CSS Nashville

CSS Nashville

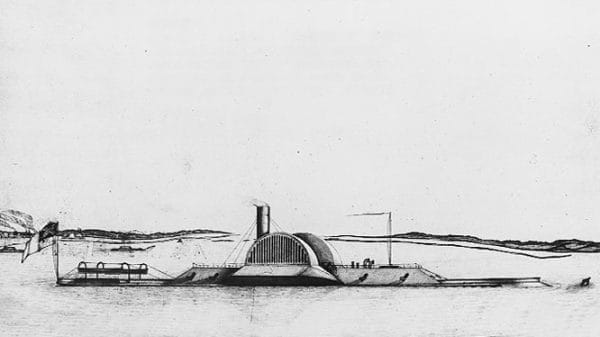

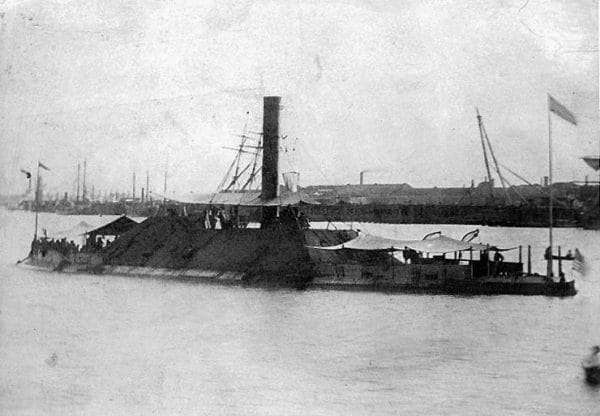

The CSS Nashville, built in Montgomery, Montgomery County, was one of the last ironclads constructed by the Confederacy during the Civil War and one of the last major Confederate ships to see action before the end of the war, and probably the only ironclad constructed in Montgomery. The Nashville was outfitted with the most advanced naval armaments of the era.

CSS Nashville

The CSS Nashville, built in Montgomery, Montgomery County, was one of the last ironclads constructed by the Confederacy during the Civil War and one of the last major Confederate ships to see action before the end of the war, and probably the only ironclad constructed in Montgomery. The Nashville was outfitted with the most advanced naval armaments of the era.

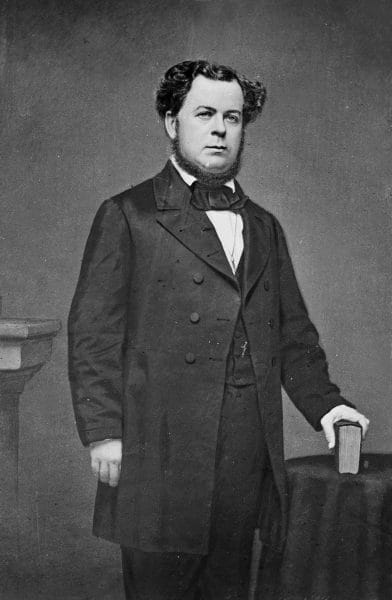

The construction of the CSS Nashville and other southern ironclads was prompted by Confederate secretary of the navy and former U.S. senator from Florida Stephen R. Mallory, who was greatly concerned about the South’s lack of naval power. When the 11 southern states seceded from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America, they had the makings of an army but none of a navy. The new government had to improvise one largely from scratch and with little seafaring tradition and few warships or naval facilities, as compared with the United States.

Stephen R. Mallory

Mallory improvised a four-point maritime strategy: the Confederate Navy would forego existing naval shipbuilding doctrine in favor of new technology, including armored warships, submarines, and mines (then called “torpedoes”); it would build a fleet of ironclads to defend southern harbors and rivers and prevent invasions by the U.S. Navy into the southern interior; it would construct a fleet of swift blockade runners to bring critically needed arms and supplies into the Confederacy; and it would hire or commission raiders to destroy federal merchant vessels. The Confederacy contracted various shipbuilders for 50 armored warships and by extraordinary efforts 22 were commissioned and sent into battle. The most famous were the first CSS Virginia, the CSS Arkansas, the CSS Tennessee, and the CSS Nashville. The Confederate navy also possessed a different ship named the CSS Nashville, a blockade runner that was sunk.

Stephen R. Mallory

Mallory improvised a four-point maritime strategy: the Confederate Navy would forego existing naval shipbuilding doctrine in favor of new technology, including armored warships, submarines, and mines (then called “torpedoes”); it would build a fleet of ironclads to defend southern harbors and rivers and prevent invasions by the U.S. Navy into the southern interior; it would construct a fleet of swift blockade runners to bring critically needed arms and supplies into the Confederacy; and it would hire or commission raiders to destroy federal merchant vessels. The Confederacy contracted various shipbuilders for 50 armored warships and by extraordinary efforts 22 were commissioned and sent into battle. The most famous were the first CSS Virginia, the CSS Arkansas, the CSS Tennessee, and the CSS Nashville. The Confederate navy also possessed a different ship named the CSS Nashville, a blockade runner that was sunk.

