Cherokees in Alabama

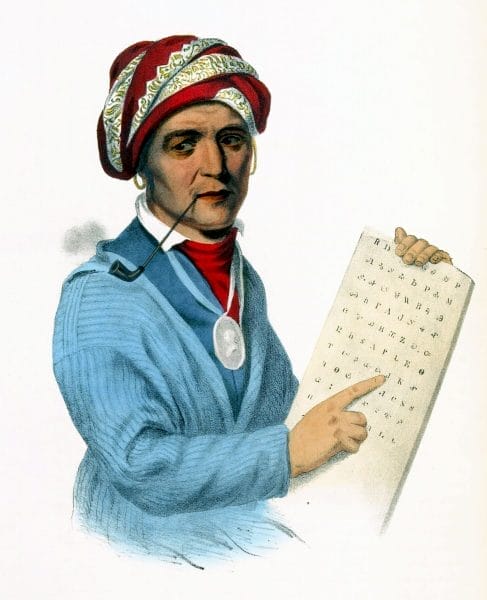

Sequoyah

Alabama became part of the Cherokee homeland only in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Nevertheless, this population of Native Americans significantly contributed to the shaping of the state’s history. Their presence in Alabama resulted from a declaration of war against encroaching white settlers during the American Revolution era. A few decades later, the Cherokees served as valuable allies of the United States during the Creek War of 1813-14. Although the Cherokees fought alongside the United States under Gen. Andrew Jackson, he later campaigned for their removal from the Southeast. Land hunger among whites led to the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which in 1838 resulted in the forced removal of the Cherokees to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River.

Sequoyah

Alabama became part of the Cherokee homeland only in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Nevertheless, this population of Native Americans significantly contributed to the shaping of the state’s history. Their presence in Alabama resulted from a declaration of war against encroaching white settlers during the American Revolution era. A few decades later, the Cherokees served as valuable allies of the United States during the Creek War of 1813-14. Although the Cherokees fought alongside the United States under Gen. Andrew Jackson, he later campaigned for their removal from the Southeast. Land hunger among whites led to the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which in 1838 resulted in the forced removal of the Cherokees to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River.

Cherokee settlements had historically occupied the fertile river valleys of the southern Appalachian Mountains in present-day northwest South Carolina, western North Carolina, east Tennessee, and north Georgia. Mountains separated these towns into three distinct regions: the Lower Towns, the Middle and Valley Towns, and the Upper or Overhill Towns. Their traditional hunting territory encompassed parts of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia. The effects of war and subsequent land cessions forced the Lower Towns to resettle north and westward during the era of the American Revolution. By 1782, the Cherokees had begun to establish settlements in what is now northeast Alabama in present-day Madison, Jackson, Marshall, DeKalb, Cherokee, and Etowah Counties and even as far west as Colbert County.

Three Cherokee Chiefs, 1762

During the war, the Chickamauga, a pro-British faction of Cherokees, split from the Upper Towns on the Little Tennessee and Hiwassee Rivers in east Tennessee. Led by war chief Dragging Canoe and supported by British agents and sympathetic traders, the Chickamauga left to establish towns farther down the Tennessee River. Two of these, Long Island Town and Crow Town, were located on the river near present-day Bridgeport, Jackson County. Nickajack and Running Water were just upriver near South Pittsburg, Tennessee, not far from Lookout Mountain Town in the extreme northwest corner of Georgia. From these Five Lower Towns, the Chickamauga launched raids on American backcountry settlements from middle Tennessee to southwestern Virginia. In 1792, Dragging Canoe died and his nephew John Watts became the leading war chief. Two years later, Tennessee militia leader James Ore launched a military expedition to punish the Chickamauga for their raids. The assault was devastating and resulted in the Cherokees suing for peace with the United States.

Three Cherokee Chiefs, 1762

During the war, the Chickamauga, a pro-British faction of Cherokees, split from the Upper Towns on the Little Tennessee and Hiwassee Rivers in east Tennessee. Led by war chief Dragging Canoe and supported by British agents and sympathetic traders, the Chickamauga left to establish towns farther down the Tennessee River. Two of these, Long Island Town and Crow Town, were located on the river near present-day Bridgeport, Jackson County. Nickajack and Running Water were just upriver near South Pittsburg, Tennessee, not far from Lookout Mountain Town in the extreme northwest corner of Georgia. From these Five Lower Towns, the Chickamauga launched raids on American backcountry settlements from middle Tennessee to southwestern Virginia. In 1792, Dragging Canoe died and his nephew John Watts became the leading war chief. Two years later, Tennessee militia leader James Ore launched a military expedition to punish the Chickamauga for their raids. The assault was devastating and resulted in the Cherokees suing for peace with the United States.

