J. Marion Sims

J. Marion Sims

J. Marion Sims (1813-1883) practiced medicine in central Alabama from 1835 to 1849. He is often credited with being the “father of gynecology,” but his methods and practices continue to cause great controversy regarding his place in medical history. During his Alabama years, he developed medical and surgical techniques and tools that revolutionized the new field of gynecology and through them had a successful career in New York and Europe. But scholars also point out that Sims’s experimental surgeries, which were performed on enslaved women subjected to forced treatment, caused great suffering and helped to prop up the institution of slavery. Sims thus remains a controversial figure in medical history, despite his contributions to the field.

J. Marion Sims

J. Marion Sims (1813-1883) practiced medicine in central Alabama from 1835 to 1849. He is often credited with being the “father of gynecology,” but his methods and practices continue to cause great controversy regarding his place in medical history. During his Alabama years, he developed medical and surgical techniques and tools that revolutionized the new field of gynecology and through them had a successful career in New York and Europe. But scholars also point out that Sims’s experimental surgeries, which were performed on enslaved women subjected to forced treatment, caused great suffering and helped to prop up the institution of slavery. Sims thus remains a controversial figure in medical history, despite his contributions to the field.

James Marion Sims was born on January 25, 1813, in Hanging Rock, Lancaster County, South Carolina, to Jack Sims and Mahala Mackey Sims. He was the oldest of seven children. His family first had a small farm and then an inn in Lancaster, S.C. He attended South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina) and in 1835 earned a medical degree from Philadelphia’s Jefferson Medical College. Upon graduation, Sims opened a practice in Lancaster. His new practice failed within the year after two infants under his treatment died, and he set out for the frontier region of western Alabama. He settled in Macon County, where he earned a living treating slaves on local plantations. In his autobiography, The Story of My Life, Sims described his rural practice as carrying a gun and riding a pony, his dog running alongside.

Sims’s Mt. Meigs Home

In December 1836, he married Theresa Jones, also from Lancaster and the daughter of the wealthy widow of a local doctor, with whom he had nine children. After their marriage, the couple moved to Mt. Meigs, in Montgomery County, where Sims continued his practice for the plantation owners. In 1841, after suffering bouts of malaria and intestinal disorders, he moved his practice into Montgomery, trading in his pony for a four-wheeled cart with a horse and driver. By 1850, Sims’s practice was very successful, and the family owned 17 slaves, a house, and a building for treating patients. During this period, Theresa Sims’s mother and brother and Sims’s father and sisters relocated to Montgomery as well.

Sims’s Mt. Meigs Home

In December 1836, he married Theresa Jones, also from Lancaster and the daughter of the wealthy widow of a local doctor, with whom he had nine children. After their marriage, the couple moved to Mt. Meigs, in Montgomery County, where Sims continued his practice for the plantation owners. In 1841, after suffering bouts of malaria and intestinal disorders, he moved his practice into Montgomery, trading in his pony for a four-wheeled cart with a horse and driver. By 1850, Sims’s practice was very successful, and the family owned 17 slaves, a house, and a building for treating patients. During this period, Theresa Sims’s mother and brother and Sims’s father and sisters relocated to Montgomery as well.

In Montgomery, Sims developed his surgical expertise as well as techniques for treating cleft palate. Sims also began his career as a path-breaking and controversial figure in gynecology in Montgomery with his treatment of enslaved women suffering from vesico-vaginal fistulae (VVF) and recto-vaginal fistulae (RVF), which are tears that occur between the vagina and the bladder and less often between the vagina and the rectum as a result of prolonged labor. The condition remains prevalent among poor women in many societies today, and sufferers are usually left incontinent and are often shunned by society.

Under the authority of three local plantation masters, Sims performed experimental surgeries primarily on three enslaved women, Lucy, Betsey, and Anarcha, as well as various others, during the course of nearly four years. Anarcha, for example, had given birth at 17 after laboring for three days. Sims used forceps to end the ordeal and found that she suffered from VVF in the aftermath. In 1849, after some 30 surgeries, all of which were performed without anesthesia, Sims claimed he had cured her.

