Josiah Gorgas

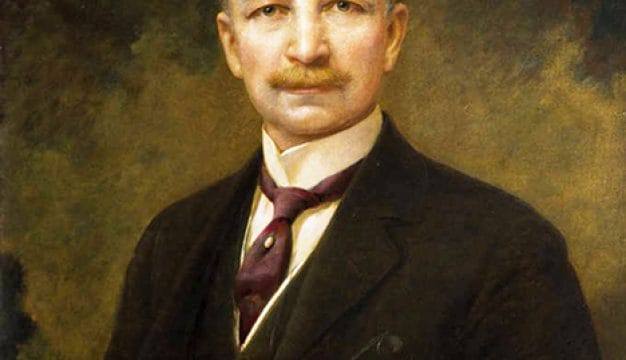

Josiah Gorgas, ca. 1878

Josiah Gorgas (1818-1883), a career army officer and chief of the Confederate Bureau of Ordnance, was born on July 1, 1818, in Running Pumps, Pennsylvania, the son of Sophia Atkinson and Joseph Gorgas, a clockmaker, farmer, innkeeper, and mechanic. Josiah received little formal education until the age of 17, when he went to live with an older sister and her family in Lyons, New York. There a local congressman noticed Josiah and secured him an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York.

Josiah Gorgas, ca. 1878

Josiah Gorgas (1818-1883), a career army officer and chief of the Confederate Bureau of Ordnance, was born on July 1, 1818, in Running Pumps, Pennsylvania, the son of Sophia Atkinson and Joseph Gorgas, a clockmaker, farmer, innkeeper, and mechanic. Josiah received little formal education until the age of 17, when he went to live with an older sister and her family in Lyons, New York. There a local congressman noticed Josiah and secured him an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York.

Gorgas graduated sixth in his class in 1841 and chose to serve in the U.S. Ordnance Corps. His first posting was at an arsenal in Watervliet, New York, after which he transferred to an arsenal near Detroit, Michigan, and then returned to the Watervliet arsenal. In 1845, he took a leave from the army and travelled to Europe to survey fortifications and armaments. In applying for the leave he became involved in a petty and lasting quarrel with Secretary of War William L. Marcy and Secretary of State James Buchanan. When he returned to duty at Watervliet in May 1846, the Mexican War had begun.

Gorgas was ordered to New York to prepare ordnance for the siege train to be shipped to Mexico. He sailed on the ordnance vessel to Mexico in mid-January 1847 and joined the ordnance staff of Gen. Winfield Scott in Veracruz. While stationed there, he seriously quarreled with Benjamin Huger, chief of ordnance to Scott; the quarrel haunted the remainder of Gorgas’s U.S. and Confederate army careers. While in Veracruz he contracted a mild case of yellow fever. He reached Mexico City only after the fighting had ended, and in July 1848 he returned with Scott’s army to the United States. His quarrels with superiors cost him the brevet promotion that others received for service in the war.