Cherokee Communities

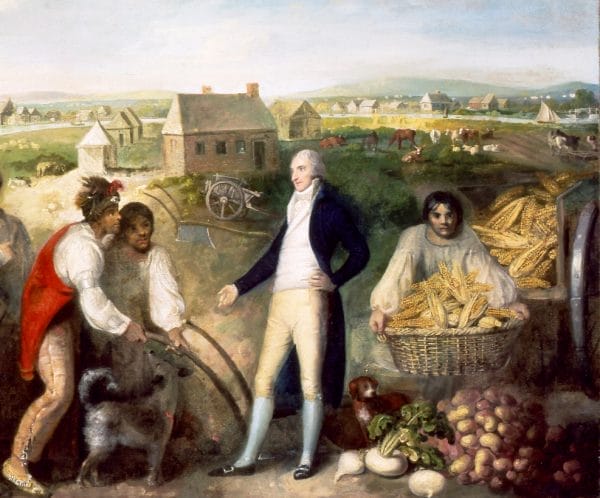

Benjamin Hawkins and the Creek Indians

By 1800 many Cherokees lived on dispersed farmsteads in northeast Alabama. They established communities at Turkey Town, Wills Town, Sauta, Brooms Town, and Creek Path at Gunter’s Landing, all of which provided leadership within the Cherokee Nation. Several of the towns served as sites of tribal councils. With the encouragement of the U.S. government, Christian missionaries established schools at Creek Path (1820) and Wills Town (1823). As part of the U.S. plan of civilization (formalized with regard to the Cherokees by the 1791 Treaty of Holston), the federally appointed agent to the Cherokees provided looms, spinning wheels, and plows to encourage Cherokee women to take up domestic arts and Cherokee men to give up hunting for farming and herding. In 1806, as hunting declined among the Cherokees, the U.S. sought and won a land cession, significantly shrinking Cherokee land in Alabama by 1,602 square miles.

Benjamin Hawkins and the Creek Indians

By 1800 many Cherokees lived on dispersed farmsteads in northeast Alabama. They established communities at Turkey Town, Wills Town, Sauta, Brooms Town, and Creek Path at Gunter’s Landing, all of which provided leadership within the Cherokee Nation. Several of the towns served as sites of tribal councils. With the encouragement of the U.S. government, Christian missionaries established schools at Creek Path (1820) and Wills Town (1823). As part of the U.S. plan of civilization (formalized with regard to the Cherokees by the 1791 Treaty of Holston), the federally appointed agent to the Cherokees provided looms, spinning wheels, and plows to encourage Cherokee women to take up domestic arts and Cherokee men to give up hunting for farming and herding. In 1806, as hunting declined among the Cherokees, the U.S. sought and won a land cession, significantly shrinking Cherokee land in Alabama by 1,602 square miles.

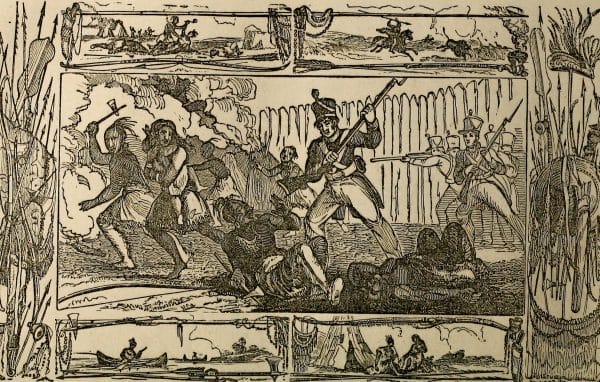

Battle of Tallushatchee

When war broke out in 1813, the Cherokees refused to join the faction of Creeks known as the Red Sticks, who were hostile to the United States. Instead, they fought alongside the Tennessee and U.S. troops under Andrew Jackson. Together they raided Creek villages along the Black Warrior River and fought in the November 1813 Battles of Tallushatchee and Talladega, from which they emerged victorious. Cherokee warriors played a major role in the attack on the Creeks of the Hillabee towns, who were members of the Red Stick faction. Following orders issued by Gen. John Cocke, the attacking party was unaware that the Hillabee had recently surrendered to Jackson. This one-sided assault became known as the Hillabee Massacre.