USS Tennessee

On September 16, 1862, Mallory contracted with two builders to construct the ironclad Nashville in Montgomery for nearly $670,000, a huge sum at the time. The improvised shipyard was located at Cypress Creek inlet, just above the city wharf. The Confederate States Naval Iron Works at Columbus, Georgia, supervised the construction and supplied two steam engines for Nashville’s side paddle wheels. Crews finished with the initial stages of construction on May 20, 1863, and launched the ship sideways with a huge splash into the Alabama River. Nashville was a large vessel for the river, 271 feet long and 62½ feet across, about the same length and beam as the famous Delta Queen, a paddle wheel steamboat still in operation. The Nashville displaced considerably more water, however, as a result of the additional weight from armaments and armor.

USS Tennessee

On September 16, 1862, Mallory contracted with two builders to construct the ironclad Nashville in Montgomery for nearly $670,000, a huge sum at the time. The improvised shipyard was located at Cypress Creek inlet, just above the city wharf. The Confederate States Naval Iron Works at Columbus, Georgia, supervised the construction and supplied two steam engines for Nashville’s side paddle wheels. Crews finished with the initial stages of construction on May 20, 1863, and launched the ship sideways with a huge splash into the Alabama River. Nashville was a large vessel for the river, 271 feet long and 62½ feet across, about the same length and beam as the famous Delta Queen, a paddle wheel steamboat still in operation. The Nashville displaced considerably more water, however, as a result of the additional weight from armaments and armor.

After launch, Nashville travelled downriver to the Navy yard at Selma, where the CSS Tennessee had been built, for further outfitting. The ship then was towed to Mobile. To cross the Dog River Bar with its mere 10 feet of water, the Nashville had to be equipped with flotation devices called “camels.” The Nashville arrived in Mobile Bay on June 16, 1863, where it was scheduled to be clad stem to stern in iron plating. However, the plating was scarce, and thus the vessel never was completely outfitted with armor plate before the war’s end. The ship was also to be fitted with an array of one 24-pounder howitzer and seven Brooke rifled guns cast in Selma, the most advanced naval ordnance of the Civil War. Because of the slope of the ship’s armor, however, the Nashville required longer guns, and the iron works in Selma was able to complete only three.

David G. Farragut

Confederate naval officers were concerned about her weaknesses, including exposed side wheels, slow speed, and inadequate armor as of the spring of 1864. Adm. David G. Farragut, commander of the U.S. naval forces in the Gulf, worried about the threat the ship could pose to his impending attack upon Mobile Bay were it to link up there with the CSS Tennessee. He need not have worried: The Nashville, unready to defend the entrance to the bay, did not participate in the August 5 battle, but lay moored to a wharf in upper Mobile Bay.

David G. Farragut

Confederate naval officers were concerned about her weaknesses, including exposed side wheels, slow speed, and inadequate armor as of the spring of 1864. Adm. David G. Farragut, commander of the U.S. naval forces in the Gulf, worried about the threat the ship could pose to his impending attack upon Mobile Bay were it to link up there with the CSS Tennessee. He need not have worried: The Nashville, unready to defend the entrance to the bay, did not participate in the August 5 battle, but lay moored to a wharf in upper Mobile Bay.

The Nashville saw brief action at the very end of the war, however, and was the last major Confederate warship to engage federal forces. In early 1865, U.S. Army troops advanced up the eastern shore of Mobile Bay to take the city of Mobile from the rear. They aimed to drive north into central Alabama to link up with forces heading south toward Selma and Montgomery. The CSS Nashville, and three smaller gunboats defending upper Mobile Bay in late March and early April, furnished vigorous covering fire for the evacuation of two Confederate strongholds, Spanish Fort and Fort Blakeley. In one of the tributaries of the bay, the Nashville kept federal ships at bay and suffered some artillery fire that did little damage. The forts, however, fell to U.S. forces on April 8–9, 1865. On the afternoon of April 9th, Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered to Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. On May 4, Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, son of President Zachary Taylor, surrendered the remaining Confederate forces east of the Mississippi River at Citronelle, Alabama. The Nashville’s captain surrendered the ship a few days later, and the U.S. Navy subsequently purchased the ship. The ship was then sold at auction in November 1867 and was scrapped.

Further Reading

- Luraghi, Raimondo. A History of the Confederate Navy. Translated by Paolo E. Coletta. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1996.

- Napier, John H., III. “Montgomery’s Confederate Warship.” MCHS Herald 13 (Fall 2005): 6–9.

- Still, William N., Jr. Iron Afloat: The Story of the Confederate Armorclads. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1985.

- ———. Confederate Shipbuilding. Athens: University of Georgia Press 1969.