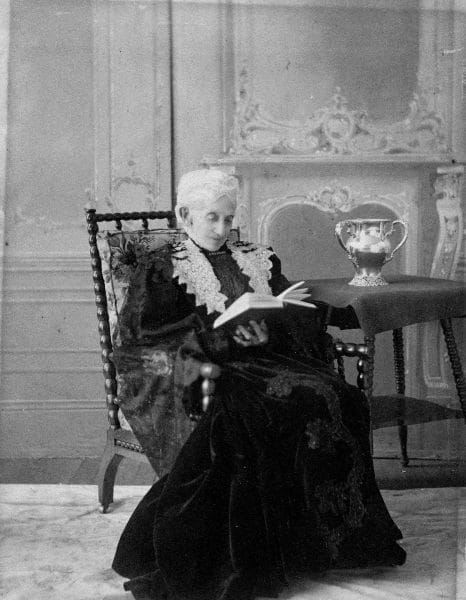

Amelia Gayle Gorgas

Gorgas returned to duty at the arsenal in Watervliet and subsequently served at arsenals in Vermont, New York City, Pittsburgh, and Virginia. Throughout his years in the U.S. Army, Gorgas repeatedly complained to his superiors about people and conditions in his assignments, constantly maneuvering for something better. In June 1853, he began an assignment at the Mount Vernon Arsenal north of Mobile and was soon registering his usual complaints about conditions and requests for a transfer. Then he met Amelia Gayle, daughter of former Alabama governor John Gayle. The complaints to his superiors stopped, and the couple married. They had six children: William Crawford, Jessie, Mary Gayle, Christine Amelia, Maria Bayne, and Richard Haynsworth. Subsequent assignments took them to arsenals in Maine, South Carolina, and Pennsylvania. During these years, his relationships with his army superiors steadily worsened.

Amelia Gayle Gorgas

Gorgas returned to duty at the arsenal in Watervliet and subsequently served at arsenals in Vermont, New York City, Pittsburgh, and Virginia. Throughout his years in the U.S. Army, Gorgas repeatedly complained to his superiors about people and conditions in his assignments, constantly maneuvering for something better. In June 1853, he began an assignment at the Mount Vernon Arsenal north of Mobile and was soon registering his usual complaints about conditions and requests for a transfer. Then he met Amelia Gayle, daughter of former Alabama governor John Gayle. The complaints to his superiors stopped, and the couple married. They had six children: William Crawford, Jessie, Mary Gayle, Christine Amelia, Maria Bayne, and Richard Haynsworth. Subsequent assignments took them to arsenals in Maine, South Carolina, and Pennsylvania. During these years, his relationships with his army superiors steadily worsened.

The Gorgas family was living in Philadelphia when the first southern states seceded in the winter of 1860-61. Josiah declined a commission in the Confederate Army in February, but when he learned of a pending transfer from his duties at Philadelphia’s Frankford Arsenal to foundry duty under Benjamin Huger, he resigned from the U.S. Army effective April 3, 1861. He joined the Confederacy as a major in an artillery unit, and he became chief of the Confederate Bureau of Ordnance on April 8, 1861. Gorgas’s prior army career had not been especially distinguished. His appointment as ordnance chief has been called one of necessity, as he was the only professional ordnance man available to the Confederacy after another officer had refused the position.

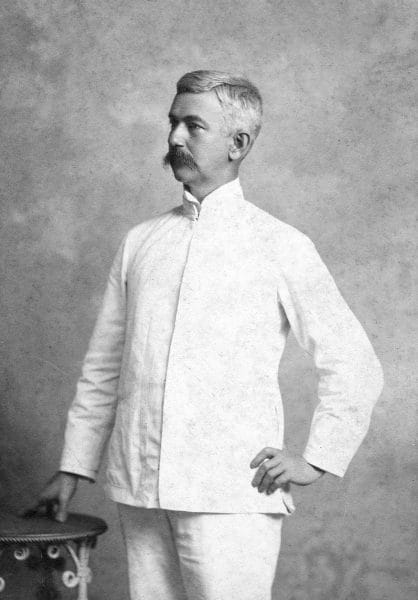

Josiah Gorgas

In 1861, the South possessed little heavy industry capable of providing arms and ammunition to the Confederacy. Gorgas embarked on a three-part plan to provide the army with the hardware of war: scavenge arms from battlefields, import arms and essential manufacturing supplies from Europe, and build an industrial complex to manufacture what the army required. His success was phenomenal, building a system that by 1864 produced vast quantities of war materiel for large armies, despite the enormous handicaps of an inferior southern rail system and self-interested southern governors who hoarded supplies in their own states. He pushed for the creation of the Bureau of Foreign Supplies to arrange for the purchase of supplies from Europe and to procure blockade runners to carry the shipments. Much of his success can be credited to his shrewd judgments as an administrator in the choice of skilled subordinates. Wartime responsibilities drastically matured Gorgas, and the petulant correspondence that had characterized his difficult relationships with prewar superiors and had damaged his career disappeared. Over the course of the war, he rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel, then to colonel, and finally on November 10, 1864, to brigadier general. When Josiah fled Richmond with the Confederate government in April 1865, his family moved in with Amelia’s sister in Richmond. A few months later, the two sisters moved with their children to Maryland.

