, they refused to abandon commercial hunting.

Benjamin Hawkins

One crucial aspect of the plan that inspired much resistance among the Creeks was the curbing of men’s hunting activities. Among the Creeks, women farmed and men hunted, and to be a man was to be a hunter. A man working in the fields was a source of ridicule, and men were offended and embarrassed at being asked to undertake agricultural work. Hunting also was tied closely to Creek national territories. In their treaty negotiations, Creek representatives invariably argued against land cessions on the grounds that they needed all of their land for hunting, and hunting was considered a legitimate and mutually recognized claim to national lands. In Creek eyes, then, giving up the hunt was tantamount to giving up their land. So, even though Creek men recognized that the deerskin trade was floundering and that they needed a commercial alternative to it, they refused to abandon commercial hunting.

Because of the economic uncertainties of the deerskin trade, many Creek men and women had already turned to commercial livestock raising. In fact, Hawkins found the Creeks well on the road to becoming ranchers at the time of his arrival in 1796. Almost every family owned cattle, hogs, and horses, and some individuals owned large herds. The Creeks raised cattle and hogs, in part, for their own consumption, but Creek ranchers drove most of their stock to markets in Mobile and Pensacola, where they were sold on the hoof. They used the proceeds to purchase cloth, guns, ammunition, metal goods, and other manufactured items. Some Creek families became full-time ranchers and began to acquire substantial wealth, and a few used their assets to purchase African slaves. These Creeks adopted American notions of private property, and, by the late eighteenth century, clear class divisions had emerged in Creek society.

The plan of civilization, on its surface, fit well within the changing economic situation of Creek life at the end of the 18th century. But Creek opinion about the program had been divided from the beginning. Every Creek man and woman understood that America’s underlying motivation of the civilization plan was land acquisition, and this fostered tensions between those who viewed the plan as necessary to their cultural survival and those who viewed it as heralding its destruction. These tensions contributed to a Creek civil war, known as the Creek War of 1813-14. The Red Sticks, Creek rebels likely named after the red war clubs they carried, directed their wrath against anything and anyone associated with the plan of civilization. They threw Creek-owned plows and looms into the rivers. They killed hogs, horses, and cattle, all symbols of America and the plan of civilization. Fearing an uprising, the United States government sent troops under Andrew Jackson to engage the Red Sticks, who were finally defeated in August 1814 at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. Afterwards, the devastated Creeks tried to rebuild their national economy through farming and stock raising. By this time, however, American officials saw expulsion rather than the plan of civilization as a more expedient way to deal with the “Indian problem,” and they dropped the effort in favor of forcing the Indians to relocate to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), accomplished through the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

Additional Resources

Braund, Kathryn E. Holland. Deerskins and Duffels: The Creek Indian Trade with Anglo-America, 1685–1815. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993.

Ethridge, Robbie. Creek Country: The Creek Indians and Their World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Hawkins, Benjamin. The Collected Works of Benjamin Hawkins, 1796–1810, edited by H. Thomas Foster, II. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

Martin, Joel W. Sacred Revolt: The Muskogee’s Struggle for a New World. Boston: Beacon Press, 1991.

Saunt, Claudio. A New Order of Things: Property, Power, and the Transformation of the Creek Indians, 1733–1816. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.