Battle of Tallushatchee

When war broke out in 1813, the Cherokees refused to join the faction of Creeks known as the Red Sticks, who were hostile to the United States. Instead, they fought alongside the Tennessee and U.S. troops under Andrew Jackson. Together they raided Creek villages along the Black Warrior River and fought in the November 1813 Battles of Tallushatchee and Talladega, from which they emerged victorious. Cherokee warriors played a major role in the attack on the Creeks of the Hillabee towns, who were members of the Red Stick faction. Following orders issued by Gen. John Cocke, the attacking party was unaware that the Hillabee had recently surrendered to Jackson. This one-sided assault became known as the Hillabee Massacre.

After American setbacks at the Battles of Emuckfaw and Enotachopco Creek in January 1814, the main Cherokee force joined Jackson for his assault on a large body of Red Sticks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend on the Tallapoosa River in east-central Alabama on March 27, 1814. Here the Cherokees crossed the river and created a rear diversion. This unplanned but successful action allowed Jackson’s troops to make a frontal assault over a formidable defensive log barricade and resulted in the killing of approximately 800 Red Sticks. This outcome decisively ended the war.

Although allied with the United States, the Cherokees suffered from the war as well. Some East Tennessee troops traveling through Cherokee territory destroyed property and terrorized families. Most of the damage occurred in the Sequatchie Valley and Wills Valley areas of present-day Alabama. It was not until 1817 that the U.S. government settled Cherokee claims amounting to $25,500.

Land Cessions

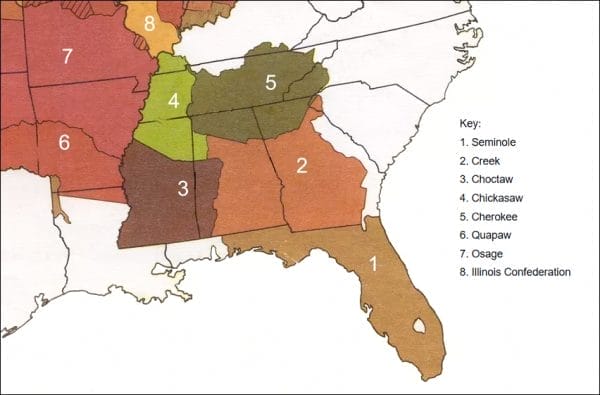

Indigenous Lands in Alabama

After the war, the U.S. government negotiated the Treaties of 1817 and 1819, which called for more Cherokee land cessions. Up to this time, the Chickasaw-Cherokee and the Cherokee-Creek boundary lines were not officially established. The United States paid the Chickasaws and the Cherokees, both allies during the late war, for lands north and south of the Tennessee River, as well as west of the Coosa River. Some Cherokees refused to leave their farms on ceded land and took advantage of a clause to claim private reserves. Most left their farms to relocate onto the shrinking tribal lands. Several hundred chose to journey across the Mississippi River to join the Old Settler Cherokees, a group that had emigrated prior to 1820.

Indigenous Lands in Alabama

After the war, the U.S. government negotiated the Treaties of 1817 and 1819, which called for more Cherokee land cessions. Up to this time, the Chickasaw-Cherokee and the Cherokee-Creek boundary lines were not officially established. The United States paid the Chickasaws and the Cherokees, both allies during the late war, for lands north and south of the Tennessee River, as well as west of the Coosa River. Some Cherokees refused to leave their farms on ceded land and took advantage of a clause to claim private reserves. Most left their farms to relocate onto the shrinking tribal lands. Several hundred chose to journey across the Mississippi River to join the Old Settler Cherokees, a group that had emigrated prior to 1820.

Another seminal event occurred after the war. Sequoyah, or George Guess, a veteran of the Creek War, lived in Wills Town (in present-day northeastern Alabama), where he developed a syllabary for writing the Cherokee language. In 1821, the Cherokee Council at Sauta approved its distribution to the people. The dissemination of Sequoyah’s syllabary transformed the Cherokee Nation into a literate populace within a few months.