Josiah Gorgas

In 1861, the South possessed little heavy industry capable of providing arms and ammunition to the Confederacy. Gorgas embarked on a three-part plan to provide the army with the hardware of war: scavenge arms from battlefields, import arms and essential manufacturing supplies from Europe, and build an industrial complex to manufacture what the army required. His success was phenomenal, building a system that by 1864 produced vast quantities of war materiel for large armies, despite the enormous handicaps of an inferior southern rail system and self-interested southern governors who hoarded supplies in their own states. He pushed for the creation of the Bureau of Foreign Supplies to arrange for the purchase of supplies from Europe and to procure blockade runners to carry the shipments. Much of his success can be credited to his shrewd judgments as an administrator in the choice of skilled subordinates. Wartime responsibilities drastically matured Gorgas, and the petulant correspondence that had characterized his difficult relationships with prewar superiors and had damaged his career disappeared. Over the course of the war, he rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel, then to colonel, and finally on November 10, 1864, to brigadier general. When Josiah fled Richmond with the Confederate government in April 1865, his family moved in with Amelia’s sister in Richmond. A few months later, the two sisters moved with their children to Maryland.

Gorgas House

His extraordinary success in the ordnance bureau lulled Gorgas into the assumption that he could succeed equally well in the development of heavy industry in the postwar South. In 1866, he repaired and re-opened the Brierfield Iron Works, a war-damaged industrial site near Montevallo, Shelby County, but the venture failed financially three years later.

Gorgas House

His extraordinary success in the ordnance bureau lulled Gorgas into the assumption that he could succeed equally well in the development of heavy industry in the postwar South. In 1866, he repaired and re-opened the Brierfield Iron Works, a war-damaged industrial site near Montevallo, Shelby County, but the venture failed financially three years later.

In 1869, he became the headmaster at the University of the South at Sewanee, Tennessee. The trustees expected him to raise money, recruit students, teach classes, supervise construction of buildings, and run the school. While he struggled to keep the school financially afloat, his health failed, and trustees blamed him for the school’s difficulties. When the trustees moved to fire him in July 1878, he was elected president of the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, and he left Sewanee. On February 23, 1879, he suffered a massive stroke from which he never fully recovered. When he resigned the university presidency in July 1879, the trustees created the post of university librarian for him and allowed him to remain in the president’s residence. His health steadily declined, and he died in Tuscaloosa on May 15, 1883, and was buried in Evergreen Cemetery.

Gorgas, William Crawford

Although the Confederate Army was frequently short of food and clothing, Gorgas’s remarkable management of the ordnance bureau meant that the army did not lack munitions. He was widely regarded as the most able administrator in the Confederate government. Gorgas’s eldest son, William Crawford, achieved even greater fame than his father. As chief sanitary officer for the United States in Panama, he improved health conditions there, and his work made possible the successful construction of the Panama Canal. William Crawford Gorgas also worked to improve sanitation and health conditions in Africa, Europe, and Central and South America.

Gorgas, William Crawford

Although the Confederate Army was frequently short of food and clothing, Gorgas’s remarkable management of the ordnance bureau meant that the army did not lack munitions. He was widely regarded as the most able administrator in the Confederate government. Gorgas’s eldest son, William Crawford, achieved even greater fame than his father. As chief sanitary officer for the United States in Panama, he improved health conditions there, and his work made possible the successful construction of the Panama Canal. William Crawford Gorgas also worked to improve sanitation and health conditions in Africa, Europe, and Central and South America.

Additional Resources

Vandiver, Frank E. Ploughshares into Swords: Josiah Gorgas and Confederate Ordnance. Austin, Tex.: University of Texas Press, 1952.

Wiggins, Sarah Woolfolk. Love and Duty: Amelia and Josiah Gorgas and Their Family. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 2005.

Wiggins, Sarah Woolfolk, ed. The Journals of Josiah Gorgas, 1857–1878. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 1995.