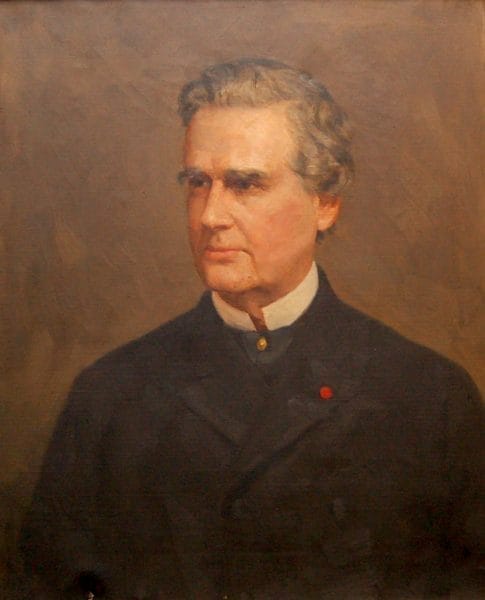

Sims’s Montgomery Office

Sims operated repeatedly without success on patients who had no say in the decision-making process that led up to their surgeries. He used opium to render them addicted and immobile. During the course of these and other surgeries on female patients, Sims developed a new type of speculum, which allowed him greater access to the areas most affected by VVF and VRF. This tool, called the Sims duck-billed speculum, is still in use today. Despite the controversy surrounding Sims’s methods, the medical innovations and techniques he developed during his Montgomery days, including the speculum, the Sims position (which allows greater visibility for the doctor) and the Sims sigmoid catheter, revolutionized the new field of gynecology.

Sims’s Montgomery Office

Sims operated repeatedly without success on patients who had no say in the decision-making process that led up to their surgeries. He used opium to render them addicted and immobile. During the course of these and other surgeries on female patients, Sims developed a new type of speculum, which allowed him greater access to the areas most affected by VVF and VRF. This tool, called the Sims duck-billed speculum, is still in use today. Despite the controversy surrounding Sims’s methods, the medical innovations and techniques he developed during his Montgomery days, including the speculum, the Sims position (which allows greater visibility for the doctor) and the Sims sigmoid catheter, revolutionized the new field of gynecology.

Sims often suffered from bouts of malaria and other maladies, and in the early 1850s he visited Philadelphia and New York City in search of a healthier climate. His interactions with other doctors in those cities helped to build his reputation, as they learned and began to use his tools and techniques. In 1852, Sims published an article about his VVF surgery and soon after became head surgeon at the Woman’s Hospital of the State of New York, founded to treat the condition.

At the onset of the Civil War in 1861, Sims left the United States and settled in Paris. He became internationally famous after ministering to European royalty, including the empress of Austria. After the end of the Civil War, he returned to the United States for a permanent residence. After a conflict with the hospital administration, Sims resigned from the Woman’s Hospital of New York State in 1874 and maintained a successful private practice. In 1876, he was named president of the American Medical Association. He composed his memoirs, The Story of My Life, in 1883 just before his death.

Today, there is considerable debate about the ethics of his surgeries. His innovations stand as a lasting contribution to medicine, as many women continue to incur the labor-related injuries suffered by Sims’s patients. Generally, however, scholars and other researchers consider Sims’s methods unethical, and indeed some have compared his experiments with those conducted during the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and in Nazi Germany. In 2018, in response to the controversy over his methods, the City of New York moved a statue of Sims from Central Park to Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, where he is buried. In 2021, the city of Montgomery unveiled a monument to the three women who suffered under his experiments entitled Mothers of Gynecology by artist Michelle Browder. The three sculptures of the women were created from discarded metal objects to symbolize how Black women have been treated and to demonstrate the beauty in the broken and discarded. It is located at 17 Mildred Street near the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

Further Reading

- Bankole, Katherine. Slavery and Medicine. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis, 2019.

- Owen, Deirdre Cooper. Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology. Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 2017.

- Sartin, Jeffrey S. “J. Marion Sims, the Father of Gynecology: Hero or Villain,” Southern Medical Journal 97 (May 2004): 500-504.

- Sims, J. Marion. The Story of My Life. Ed. H. Marion-Sims. New York: D. Appleton, 1886.