Other prominent Cherokees lived in northeast Alabama. Cherokee siblings David and Catherine Brown became Christian converts at Wills Town Mission. David became one of the first Cherokee-speaking ministers, and Catherine became a mission schoolteacher. Double Head, a notorious Chickamauga warrior and chief, was executed in 1807 for selling Cherokee land for private gain. His brother-in-law Tahlonteskee emigrated west shortly thereafter and became a leader among the Old Settler Cherokees. Path Killer of Turkey Town served as principal chief during the Creek War of 1813-14. George and John Lowry served as military officers in the war, and George later became second chief.

John Ross

Perhaps some of the best-known Cherokees from present-day Alabama were the Ross brothers, both Cherokee-Scots from Turkey Town and Wills Town. Andrew served as a Cherokee Supreme Court justice, and John became principal chief in 1827, a critical time in Cherokee history. In 1830, the federal government approved the Indian Removal Act, which required most eastern tribes to relinquish their lands and remove west to Indian Territory, now the state of Oklahoma. John Ross led the Cherokee Nation’s struggle to stay, taking the battle for sovereignty to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1832. Though the court ruled for the Cherokees, then-Pres. Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the decision and the forced removal of the Cherokees began in September 1838.

John Ross

Perhaps some of the best-known Cherokees from present-day Alabama were the Ross brothers, both Cherokee-Scots from Turkey Town and Wills Town. Andrew served as a Cherokee Supreme Court justice, and John became principal chief in 1827, a critical time in Cherokee history. In 1830, the federal government approved the Indian Removal Act, which required most eastern tribes to relinquish their lands and remove west to Indian Territory, now the state of Oklahoma. John Ross led the Cherokee Nation’s struggle to stay, taking the battle for sovereignty to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1832. Though the court ruled for the Cherokees, then-Pres. Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the decision and the forced removal of the Cherokees began in September 1838.

Fort Payne, DeKalb County served as one of 13 collection stockades and as one of five debarkment stations scattered throughout the Cherokee Nation and was the only one located in Alabama. From these places, 13 detachments of emigrants departed. Approximately 1,200 Cherokees marched over the John Benge Route, the north Alabama trail named for its Cherokee conductor, to join the mass exodus along the Trail of Tears to Indian Territory. Other Cherokees travelled via the water route down the Tennessee River to Decatur, Morgan County. Here they disembarked and travelled overland to Tuscumbia, Colbert County, to avoid the dangerous Muscle Shoals, and then boarded boats that took them on the rest of their journey.

Trail of Tears Commemorative Motorcycle Ride

The Cherokee presence is still very much a part of Alabama culture. Many citizens claim Cherokee ancestry, insisting that their forbearers escaped or hid to avoid removal. Annual events that honor Cherokee history include the Trail of Tears Commemorative Motorcycle Ride, which begins in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and ends in Waterloo, Lauderdale County, and the Cherokee River Homecoming Festival held in Moulton, Lawrence County, as well as locally sponsored pow-wows. The Alabama Indian Affairs Commission works with four Cherokee state-recognized groups, the Echota Cherokee Tribe of Alabama, the United Cherokee Ani-Yun-Wiya Nation, the Cherokee Tribe of Northeast Alabama, and the Cher-O-Creek Intratribal Indians, Inc. The federal government recognizes only three Cherokee groups: the Cherokee Nation, the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Nation, none of which are located in Alabama.

Trail of Tears Commemorative Motorcycle Ride

The Cherokee presence is still very much a part of Alabama culture. Many citizens claim Cherokee ancestry, insisting that their forbearers escaped or hid to avoid removal. Annual events that honor Cherokee history include the Trail of Tears Commemorative Motorcycle Ride, which begins in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and ends in Waterloo, Lauderdale County, and the Cherokee River Homecoming Festival held in Moulton, Lawrence County, as well as locally sponsored pow-wows. The Alabama Indian Affairs Commission works with four Cherokee state-recognized groups, the Echota Cherokee Tribe of Alabama, the United Cherokee Ani-Yun-Wiya Nation, the Cherokee Tribe of Northeast Alabama, and the Cher-O-Creek Intratribal Indians, Inc. The federal government recognizes only three Cherokee groups: the Cherokee Nation, the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Nation, none of which are located in Alabama.

Further Reading

- Bunn, Mike. Fourteenth Colony: The Forgotten Story of the Gulf South During America’s Revolutionary Era. Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2020.

- McLoughlin, William G. Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986.

- Mooney, James. History, Myths, and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokees. Asheville, N.C.: Historical Images, 1992.